The MC5's is a story that has entered into rock 'n' roll folklore, not only in Detroit but internationally. Yet so much about the band is either forgotten or shrouded in secrecy. We know about promoter Russ Gibb making them the house band at his famed Grande Ballroom. We know about the connection with John Sinclair and, in turn, the White Panthers and Trans-Love Energies, political manifesto and all. We get to still look at the iconic poster art of Gary Grimshaw and Carl Lundgren, and the photographs of Leni Sinclair. We mourn Rob Tyner, Fred "Sonic" Smith, and Michael Davis, while enjoying the fact that their music with Wayne Kramer and Dennis "Machine Gun" Thompson lives forever thanks to the Kick Out the Jams, Back in the USA and High Time albums. But the MC5's fire burned so bright and briefly that it was almost over before it really got going.

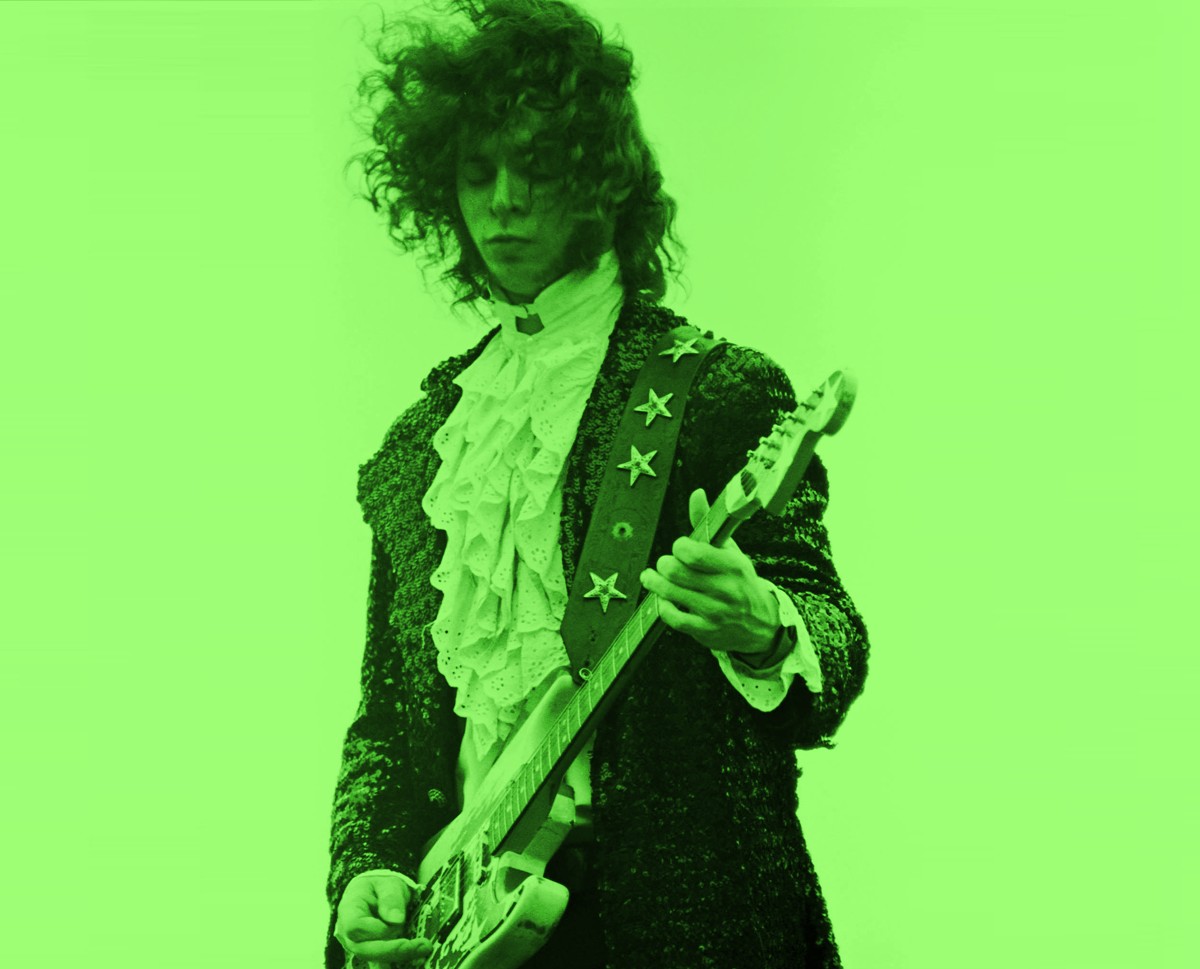

Beloved rock journalist and acquaintance of the band Ben Edmonds had reportedly been working on an MC5 book for decades before he died two years ago. And not to toot my own horn, but this writer made a valiant effort 10 years ago with Sonically Speaking. But there's nothing like an autobiography when it comes to really digging deep. Kramer's The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, the MC5 & My Life of Impossibilities does exactly that. It's simultaneously brutally honest, heartbreaking, hilarious, and life-affirming. The guitarist also does a great job detailing his time post-MC5, up to the 2003 DKT/MC5 reunion period and beyond. It's a frankly wonderful read. Here's an excerpt, to whet your appetite... —Brett Callwood

I was entirely committed to making the MC5 a success. In 1966, my last year at Cooley High, I would come home from school every day, open the phone book, and call anyplace that a band might play: teen centers, churches, schools, nightclubs, VFW halls, bowling alleys. I did everything I could think of to get exposure for the band. I knew that no one else could do it or was interested in the nuts and bolts of it, so I naturally gravitated to the leadership position. None of the other fellows in the band even had an inkling that this stuff needed to be done. I knew that if something was going to happen for us, it wouldn't be by magic. I had to make it happen. We all had a say in the creative side of the band, with Bob Derminer and me at the lead, and Fred Smith usually adding his solid agreement. But any business direction or effort was all on me. I did the heavy lifting, and I signed the contracts.

