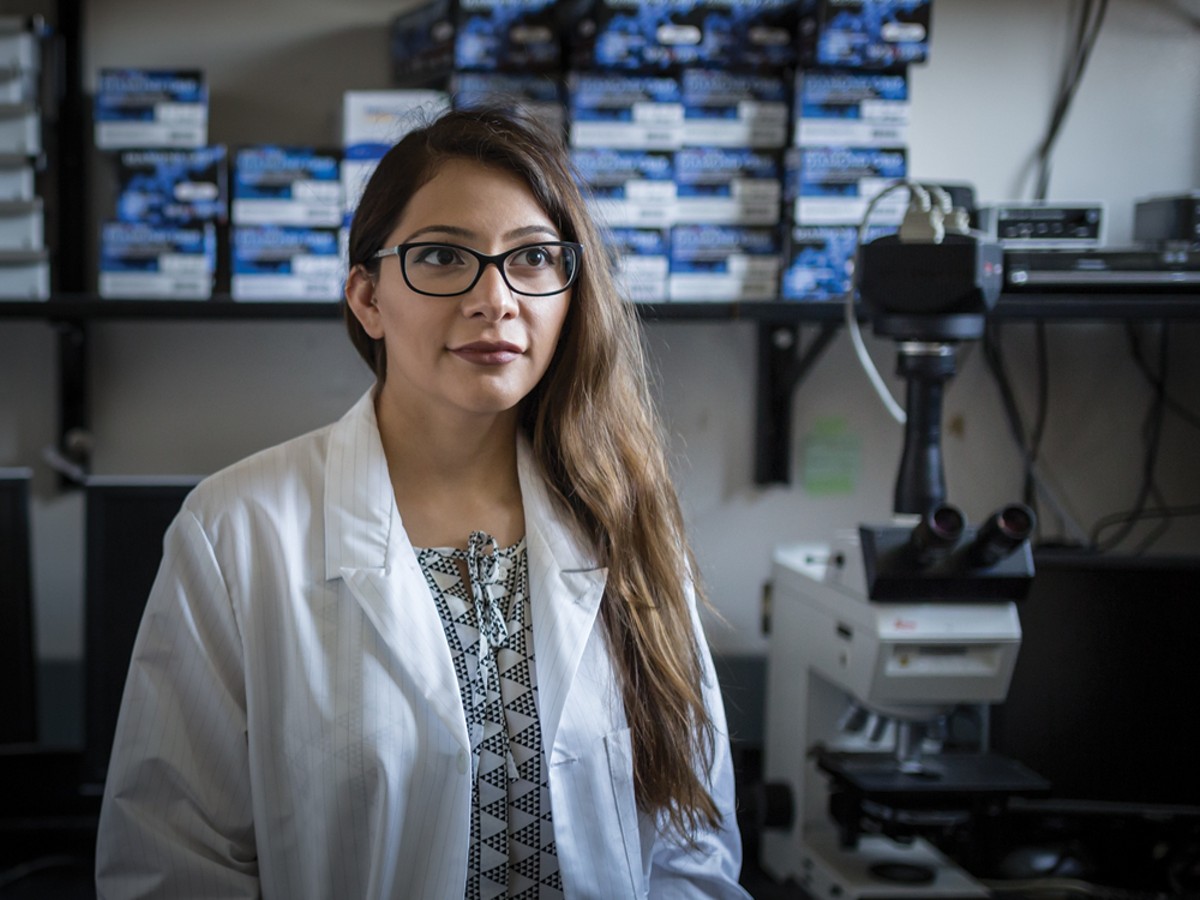

Raised in California and Arizona by Mexican migrant workers, Natalie Nevarez isn't really a Detroiter. She's a Ph.D. student at the University of Michigan, where she recently defended a dissertation paper based on her research of monogamy in prairie voles, and soon she's moving to California where she'll continue her neuroscientific study of the mammal at Stanford University.

While conducting her research at U-M, Nevarez's friends started joking about a $25,000 scholarship being offered to women studying science, technology, engineering, and math by online pornography giant PornHub. But Nevarez didn't find it funny. She applied for the money — and won.

While the controversial scholarship is an interesting anecdote, it seems like a minute detail if you know Nevarez's whole story.

When she was 7 years old, her mother decided to get her GED, yet she faced a seemingly insurmountable obstacle: She spoke only Spanish. Nevarez had taught herself English by watching cartoons and listening to Tupac, so she became her mother's translator, helping her earn a diploma.

By 13, Nevarez enrolled herself in community college. She'd been helping her mother take courses there and figured she might as well get some credits herself. She completed her associate's degree by 16 and walked in her college graduation before even completing high school, as crazy as that sounds. She graduated from high school at 17, after spending her entire senior year doing a photography independent study, a move she calls "stupid."

After earning her undergraduate degree in Arizona, she was accepted into U-M, although she admits at that point, she didn't really know where Michigan was. She'd been so busy gobbling up neuroscience classes, she hadn't taken the time to learn basic subjects, like geography.

"Just being honest, my education wasn't very good," Nevarez says. "For the most part, the school really struggled with kids not speaking English, so most of my day I spent as a T.A. helping teachers with students who weren't English-speakers. I was so behind on so many school topics, but I really liked neuroscience, so I kind of put all my eggs in one basket and I became very knowledgable in one subject while not being caught on all these other really basic things."

Now, Nevarez studies topics like geography, philosophy, and history in her spare time, creating her own curriculum in order to catch up — which is, if nothing else, a testament to her love of learning.

Throughout her childhood, her parents emphasized the importance of education, but she says they never really needed to say a word. Seeing them physically exhausted at the end of a work day was enough.

"They both really always told us that an education was something no one could ever take from you," Nevarez says.

Nevarez's parents separated when she was 13 and a few years later, her father was deported. He's still a migrant farmer, but now makes a fraction of the pay.

"It sucks because he is literally doing the exact same job, but for way less money. As if the job wasn't hard enough," she says.

Nevarez says she often feels pangs of guilt for not pursuing a field that would directly advance brown people — a field like city planning, which her sister is currently seeking a Ph.D. in.

"That's one thing that comes with being a brown girl in academia," Nevarez says. "Sometimes I feel guilty that a lot of people who are minorities in grad school tend to study minority issues. Obviously that is super important, so sometimes I feel a little guilty that I am studying, you know, monogamy, which isn't necessarily a brown people issue."

Regardless, Nevarez has still found ways to help marginalized communities. She started a student organization called MYELIN, a group that mentors children from low income and minority families by offering free science-based workshops. She hopes to inspire a new generation of brown kids to love neuroscience as much as she does.

"An education is your ticket out," Nevarez says.

Back to the People Issue.