Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe

by Kate Buford

Knopf, 496 pp., $35, hardcover

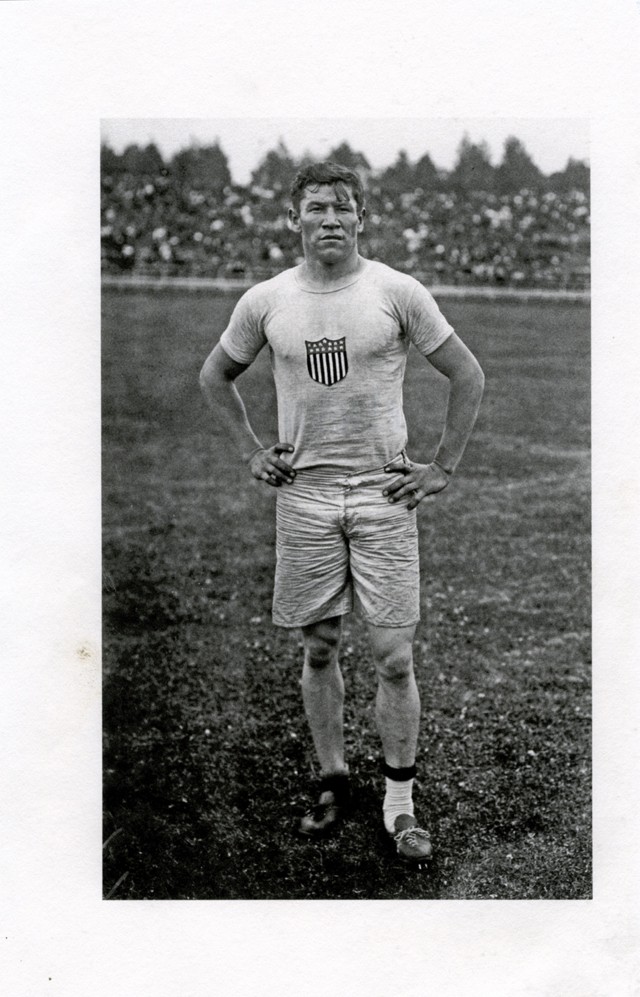

Few remember, but the name Jim Thorpe was once synonymous with athletic prowess. The all-star played football and baseball, won Olympic gold medals in 1912 and was, in many ways, the first sports superstar. A Native American of the Sac and Fox, he was embraced by the sporting public as both an American and as an aboriginal. And his meteoric rise was only equaled by his dismal fall. Kate Buford chronicles it all, working hard to separate the mythology (there is much) from the fact in this sprawling biography.

Football fans will likely find Buford's description of football 100 years ago eye-opening. The contests were tough and dangerous then, making the controversy over today's "helmet hits" look quaint by comparison. In 1904, more than 200 players were injured, and 21 were killed in the game. Officials belatedly took action, changing the rules after the 1909 season, in which 36 fatalities were recorded.

Thorpe's athletic rise coincided with the rise of team sports that would later dominate the 20th century. Buford argues that it dovetailed neatly with the disappearance of the frontier, and an effort to re-create through competition the energy of the pioneer in the age of Teddy Roosevelt's "strenuous life." War metaphors abounded. Baseball was the "bloodless battle." Football was a ritualized conflict.

Of course, it wasn't lost on spectators that Indians (Buford uses the terminology of the day to keep the narrative brisk) were now fighting the white man on the field, and often winning.

Don't blame the Indians: The WASPs had created that metaphor in the first place. As early as 1896, Henry Cabot Lodge, speaking in the spirit of Anglo-Saxon chauvinism that marked the day, declared the "injuries incurred on the [football] playing field" to be "the price which the English-speaking race has paid for being world-conquerors."

But Lodge and company hadn't counted on Thorpe and the Indian footballers of Carlisle University, a school exclusively for Native Americans.

Stories abound about the discovery of Thorpe's skill at college. Buford finds at least one reliable account: When Thorpe applied for the Carlisle football team in 1907, Coach "Pop" Warner handed him the ball as a joke and told him to run through the dozen defenders as "tackle practice." Thorpe ran, dodged and swiveled his way through the defense. An angry Warner cried," You're supposed to let them tackle you, Jim!"

"Nobody is going to tackle Jim," Thorpe declared. He made the team.

Under Warner's leadership, sports fans were treated to matches rich in national metaphor: an Indian team stepping onto the gridiron less than 20 years after Wounded Knee. When Carlisle defeated rival University of Pennsylvania, one newspaper remarked, "With racial savagery and ferocity, the Carlisle Indian eleven grabbed Penn's football scalp and dragged their victim up and down Franklin Field."

Buford quotes Thorpe as later saying that "the descendents of the losing race came into the east" and played football against the descendents of their conquerors "with the same ... fierceness of their ancestors."

When Carlisle beat St. Louis University 76 years after the defeat of Black Hawk in that city, a St. Louis editorial writer remarked, "It was St. Louis that made the head men of the Sac and Fox nation drunk and induced them in this condition to sign away the tribal lands. ... Mr. Thorpe humiliated us nicely, which was just as it should have been. It was coming to us."

Sometimes, the metaphor of these early football games strains credibility. In a 1912 match, Carlisle went to West Point to play the Army team and won 27-6, whipping a team that included four future World War II generals (among them Dwight D. Eisenhower) and future first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Omar Bradley.

Thorpe became a national hero when he triumphed at the 1912 Olympics, winning gold in the decathlon with a score that remained unbeaten for decades. But when it was discovered that he'd played a few seasons of professional baseball, Olympic hardliners took away his medals. Thorpe later said, "I went to play baseball in North Carolina for a couple of summers and paid for it for the rest of my life."

Buford carefully chronicles Thorpe's long fall, his increasingly desultory career, his drunken antics, his failed marriages, his descent into manual labor. At one point, Thorpe wound up in Detroit, working security for Ford Service head Harry Bennett, who'd assembled a rogue's gallery of former athletes, often troubled ones, to break union skulls if need be.

After getting suckered into a marriage with a huckster who tried to sell him like shoeshine, Thorpe retreated increasingly to alcohol, unable to hold down jobs. Even in death, the myth was much kinder to him than the truth: He lay dead and alone at 65 of coronary sclerosis in his trailer in Lomita, Calif. It was a sad ending, but as we approach the centennial of his Olympic triumph, now is a good time to take stock of America's first international sports hero.