The bookers and club managers I knew were all telling me to learn the Top Ten, as it was called: the top ten songs on the radio charts. This was what the bands that got steady bar work did. There were scores of clubs with live music all over the city in those days. The factories were still going full time, three shifts a day, seven days a week. Our problem was we didn't want to be a bar band that played other bands' songs from the radio. We wanted our own songs on the radio, and to play concerts like our idols. The result was a house divided. Patrick Burrows and Bob Gaspar wanted to play top ten and work the clubs for the immediate money; while Bob Derminer, Fred Smith, and I wanted to develop our own original music and take over the world with it.

I had been experimenting with new sounds on the guitar, feedback and distortion. Bob Derminer was starting to write lyrics. I was listening to what some of the British guitar players were doing, and learning from them. Pete Townshend and Jeff Beck were doing the most advanced things with the electric guitar, and I was way into it. I discovered feedback for myself when I set my guitar down at rehearsal with the volume up and left the room. I heard this unholy howling sound coming from the basement, and then a crash. A jar of nails sitting on a shelf had vibrated off and broken on the floor. I told the guys, "I've discovered the power to change the universe: feedback." I could reproduce most of the things I heard the English guitarists play, and I was developing my own ideas about the sound of the electric guitar. I practiced a lot; it was both my obsession and my refuge.

At the time, bassist Pat Burrows was being forced to make a decision. Burrows was torn between his love of bassist James Jamerson and our avant-garde agenda. Smith and I conspired to force him out of the band. We bad-mouthed him behind his back because we wanted tall, thin guys with long hair who looked like the Rolling Stones or the Who.

The final straw came when Burrows showed up at rehearsal with his new Fender Precision Bass, just like Jamerson's. He had traded in the Höfner-style bass we'd chosen for him, and he was as proud as could be of his new instrument. But we castigated him for it, and he stormed out of rehearsal. Gone. The truth was that I would have done whatever I thought it took to succeed. I didn't appreciate Burrows' expertise; I just assumed that anyone could play the bass with soul, swing, and drive. My disrespect for Burrows and his talent would come back to bite me in the ass.

I had another guy waiting in the wings: The new bass player would be Michael Davis. I'd met Davis through Derminer; they both stayed in the same apartment building in the Cass Corridor downtown. Davis was a few years older than me, and he was beautiful — tall and thin, and a talented painter.

He served as a tutor for me in the ways of the world. A charming lady-killer, he had lived in New York City for a couple of years and knew all about drugs. I was an eager student. Davis, like Derminer before him, was not a bass player by his own volition. I decided that he would be the capstone in the band so, like Derminer and Smith, I'd teach him. He could play and sing Bob Dylan tunes on the guitar, so I figured it wouldn't be that much of a stretch to learn bass. We became fast friends as he transitioned from beatnik art student to MC5 bassist. I enjoyed his company immensely.

Then Bob Gaspar quit. He had to choose between our crazed avant-rock music and a steady job in a bank, and he went with the bank job. I had underappreciated his skills on the drums. He was a rock-steady backbeat hitter with great timing, feel, and energy, but I thought all drummers could do what he did.

I went on the hunt for a new drummer. We tried a few different guys, but none were willing to commit. I remembered a guy I knew, Dennis Tomich, from Lincoln Park, and he came out to audition. We were working a four-nights-a-week gig at the Crystal Bar, a terrible dive on Michigan Avenue where we played to an empty room most nights; maybe a neighborhood drunk or two nursing their beers. It was a lousy gig, but we were excited to have the job anyway. Tomich played a night or two with us, and we decided he'd be fine. We had a ceremony onstage to initiate him into the band. He was presented with the official MC5 toilet plunger to commemorate his membership.

Derminer decided to reinvent himself. From now on, he would be known as Robin Tyner. Tyner was the name of his favorite jazz piano player, McCoy Tyner. He also said that I should change my name to Kramer. I liked the idea; Kramer was more mainstream, less clunky than Kambes. To me, Kramer sounded more like an American consumer product. Like cheese or vacuum cleaners. "Yes sir, these new Kramer vacuums are top of the line."

But there was a deeper reason I went with the name change. This was the perfect way to finally get back at my spineless father for running out on us. He would never know that his son had become a famous musician, because I would have a different name. To hell with him! Now he could never share in my glory. Later, when I turned 17, I went to court and legally changed my name to Kramer. Now he would never know. Revenge was mine.

Tyner also added a fictional "Bartholomew" to Fred's name: Frederick Bartholomew Smith. It had a nice Euro-ring to it. Later Smith revised it to Fred "Sonic" Smith. New drummer Tomich was christened Dennis "Machine Gun" Thompson, and for a minute Michael Davis became "Mick Davies." Tyner was a very creative dude.

Not long after the name change, I smoked my first joint in the parking lot before one of our "record hop" gigs. I knew Tyner and Davis smoked pot, and I wanted to try it. From what I understood, there was no hangover like with liquor, and my mother wouldn't be able to smell it on my breath. We were waiting in the car for showtime and they broke out a joint. The reefer messed up my sense of time, and I was obsessively checking my watch every couple of minutes. The absurdity of my preoccupation with being on time was cracking us up. Everything took on a hysterical note. We were laughing our asses off. After that, I was sold on marijuana.

Excerpted from The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, the MC5 & My Life of Impossibilities by Wayne Kramer. Available from Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.