Despite the raucous, emotional, and thoroughly engaged crowd at Flint's Whiting Auditorium, the muckraking master polemicist and hometown hero Michael Moore looks a little tired.

He's tired of being right all the time, of constantly breaking ground and then watching that soil slowly erode beneath him. He's tired from the endless crusade he's waged since the mid-'80s, railing against the ever-expanding fusion of corporate and political power, and the concentrated effort by the ruling class to strangle, stifle, and erase poor and working class people in this country — to deny them a voice, a choice, or even the belief that they can ever affect the direction of their own lives. Moore is also apparently too tired to talk to the media, slipping past the assembled gaggle of local journalists waiting in vain, huddled under a concrete awning, dodging drizzle.

Moore has returned to Flint for a special preview screening of his latest film, Fahrenheit 11/9, and when he finally takes the stage, he seems to find the energy needed to fire up the room with his trademark flair for the melodramatic. "This could be our last film," he says. "There's a process that has started to take our democracy away from us, to nip at it, to whack away at it until you wonder, 'Where is this going?' I said that we had to make this film like we're in the French Resistance, but now the tanks are 20 miles outside of Flint."

Since his breakthrough film debut Roger and Me in 1989, Moore has seen the multiple economic and ecological disasters that have befallen Flint as intentionally inflicted plagues directed at a once-prosperous automotive manufacturing town that played a major role in the growth of the labor movement and the expansion of the middle class. Later, as a majority African-American city, he says, it became an easy target for neglect and political abuse.

"This movie is how I think we got here, how Flint and Governor [Rick] Snyder was the coming attraction for the rest of the United States of America," he tells the audience. "We saw the elimination of democracy here first through the emergency manager laws, as did Detroit and Pontiac and Benton Harbor. You could've predicted everything about Trump if you'd paid any attention to us here in Flint."

The film itself, which the trailers paint as a full-on assault on Trump, instead picks multiple targets responsible for all of the USA 2018's problems, including but not limited to: CNN, NBC, the DNC, the GOP, the NRA, Matt Lauer, Snyder, Nancy Pelosi, Steny Hoyer, Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and even Gwen Stefani. Yes, the "Hollaback Girl" herself.

In Moore's telling of the story, the clumsily staged announcement of Trump's presidential run was a publicity stunt, using paid actors posing as grassroots supporters, serving as a stealth protest against NBC for giving Stefani a bigger contract to judge a singing contest than Trump was pulling down for his reality game show The Celebrity Apprentice.

At first, no one in the establishment took Trump seriously. The Sunday talk show panels could barely suppress their giggles at the very notion of the Cheetos-hued interloper. Then something really funny happened: The major networks caught Trump fever. Whenever the perpetually failing real estate mogul started rambling, bragging, and blurting casual racist dog whistles into an open mic, people tuned in and profits rose.

After a brilliant opening sequence that details the slow unfolding horror of election night 2016 — the confusion and shock of Clinton supporters, the pundit class, and the old guard in Washington — Moore doubles down on the Trump bashing, but at this point there's not much stuffing left in this punching bag. Trump's vanity, his churlishness, his greed, his utter void of intellectual curiosity — these are the exact same weak spots that get jabbed every night by a chorus of late night comedians.Trump's personal ethical swamp is so disgusting and toxic that it's almost a relief when the movie pivots to the much cleaner topic of the Flint Water crisis. At least in the horrific, ongoing, slow-motion tragedy of the poisoning of Flint there are heroes to be found.

‘You could’ve predicted everything about Trump if you’d paid any attention to us here in Flint.’

tweet this

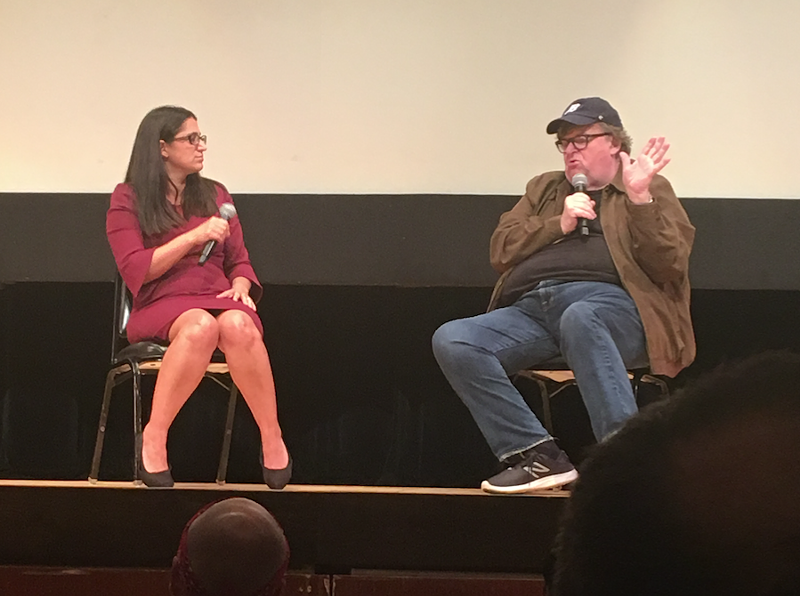

Perhaps the best example is the noble Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, daughter of Iraqi immigrants who fled from Saddam Hussein, a graduate of Royal Oak's Kimball High School, and the pediatrician who was the first to discover and blow the whistle on the dangerously high levels of lead being found in Flint children's blood. Dr. Mona is prominently featured in the film, and takes to the stage with Moore afterward for a spirited Q&A session.

