Standing on her front porch, Bettie Simmons can plainly point out why an environmental justice movement is so necessary.

"Look, I just cleaned this last week," the 71-year-old says as she points to the black dust that collects in clumps on window frames of her southwest Detroit home. "It didn't use to be like that here."

At his home nearby, Roland Wahl has mysterious gluey silver particles stuck on his backyard grill cover. "Some of the particles are so fine, they're like powdered sugar. And you breathe them," he says. He's also annoyed by the roar of the trucks that carry supplies, equipment and more workers to nearby industrial sites that weren't there when he moved in 40 years ago.

Up the street from Wahl, Linda Chernowas often finds a black, oily film on the pool in her yard. She describes it in a raspy voice. She's been diagnosed with reflex laryngitis, and her doctor told her to move out of her neighborhood, believing the pollution is exacerbating her condition.

The three are longtime residents of the area near where I-75 crosses the Rouge River. It's within ZIP code 48217.

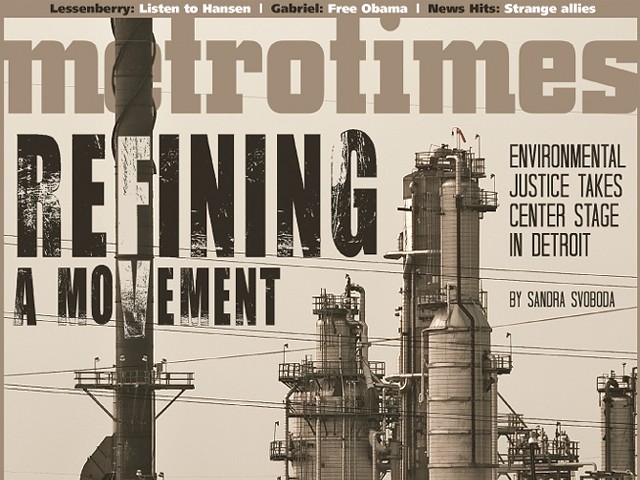

Simmons, Chernowas and Wahl insist it was nothing like this when they and other long-time residents moved to the area. Now they say the continued industrial development — the Marathon Petroleum oil refinery expansion, new sewage treatment facilities, asphalt yards and other heavy industry — has diminished their quality of life and is damaging their health.

They'd sell their homes and move, but what can they get for them? The recent real estate downturn is bad enough, but the area's continued industrialization leaves them little hope. Who would buy a house and move to a street with trucks roaring by, the smell of sewage treatment in the air and the smoky glow of the oil refinery dominating the skyline?

The Detroit City Council has refused residents requests for a moratorium on industrial development in the area. That would cost the city much-needed jobs. And residents protested in 2007 before the council approved Marathon's $2.2 billion expansion in a deal that included about $176 million over 20 years in property tax exemptions.

These residents are on the frontline of the environmental justice movement, the roughly 35-year-old effort to ensure that minority and low-income communities aren't disproportionately paying the high price of industrialization with their health, quality of life and property values.

Environmental justice advocates — largely local community organizations but a growing number of government bureaucrats — seek to draw attention to the human costs of "progress" and protect the residents who live near pollution sources.

It's where environmental advocacy and civil rights meet to demonstrate the consequences of capitalism that are often brushed aside in the quest for development and profits. The movement is about establishing a balance — or at least making sure residents are considered in plans for development, expanded industry and construction projects.

"The main difference between regular environmental protectionism and advocacy and environmental justice is we bring human beings into the equation," says Patrick Geans-Ali, communications coordinator at East Michigan Environmental Action Council. "Typically, with most environmental groups — and we're about this 100 percent as well — it's land protection, air quality, water quality, land use, animal rights and protection. We're for all those things, but we feel a lot of the time when it comes to environmental justice, what's missing is the protection of human beings."

And in its 35 years, the environmental justice movement has had varying successes and failures.

