Doug Halladay, one of Detroit’s great jazz creatives during the late 1960s and ’70s, was on vacation in Mexico with his wife Sandra in 2009 when he began feeling as if something had sapped the energy from his body.

Concerned — having never been seriously ill before — he cut his vacation short and went to his family doctor. His blood pressure was suspiciously low. After finishing the exam, his doctor admitted Halladay to Henry Ford Hospital where he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, a blood cancer that attacks the blood and bone marrow.

To stay alive, Halladay needed a bone marrow transplant. Acute myeloid leukemia was the cancer that killed the famed jazz saxophonist Michael Brecker in 2007 after a lengthy and unsuccessful search for a donor. Halladay was luckier. His search turned up Herman Eyr, a 25-year-old in Germany. The transplant was performed in May 2010. It beat back the cancer, but left Halladay partially blind in one eye.

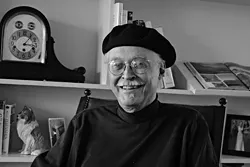

“Life takes on a different meaning when you come through something like that. I was so grateful to the doctors and the nurses at Henry Ford that I wanted to do something to give back,” Halladay, 69, said on a Sunday afternoon in late summer, sitting on the patio of the co-op he owns in Lafayette Park and petting his collie Sasha.

Halladay is a tall and a thin man who looks like a cross between a retired NBA forward and a college professor. After enjoying success in music, Halladay left the business in the 1970s to embark on several different career paths, including stints in educational television, school reform and health care reform.

On this particular afternoon, he talks about being a leukemia survivor, about his efforts to educate African-Americans, Arab-Americans and Hispanic-Americans about leukemia, and about how this relates to his return to jazz.

A study published in the Journal of the American Cancer Society in 2010, reported African-Americans are 40 percent less likely than whites to receive bone marrow transplants for blood cancer treatment, and they account for only 7 percent of the 8 million people registered with National Marrow Donor Program.

Halladay’s pianist friends Buddy Budson and Keith Vreeland convinced him to organize a benefit concert. The concert attracted a bunch of sponsors, including Henry Ford Health System. Twenty-five Detroit jazz musicians participated in the concert, which raised $20,000. Halladay put on two more concerts at the Kerrytown Concert House in Ann Arbor and the historic First Congregational Church in Detroit. Pianist Charles Boles, who arranged some music for the concerts, said the Detroit jazz musicians were eager to help Halladay because he’s a good man.

“I think first and foremost, the jazz musicians like him as a person, and they respect his ability as a composer. That’s why they were eager to help Doug,” Boles says. “A lot of times, people won’t help you if they don’t like you. They have to like you. I don’t care what caliber of musician you are. I think Doug is a fine man for what he’s doing, and he’s an excellent music writer. In spite of his illness, he has grown considerably as a composer.”

Halladay grew up in Grand Rapids. He’s a largely self-taught musician, although he took courses in music theory and harmony at Albion College. He played trumpet up and down the North Shore of Chicago with pianist Eddie Russ, later to be part of the popular Detroit group Mixed Bag. Russ also recorded with the great saxophonist Sonny Stitt.

“When Russ touched the piano, it was like a godsend. He was like the great jazz pianist Wynton Kelly. Eddie showed me a lot, and we played a lot of gigs. He was one of those unsung heroes who never got the right recognition. He died of kidney failure,” Halladay recalls.

In 1967, Halladay moved to Detroit and hooked up with jazz musicians, such as Kenny Cox, Charles Moore, Doug Hammond and James “Blood” Ulmer. Halladay bought a Victorian house on Lincoln Street, renting rooms to saxophonists Phil Lasley and Faruq Z. Bey. They formed the Lincoln Street Band with bassist John Dana, drummer Danny Spencer and pianist Keith Vreeland in the rhythm section.

Halladay quit playing in the early ’70s. Some of his musician friends begged him not to. “Honestly, I wasn’t a good trumpet player. I wanted to play at a certain level and I couldn’t do it. To play at a high level of creativity on the Detroit jazz scene, you had to be on the bandstand six nights a week doing it. I didn’t want to spend the weekends playing weddings and polka gigs, or doing what musicians have to do to make a living.”

He earned a graduate degree from Wayne State University, and later worked as the director of communications at Channel 56. “I had other interests outside of music,” he says. “I grew up in the ’60s. I was involved with the civil rights movement. I was a member of SNCC. I got a master’s degree in urban sociology and race relations. My wife and I bought a home in the city, and we’re involved with trying to improve the quality of life for people in Detroit. So, I’m proud of what I’ve done to try to make Detroit a better place. My music took a back seat to that.”

Halladay kept writing music, but it wasn’t performed publicly. That changed when he put on the benefit concerts. The first concert was recorded and released as bye the New Beginnings Ensemble. “Point of Interception,” the opener, has the rhythmic feel of and early Blue Note recording. Other compositions such as “Samba for Eddie” and “Only the Noze Knows,” show that he’s essentially a swing-conscious composer. The players sound as if they had an absolute ball playing his music and never wanted to stop.

Halladay never thought he’d be spending his days at home composing music — or having it played for a worthy cause. There are two more benefit shows coming up. First is Nov. 2, at Historic St. Matthew’s & St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church, underwritten by a grant from the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute. In December, at Kerrytown Concert House, a concert featuring arrangements by pianist Gary Schunk of some of Halladay’s Latin music is scheduled. Lately, he’s taken a stab at writing big band music.

“I’m alive, and I’m grateful to be here and do what I can do on this planet. I want to get the message out, particularly to minority people who are dying out here because they can’t find a match, whether it’s leukemia or other types of blood cancers,” Halladay says.

It just so happens that getting the word out also involves spreading some interesting music as well. And that benefits us all.

Doug Halladay’s New Beginnings Ensemble performs 4-5:30 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 3, at the Historic St. Matthew’s & St. Joseph’s Episcopal Church, 8850 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-871-4750; $15 in advance, $20 at the door.

Charles L. Latimer writes about jazz for Metro Times and blogs at idigjazz.blogspot.com. Send comments to [email protected].