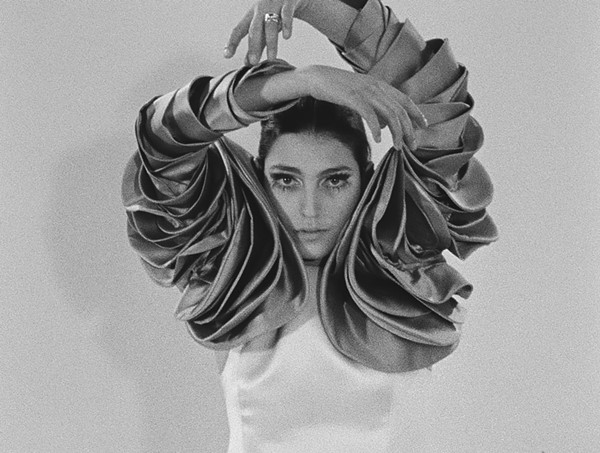

In the 1960s, Benedetta Barzini was photographed by Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, a muse to Salvador Dalí and Andy Warhol, and the first Italian model on the cover of American Vogue. But in the 1970s, she stepped away from the fashion industry and became a Marxist and spokeswoman for the Italian women's liberation movement.

This year, her son Beniamino Barrese released The Disappearance of My Mother, a documentary about Barzini's extraordinary life. The film touches upon her legacy in the fashion industry (the 76-year-old still models) and her transition to feminist and professor. However, the main focus of the documentary is the opposing objectives of both mother and son. While Beniamino desires to capture his mother on film and keep her close, Barzini has contempt for any lens and desires to leave everything behind and vanish.

Metro Times interviewed Barrese about the film, his relationship with his mother, and her reactions to seeing herself on screen.

Metro Times: What were your first memories of your mother?

Beniamino Barrese: I remember when she was working at night. She always had a second life at night, where she was writing, reading, and listening to the news. When I woke up at night, I would go in secret into the kitchen, I would find her working on the table in the kitchen and I could see her back.

MT: When did you realize that she was a notable figure in history, especially in the fashion industry?

Barrese: When I was born, she was 42. As I grew up, I figured out that she had a lot of lives. I understood from other people that my mom was on TV and I didn't know why she was on TV. When I was little, I found this portfolio of photographs of her with a few of her covers from Vogue and Harper's Bazaar. That's when I understood that she was also a young person. She was clearly different and was a model. She didn't like to talk about it, but I would ask her about it.

MT: And she didn't have any of her photographs hanging up from her modeling career?

Barrese: No, not really. She wasn't proud of that. She occasionally had a few photos of her with other people, but they were more contemporary photos. There is a beautiful black-and-white portrait of her with my brother taken by Richard Avedon. So when I visited her, I would always look at this picture that hung very high on the wall. I would be like, "That picture is amazing. Who's that photographer?" And she would talk to me about Avedon. But yeah, nothing from her fashion years so much.

Instead of pictures of her, I remember there was this big painting of Karl Marx and next to a big Coca-Cola sign that she got from New York. And that was like the two extremes of her life.

MT: What do you think the Coca-Cola sign stood for?

Barrese: This pop culture that she kind of sucked in, this '60s in New York. I think as much as she rejected it, she was also, you know, she was also taken by it.

MT: How has your mother changed over the years since you were a child? Was she always the way she's perceived in the film?

Barrese: In the film, I made it look a lot more gray and black, but in reality, she's a lot more colorful and sweet and funny. In telling a story, you have to convey a specific view and simplify a lot compared to real life. She's more complex. Before, she was much more social ... she's always been going against standards.

She's been a very good mother. She was beautiful — and she worked, thanks to her beauty. At the same time, she always criticized that. This is one thing that I learned more about her. I think a valuable lesson is that you have not much space for choice. You always have space for thinking with whatever life brings you. For her, it was modeling. It's not about saying no because you have principles, necessarily. It's about doing it and using that as a method for thinking, building, and developing a point of view. Now she wants to go disappear. She always talked about that, but she never really did it.

MT: In the documentary, it shows that your mom is still working in the fashion industry. Has she talked to you about how she feels about that?

Barrese: I understand 100% why she does it. From my point of view, and she says [this] often, is that being beautiful is not a talent. Being a model is a job. Somebody uses you for a specific time for something. I feel like she has a massive talent, which is a charisma that comes through that has nothing to do with being pretty. It's like a good actress. We can only work with whatever we have. She has different talents, but obviously beauty shines more and maybe is more appreciated, especially for women.

Also, if she gets the chance to show a different kind of woman on a catwalk or in a photograph, this could be empowering. She has let time kind of leave its marks and hasn't changed her appearance to fit into some standard.

MT: Do you live near your mother?

Barrese: I moved back to Italy, but I don't live with her because she doesn't really have a house anymore. She has a space that used to be her office. There's kind of like a bed that's not even really a bed. A bathroom that's not really a bathroom. There's no kitchen. It's a little bit extreme.

MT: Is it hard for you to see your mother live that way?

Barrese: I would love for her to live better. I hope that I'll be able to help her to have a better place to live in, but at the same time I feel she had such a wealthy, luxurious life as a child. She came from this very rich family, but she was missing the most important thing, which was love, care, and affection.

MT: How would you describe your relationship now?

Barrese: I think it's a lot more balanced because I'm a very sensitive person, and she is a powerful person, but very sensitive. I'm super influenced by her. There is pain under her charisma. So the fact that I could look at her for so long and up close and then put out a portrait of her really helped me to separate myself.

MT: What does your mother think of the documentary?

Barrese: She thinks that it's a work of love. She sees the work put into it and appreciates it. She never told me that she thinks this is a good film, but she doesn't really like cinema that much.

When she saw it the first time, she told me this is not me. But now she says that, actually, this is her. Although it's painful for her to be in front of the camera and to see herself onscreen, she's grateful. She understands how other people are moved and inspired by seeing a woman living differently and with the courage to accept her body and life. We brought this to festivals, and sometimes she came with me. People were very excited and inspired. They would be like, "Oh, my God, you say the things I agree with, but I don't have the courage to say these things." It's been very powerful and revitalizing for her.

The Disappearance of My Mother will be screened from Thursday, Jan. 16 through Sunday, Jan. 19. at The Film Lab, 3105 Holbrook Ave. in Hamtramck; thefilmlab.org.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.