"It's still a struggle," says Robert Bullard, director of the Environmental Justice Resource Center at Clark Atlanta University and widely considered one of the movement's pioneers. "The environmental justice community is saying we need to make sure the EPA and other agencies hold the line."

Bullard says the movement suffered "a great deal of slippage and pushback" under Bush administration policies that favored industry over "costly" regulations and extensive permitting. But Bullard credits President Barack Obama and his EPA administrator for making environmental justice a priority for the agency.

That attention has not come without critics. An Investor's Business Daily editorial in October wondered if "green socialism" was the EPA's goal and criticized the agency for hiring an environmental justice coordinator. And the current climate in the U.S. House of Representatives could put roadblocks in the movement's path.

Reps. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) and Edward Markey (D-Mass.) recently released a list of 110 anti-environment votes taken in the house this year. Waxman, the ranking Democrat on the House Energy and Commerce Committee, calls this chamber "the most anti-environment House of Representatives in history" intent on removing controls on power plants, oil refineries and factories in the name of jobs and profits.

But movement leaders insist environmental justice has an important economic development component, especially for people who live near industry.

"We do green jobs," says Sandra Yu, a program manager at the nonprofit Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, "but we've also got to do advocacy work that produces policy that encourages local people getting hired in projects."

As the environmental justice movement refocuses for the 21st century, it also seeks to increase and support the green economy and increase collaboration between grassroots environmental justice and community groups and governmental agencies.

"If I had to really define the environmental justice movement in 2011, it would be that it still defines environmental in the context of where we live, work, play, learn and worship, as well as the physical and natural world. It emphasizes the whole idea that the movement is a grassroots, bottom-up, community-based movement," Bullard says.

"We emphasize the whole idea that a centerpiece of the justice movement is that we speak for ourselves. That's still a theme that says communities that are the most impacted should be able to speak for themselves."

Strategies for doing that will be part of a national environmental justice conference in Detroit next week, only the fourth such annual gathering sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. It will draw an expected 500 participants. The conferences themselves are one measure of how what began as a protest movement has had an impact and influence on the establishment.

"We want to be a catalyst for Detroit becoming this new urban center where everyone could thrive in economic, environmental and social health. In pursuit of that goal, we focus on green jobs, civic engagement and sustainable development," says Yu, who is involved with planning the conference. "If you're talking about sustainable development, we don't want it to happen to people, we want it to happen together."

The national conference, headquartered at the Detroit Marriott at the Renaissance Center, will hold meetings downtown that will focus on green job creation, the detection of pollution sources, and how to build better relationships between governmental agencies and community groups.

"Having the meeting in Detroit is more than just symbolic," Bullard says. "Detroit used to be the Motor City. It used to be a city of homes. Detroit used to be one of the major industrial manufacturing cities in the country."

Attendees — state and federal governmental workers, and local and national environmental justice advocates — will tour the southwest Detroit neighborhoods where Simmons, Chernowas and Wahl live to see what toll the residents are paying for the past and present industry in the area.

"We always do a community tour so people can actually go out and see what some of the folks are dealing with," says Laura McKelvey, group leader of the office of air quality, planning and standards in the community and tribal programs group at the EPA. "It's a great learning experience for the federal participants so they can get an on-the-ground sense of what people out in the real world are facing."

Patterns of pollution

Beginning in the late 1970s, environmental justice advocates started fighting against and publicizing the siting of landfills, incinerators and other polluting facilities in minority and low-income areas. The first landmark dispute was a 1979 case in Houston, where African-American homeowners fought to keep a landfill out of their suburban neighborhood. The resulting lawsuit was the first to challenge the location of a waste facility using federal civil rights law.

Three years later, protests over the location of a PCB-laden landfill in North Carolina — in a rural, mostly African-American county — drew national attention. That led to a 1983 U.S. General Accounting Office study that found about 75 percent of hazardous waste landfills in eight Southern states were in predominantly black communities.