While her research and reporting of the crisis made her an accidental activist, Hanna-Attisha has abundant intelligence and poise, which makes her especially suited for the task. She feels anyone can leverage their resources, experience, and skills for positive change.

Hanna-Attisha says the message of both the film and her recent book, What the Eyes Don't See, is that "we are all powerful people."

"We all have the ability to open our eyes, to not accept the status quo, and to be active and to fight for a better tomorrow," she says. "So that's the situation I found myself in, but that's the story we're finding all over. It's a story of activism and of resistance. People are saying, 'That's enough.' We want to make a difference in the lives of our families and our communities."

As Dr. Hanna-Attisha cheerfully asserts, this is all possible with effort. "Anybody can do this. You do not need to be a doctor," she says. "Anyone, anywhere, no matter how long you've been in this country, all have the power within us to make the world better."

Hanna-Attisha seems always able to hit such grace notes, to find ways to empower and encourage change in a resilient but hopeful way, but Moore seems inclined to nurture his darker, more apocalyptic instincts. Onscreen he's still prone to theatricality and stunts, like hosing down Snyder's posh front lawn with a tanker truck full of contaminated Flint tap water, or waltzing into the state capital with a pair of handcuffs to make a citizen's arrest. On stage, with a supportive crowd, he seems eager to push even further.

"The only way there will be justice is if there is an uprising," he says, pensively pausing for a few beats. "Non-violently, of course." With his voice faintly quivering, Moore briefly struggles for the right words, cannily noting that there's "press here and this can get chopped up."

Uncharacteristically, he's hesitating to say what he really feels. Stressing his personal pacifism, he finally allows himself to wonder aloud why the people of Flint never openly revolted. On cue, the good doctor gracefully delivers an answer about the city's resilience, its strength and hopefulness, and about conquering anger. It's the perfect, polished, and optimistic response. Moore, the career-long snarky prankster, offers a more interesting answer about his motivation to keep fighting.

"I got out," he says. "I was living here drawing $98 a week [in] unemployment one week before Roger and Me was shown in a movie theater. I drew the golden ticket, the lucky card. I and 100,000 others got out. I think that there's a certain amount of survivor's guilt in me, and those that had the means and the wherewithal to get out, who had the relatives who helped them get out. I didn't show this in the movie; the people who drive to relatives in Lansing or Detroit, drive 60 miles away just to take a shower. In a city sitting in the middle [of] the largest freshwater source on Earth."

When Moore frets that Trump will be ‘the last president of the United States’ you can tell he's not kidding.

tweet this

While he admits he did not personally suffer, the outrage of what was done to Flint, and the daily outrages done to the country as a whole have worn on him, forcing him to change his approach.

"I think people at the Toronto Film Festival the other night, and some of the press, were expecting to come in and see Mike being the jokester and having fun with Trump. I'm not laughing. There's nothing funny about any of this," he says. "I'm one of the few on our side of the political fence that took [Trump] seriously from day one," he says. (Moore predicted in July 2016 that Trump would win, and believes he could win re-election in 2020.)

"I never thought he was funny. I thought he was a genius," Moore says. "I thought he's one of the best performance artists ever. And that his evil genius was to outsmart maybe the smartest person ever to run for president, He was able to outsmart the Democratic party. He totally destroyed one party, and the other party said, 'No, no, you don't have to destroy us. Like Vichy France, we'll go ahead and destroy ourselves.'" When Moore frets that Trump will be "the last president of the United States" you can tell he's not kidding.

Fahrenheit 11/9 also assigns plenty of blame for this daily freak show to the mainstream Democratic politicians too willing to compromise. Sure, there's a bit of goofing around about HRC's awkward dancing, her forced gaiety and cozying up to hip-hop stars for votes, but behind it is real, pointed ire at the DNC effort to rig the primaries for their chosen candidate and away from the uprising of Bernie Sanders. Even harsher, and more surprising, is Moore's condemnation of Obama for flying into Flint in 2016 and callously making a big show of drinking the contaminated tap water during a press event, a move that was misguided at best and cynical at worst. The energetic crowd, which laughs and shouts back at the screen throughout the night, grows eerily quiet during the Obama portion, as if this was one betrayal too many. In a place where state and local government had failed them so often, it is a reminder that even the president they loved came up short when needed most.

There are slivers of hope peeking through the dark clouds, namely the growing numbers of "extraordinary ordinary people" that are mounting a resistance. There is a long segment in the film devoted to the recent statewide teachers' strike in West Virginia, which proved successful, and has inspired walkouts nationwide. There is the influx of newly energized and openly progressive candidates, mostly women, like Detroit's own Rashida Tlaib who are positioned to storm Congress in the fall. There's enough in this thread to weave a whole movie, and in happier times, the filmmaker might have pursued this angle.

Yet Moore doesn't allow himself or the audience to linger in hope. He wants action, and, just maybe, he knows that gloom and doom is an easier sell.

It's quite possible to read Fahrenheit 11/9 as Moore's valedictory address, a summation of all the issues he's tackled over 30-plus years as a progressive flame thrower: the dismantling of labor unions, racism, government corruption, crony capitalism, media distortion, health care, gun violence. However, for a change, the tone is not smug or self-congratulatory, but alarmist. Despite his repeated warnings and mockery, these social nightmares haven't gone away, and in many cases have only gotten worse.

It's impossible to watch Moore hanging out with David Hogg and the rest of the brave Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School massacre victims-turned-activists, and not think back to Moore's 2002 film Bowling for Columbine, which tackled mass shootings and gun violence. How many lives have been senselessly lost since then? How many more will be lost before something changes?

Moore isn't willing to wait any longer — and we shouldn't, either.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.