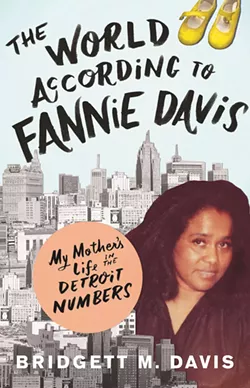

In her new memoir The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother's Life in the Detroit Numbers, author Bridgett Davis recounts how her mother was able to provide for her family as a Numbers runner. This excerpt is reprinted with permission.

The Numbers business in Detroit was still thriving in the 1950s. In fact, the Numbers were by then ubiquitous in black communities throughout the country. I'd venture to say that nearly every black person over 40 is familiar with the Numbers — played them, knows people who played them, and knows about someone who ran them. Or still runs them. It is impossible to overstate the role of the Numbers in black culture. Just as Aunt Florence was playing numbers back in Nashville and sending "a little piece of change" to her sister up North, black folks in cities across the country were doing likewise. August Wilson's play Fences, set in 1950s Pittsburgh, includes an exchange between Rose and Troy about the Numbers: "That 651 hit yesterday," says Rose. "That's the second time this month. Miss Pearl hit for a dollar ... seem like those that need the least always get lucky. Poor folks can't get nothing." Troy retorts: "Them numbers don't know nobody. I don't know why you fool with them." Rose reminds Troy, "Now I hit sometimes. ... It always comes in handy. ... I don't hear you complaining then."

Lotteries date back to the beginning of this country. All 13 original colonies operated legal lottery businesses that were precursors to the country's stock market and thrived well into the 19th century; they soon became a huge, professional business, in fact the "genesis of American big business," according to the authors of Playing the Numbers. Indeed, proceeds from lotteries were used to finance all kinds of capital improvements, like roads and bridges, for the cash-starved colonies.

At the same time, it's part of the African-American tradition to use lottery playing to better one's conditions in a society that has systematically subjugated its black population. That tradition includes Denmark Vesey, a Charleston slave, who later was executed for planning a revolt against slave owners. Vesey used $1,500 he won from the city lottery in 1799 to buy his freedom. Vesey also helped found the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, where over 200 years later a white supremacist shot dead nine African-Americans during a Bible class.

From the early days, African-Americans didn't just wager as part of the legal lottery system. Rather, they engaged — along with poorer whites — in an ingenious game played alongside these legal lotteries. For a fraction of the cost of a lottery ticket, a person could "insure" or "take a policy on" a number with an agent, effectively betting that a particular number would be drawn in a lottery on a given day. This game was called "insuring the lottery," or "policy," and was a way to make a side wager on the official state lotteries.

Antilottery laws were enacted in all but three states by 1860, similar in large measure to so many laws in America that were designed to thwart the efforts of free blacks to acquire wealth-based equality. The abolition of lotteries had the unintended but unsurprising consequence of huge increases in the amount of money gambled on policy. Winning numbers apparently came from drawings in the states that still had legal lotteries (Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware), and those winning digits were chosen via a large barrel with slips of paper in it, each with a number from one to 78; 12 numbers were drawn in the morning, and 13 numbers were drawn at night. The winning numbers were then telegraphed "in cipher" to the policy headquarters in other states. One press report claims the winning numbers were picked out of a barrel in Louisville, Kentucky, by "a blind Negro." Policy kings most certainly fixed numbers and made it even harder for folks to win. If the policy game was played fairly, the estimated odds of winning were a staggering one in 70,000. Still, people played policy in droves. And from the start, blacks indulged disproportionately. Indeed, in those early decades of freedom from slavery, during Reconstruction, many blacks were free in theory only, facing such grim financial lives that it's easy to see the lure of indulging in a practice that could transform small amounts of money into large sums.

Policy shops, as they were called, were run almost exclusively by whites and proliferated throughout the country. These big businesses were run in full view of and with the cooperation of police. Their owners often employed black men as agents in order to lure black customers. Unsurprisingly, the business was rife with cheating and exploitation, as well as payoffs to police and politicians. So too began the denigration of lottery players, and the correlation among bettors, African-Americans, the poor, and fools. The press especially equated a defective character with betting on numbers. As early as 1887, two years after my mother's father was born, a Detroit Free Press headline blared: "The deadly policy shop and its 'coon row' gig." The story's lede proclaimed, "Policy is generally the poor man's game and is played mostly by colored men, cheap waiters, and 'tin-horn' gamblers."

In 1890 Congress passed an antilottery bill, and by 1894 all states had abolished lotteries. But that stopped nothing. Apparently still using numbers based on surreptitious drawings in Kentucky, the illegal lottery business thrived. At the outset of the 20th century, the Detroit Free Press was hysterically and repeatedly reporting on the ways in which policy was ruining Detroit society, noting that the police force accepted bribes and payoffs so gambling could flourish.

In an article in The Detroit Free Press on March 30, 1903, the reporter made clear the disdain with which the newspaper viewed policy players:

It is largely the gambling field of the ignorant, superstitious, and poor, though more than one man having a prosperous little business has lost his all because infatuated with this lightly veneered form of robbery. It is responsible for no end of suffering, promotes crime, and adds to the public expense in the support of the dependent. The main thing is to have the evil eternally wiped out, which the police authorities can do if they want to.