Then in 1987, the national study "Toxic Waste and Race" found that race — not income level, land value or homeownership rates — was the most powerful predictor of where waste facility sites were located.

"It's no coincidence that the majority of landfills, waste facilities, industrial waste sites are in communities of color," says Richard Hofrichter, the senior director of health equity at the National Association of County and City Health Officials. "You can't explain that away too easily. There's a pattern."

With the election of President Bill Clinton in 1992, environmental justice advocates got significant support. In 1994, Clinton signed an executive order directing federal agencies to make environmental justice part of their mission by identifying and addressing disproportionate and adverse impacts of programs, policies and activities on minority and low-income populations.

What had largely been a decentralized effort — community organizations in different parts of the country working toward largely local outcomes — now had the backing within the federal government.

Part of what that executive order mandated was that federal agencies identify disparate impacts of policies and projects on minority and low-income populations, but also work to prevent them. Another part of that effort included ensuring better public participation related to federal programs and activities.

After the executive order, environmental justice-related impacts started to be considered by regulators in what permits were granted and what rules and regulations applied to industry and state and local agencies that received federal money, the EPA's McKelvey says.

Those ideas are now part of her office's focus on air quality standards. The EPA is also working harder to involve affected communities in the writing of regulations, McKelvey says.

"We do a lot of translation of the technical stuff for the community folks, and also take the community concerns to the technical people so their feedback can make it into the rules," she says. "We always look at our regulatory impact analysis, looking at impacts on the economy and impacts on the public health. Now we're adding components of looking at who lives around the sources."

President Barack Obama's 2009 appointment of Lisa Jackson as the EPA administrator has also raised the profile of environmental justice principles for the agency's work. A chemical engineer who has spent most of her career with the EPA, she has publicly pledged that cleaning up communities and working for environmental justice are among her top priorities

"The increase in the conversation on environmentalism and environmental justice has been a priority for the administrator for the term she's been here, and it really has opened the door for doing more and bringing people to the table," McKelvey says.

Earlier this month, the leaders of 17 federal agencies signed a memo of understanding on environmental justice, underscoring its importance in the federal government's activities.

How environmental justice will play in Michigan's new administration is an altogether different question.

Michigan efforts

In her final days as governor, Jennifer Granholm endorsed an environmental justice plan for the state of Michigan and the then-Department of Natural Resources and Environment. It was intended to ensure no group would bear a disproportionate burden of environmental laws, regulations and policies, and to better involve community residents in planning and permitting hearings. It was the result of two years of work by a 44-member panel. Representatives came from state government, the advocacy community, industry including DTE and Dow Chemical Co., the Detroit Regional Chamber and universities.

The resulting plan is actually a series of recommendations to guide state departments in identifying and preventing discriminatory public health or environmental effects of state actions. The guidelines also cover ways to improve public outreach and involvement related to some projects and to foster cooperation with and between existing programs administered by federal, state and local governments as well as coalitions of environmental justice advocates.

The plan also seeks to balance environmental justice and economic growth.

"All too often, environmental justice considerations are framed in negative terms and perceived as potential obstacles to economic growth," the executive summary reads. "Minority and low-income communities, no less than other communities, want vibrant businesses that add to their economic base without harming their individual health and well-being. Accordingly, this environmental justice plan is not designed or intended to run contrary to the larger economic development efforts of the state. Instead, the focus of this plan, and the hope of the working group, is that this plan provides the best avenue for balancing productive economic growth with the high quality of life that is important to all people."

It also calls for the training of state workers, identification of an environmental justice coordinator in the DNR, and strong leadership from the executive branch on environmental justice issues.

But since Granholm signed the plan and Gov. Rick Snyder took office in January, little has happened.

"The plan was finalized under the previous administration and the current administration has not taken an official position on the plan or on environmental justice in general," says Bryce Feighner, chief of the office of environmental assistance at the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. "There's been no statement saying, 'Go forward with this plan.'"