According to the newspaper, by 1906, policy had been "stamped out" by police. But by 1908 a brief resurgence occurred, as "energetic colored agents" apparently attempted to revive the "industry" and "policy bids fair again to monopolize much of the attention, as well as the money, of the colored gamesters." And as late as 1915, the paper reported on a police raid of "Negro gambling houses" on St. Antoine Street and Hastings Street on the city's east side, resulting in "10 Negroes being locked up"; on the same day, police raided a pool hall on Grand River, where 12 more men were locked up, along with four Negro women, for larceny.

Policy seemed to have died down considerably, if not completely, by the onset of World War I; yet its negative association with African-Americans was solidified, no matter that whites bet heavily alongside them. Numbers gambling as we know it today — the mother of today's state lotteries — was invented in Harlem in the early 1920s. And while there's speculation that versions of the Numbers game were introduced in the first decades of the 1900s, brought to Harlem by migrants from Cuba, the British West Indies, and Puerto Rico, historians say the widely held belief is that a black man named Casper Holstein invented the scheme as it is still played today.

Holstein, born in the Danish West Indies, was a Brooklyn high school graduate who, like the majority of colored men and women in America, was barred from using his talents in a chosen field, so he worked as a porter for a Fifth Avenue store. As the legend goes, in 1920 or 1921, he was sitting in a janitor's room for hours, deeply studying the "Clearing House" totals printed each day in a year's worth of newspapers that he'd saved. The Clearing House was a financial institution that facilitated the daily exchanges and settlements of money among New York's banks. It occurred to Holstein that the numbers printed in the paper were different every day. Within months he came up with his scheme — he'd take the first two digits from the first total published by the Clearing House and one digit from the second total and create a daily three-digit winning number. If a player hit, he or she would be paid 600 to 1. It was an elegant system for many reasons. It didn't rely on dubious drawings in other states, or on complicated calculations; everyone could have access to the winning numbers at the same time, and the source was unimpeachable. But the most important reason for its beauty was this: Unlike the policy, Numbers was a black-owned and black-controlled business.

The Numbers blossomed into a lucrative shadow economy in the early 1920s, and moved into black communities across America, thanks in large part to the Great Migration. From 1915 to 1930, well over a million black Southerners moved to the North. Given its role as a viable economic base — in Harlem alone the New York Age estimated that in 1926 the daily turnover on numbers was $75,000, with an annual turnover of $20 million — many saw it as black folks' own stock market. While some still referred to the business as "policy" for a few years, it was the newer, wondrous system known as the Numbers that had free rein over the lottery-playing market for 70 years — until the first legal state lottery was reintroduced in 1964.

Once the game as we know it was introduced to Detroit, it quickly became a de facto informal economy, filling the void left by a formal economy that largely excluded African-Americans. Pushing against rampant discrimination, local Numbers operators used their profits to found legitimate businesses, providing migrant blacks with all kinds of access they wouldn't otherwise have had. They launched insurance companies, newspapers, loan offices, real estate firms, scholarships for college, and more. As such, these big Numbers men used their own wealth not only to enrich themselves, but also to combat racism and uplift the race. The Numbers quickly morphed into a thriving, sprawling underground enterprise, so intertwined with the city's lifeblood that it helped shape Detroit's 20th-century identity. No better example exists than that of John Roxborough, the educated, upper-class black man who brought the Numbers to Detroit; as the city's biggest Numbers man in the 1930s, he used his largesse and business acumen to manage and invest heavily in boxer Joe Louis. Nicknamed the Brown Bomber, Louis became heavyweight champion of the world, knocking down racial stereotypes as both a hometown champ and an American hero. Today, the iconic memorial sculpture of the Brown Bomber's fist is what greets you at the epicenter of downtown Detroit. The Fist represents his punch against Jim Crow laws as well as his opponents, and has become synonymous with black Detroiters' fight for racial justice. And the Numbers made it all possible.

The Numbers also became inextricably tied to the auto industry. In fact, the plants unwittingly abetted the Numbers' rise. Factory workers functioned as runners, collecting bets and money from other workers, then turning it all in to bookies and bankers. Ford Motor Co.'s River Rouge plant, one of the largest industrial complexes in the world, which employed 85,000 workers by the end of World War II, had for decades a flourishing Numbers business. Between 1947 and 1951, The Washington Post, the New York Times, and The Los Angeles Times all reported on this phenomenon as national news. One report claimed that the Numbers were a $15,000-a-day business within the Rouge plant, while another estimated them to be a $5-million-a-year enterprise. The New York Times lamented in an editorial that Detroit's "numbers game" threatened plant discipline and claimed that "this evil has been linked to underworld elements that permeate the workplace." My parents weren't part of that so-called underworld, but they were well aware of it. Mama and Daddy had both played Numbers for a few coins and had seen their neighbors and friends play them too, regularly. Mama took notice.

On a frigid winter night, my mother showed up at her brother's home and banged on his door. "Woke me up and everything," Uncle John recalls. She stepped inside and stood before him, not even bothering to take off her coat.

"I want to try to bank the Numbers," she announced.

Bridgett Davis will do a book talk and signing for The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother's Life in the Detroit Numbers from noon-2 p.m. on Saturday, Feb. 9 at the Detroit Historical Museum; 5401 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-833-7935; detroithistorical.org; and 2-4 p.m. on Sunday, Feb. 10 at the Detroit Public Library Main Branch; 5201 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-481-1300; detroitpubliclibrary.org. Both events are free and open to the public, and books will be available to purchase.