Metro Times inquiries to Gov. Snyder's office were unanswered.

The December 2010 plan doesn't mandate any conditions for permitting of, for instance, power plants or landfills. Participants decided to leave that to the feds, Feighner says. "People felt the teeth, the regulatory aspects that could impact environmental justice, should come from the federal government," he says.

Other state agencies have been incorporating some of the federal environmental justice guidelines for years, partially because they are mandated if federal money is involved in projects. For example, the Michigan Department of Transportation, since the mid-1990s, has at least identified what the impacts of projects are on neighborhoods, says Lori Noblet, an environmental justice specialist at MDOT.

"The key for environmental justice is to have outreach and involve [the community] in the process, to have public information meetings and public hearings to allow the community an opportunity to review the proposed alternatives that are on the table at the time and provide feedback as to what they think some of the impacts might be or anything else we need to know," Noblet says.

The new pedestrian-bicycle bridge across I-75 in Mexicantown is an example of an MDOT project that attempted to remedy a past injustice to people living in that community. When the interstate was constructed nearly 40 years ago, it displaced the residents and homes in its path. It interrupted Bagley Street and other surface roads and isolated Mexicantown from surrounding communities.

But when planners were designing the Gateway Project, the construction project to improve traffic flow at the intersection of I-75, I-96 and the Ambassador Bridge, they revisited the past problem.

"When they were doing the Gateway Project, in order to reconnect the community back together, they built the pedestrian bridge," Noblet says. It opened last year.

And as federal funds for highway construction come with questions about environmental justice considerations, transportation planners have to have those answers.

"Since 1994, when [President Clinton's] executive order was passed and in the last 10 years, it has notched up," says Ola Williams, an environmental justice specialist in MDOT's statewide planning section. "The feds are asking for more information and the [local planners] are digging deeper."

The concept of environmental justice is starting to reach into local governments as well.

Ingham County this year hired an environmental justice coordinator to work with the health department on health equity, access to care, and promoting healthy communities. That includes, for example, supporting efforts like the maintenance and construction of parks and other recreational areas, ensuring safe housing and researching air quality issues.

"The position has really begun to look more at the root causes of health inequities ... those being institutional racism, gender oppression and class inequity," says Renee Canady, the deputy health officer at the Ingham County Health Department, "There are tons of environmental correlates to poor health outcomes. ... What we are trying to do is ... set up a structure that holds the system accountable. ... We know there are individual components to health but that is not the complete conversation. We are trying to establish a forum for having the complete conversation."

The department hired Jessica Yorko as the environmental justice coordinator. Since she started, she's researched the major environmental health problems in the mid-Michigan county and found two of them to be childhood asthma and lead poisoning. "What we're seeing is it's not just access to health care, it's also healthy environments. Those two things both need to happen," Yorko says.

She follows the "healthy communities" work around the state and says Detroit is home to several model environmental justice groups. And those groups, not the government, are the true home of the environmental justice movement.

Detroit's environment and justice

Ask Rhonda Anderson what environmental justice in Detroit involves and she gives a diverse list of answers. Among them, the traditional environmental concerns include lead in residential soil, high asthma rates, the Detroit incinerator, the heavy industry in southwest Detroit and the resulting effects on residents' health and homes.

But she also talks about broader community needs that would help residents communicate about their environmental conditions: the desirability of having computer labs available around the city for residents who can't afford computers or Internet service, and the need for programs to train community groups to create their own media — YouTube videos, social networking sites and more — to publicize their message.

"What they've lacked is resources, tools and information. By providing those things to the people at the bottom, you can raise up all of the city of Detroit," Anderson says.

Anderson is the environmental justice coordinator for the Sierra Club's Detroit office, one of the few grassroots organizers with the backing of a national group.

Wary of charges several decades ago that mainstream environmental organizations were not addressing minority communities, the Sierra Club's national office established a handful of coordinators like Anderson around the country. They now work on issues related to Native American lands as well as coal mining and mountaintop removal in poor Appalachian communities.

"That puts the Sierra Club, I would say, in a different category than other larger environmental organizations," Anderson says. "These communities are not only experiencing the environmental impact but they're also experiencing the detrimental impact on their health and their quality of life."

Top Michigan concerns for the club include waste management and coal-fired plants. Anderson says she spends a lot of time with residents of southwest Detroit, especially those like Simmons, Chernowas and Wahl who live near the massive refinery expansion.

"You're not going to get rid of industries like oil refining, but you also need to consider the people that live around the dirty, polluting facilities," Anderson says. "For many of us, we can sit in our clean little homes in the outer areas and we don't have to be concerned about that environmental impact. ... But when you can't see that dirty thing it's out of sight, out of mind."

Like others in the present environmental justice movement, Anderson is an economic realist.

"We're not asking for plants to close down. We know they provide good jobs. That's the sense and idea around green job development. We want all of that, but we also want these dirty, polluting industries to clean themselves up."

It doesn't have to be one or the other, she says. "I believe we can have good jobs, good-paying jobs and have a cleaner environment. The technology is there. But industry, in its attempt to make as much money as it can, is going to insist it's going to cost them money."

But those in the movement stress there should be a market for green jobs — asbestos removal, hazardous waste cleanup, brownfield cleanup and redevelopment, environmental site assessment and the dismantling of buildings to reuse and recycle their components — and that communities that have faced the brunt of the pollution should see some of those jobs.

That's where another Detroit nonprofit comes in. Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice also works on traditional environmental concerns, such as the city's waste-to-energy incinerator, abandoned homes and vacant land. But the group also participates in a federal grant to do green jobs training at Wayne County Community College. Residents of certain Detroit ZIP codes receive priority admittance to the program to learn construction, deconstruction and other green employment skills.

It's part of the broader vision of environmental justice, making healthier communities, training employees for jobs, and greening up everything along the way.

"I see it as highest quality development," says Yu, from DWEJ. "If you're going to do housing rehab, make it energy-efficient. If you're doing to do a park, let's not make it a water hog. If you're going to redo streets, can we make them both complete streets and have them help with storm water management? There are lots of ways we can make better quality development. Healthier, cleaner, reducing the load on city services like water and lighting and utilities."

'The new sexy'

The discovery and promotion of the principles of environmental justice by many, including industry and the government, make Ahmina Maxey wary. She's the deputy director at the East Michigan Environmental Action Council, a group that's changed its own course in recent years.

Founded about three decades ago, the group for a while was headquartered in the suburbs and largely advocated for basic environmental policy. Then, a few years ago, the group's new director moved the offices back downtown, sought grants, added staff and programs, and now works on a number of issues in the city as well as youth programs. Media literacy, school programs and a youth film festival all have an environmental justice focus.

Maxey saw a resurgence of energy and coordination of environmental justice groups after last year's U.S. Social Forum in Detroit. But she cautions against assigning too much optimism to governmental attention or more mainstream environmental groups.

"Environmental justice is the new sexy," she says. "But, it's like, are you really for environmental justice or are you using people of color and in low-income communities to further your organization or further your bottom line. That's detrimental to the environmental justice movement because if it gets watered down, it gets ruined."

She will attend the conference, having helped organize some sessions, and hopes it will help accomplish better collaboration among local nonprofits as well as put some pressure on local and state officials to better address environmental concerns in the city.

"The environmental justice movement is coming together," she says. "We have to be vocal and really push forward the true definition of environmental justice, which is the access to clean air, water and land for all people ... but especially that communities of color and low-income communities aren't disproportionately burdened."

The 2011 Environmental Justice Conference, One Community — One Environment, is open to the public. It will be held Aug. 23-26 at the Detroit Marriott at the Renaissance Center. More information is available at cleanairinfo.com/ejconference.