Dan Stamper emerged from an afternoon stay in jail last week full of defiance. Despite being found in contempt by a Wayne County Circuit Court Judge, the president of the Detroit International Bridge Co. came out swinging.

For nearly a year, the company owned by billionaire trucking mogul Manuel "Matty" Moroun had ignored a court order to begin complying with a contract it had with the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT).

The contract spelled out the obligations of both the company and the state in regard to the public-private Gateway Project in southwest Detroit. The $230 million endeavor involved a massive amount of roadwork to provide direct freeway access to the Ambassador Bridge, which is also owned by Moroun's company.

The problem, from the state's point of view, was that it had lived up to its end of the bargain, but the company had not. Instead of adhering to the plans laid out in the agreement, alleged the state, the company made significant design changes without receiving approval from MDOT.

In February of last year, after a trial, Judge Edwards sided with the state and ordered the company to tear down what it had constructed that was in conflict with the original design and go back and build what it had agreed to.

Instead of complying with the judge's order, the company twice tried to have the case moved to federal court. Following the company's second unsuccessful attempt, U.S. District Judge Patrick Duggan observed:

"Considering this Court's more than 33 years as a judicial officer, DIBC may be entitled to its recognition as the party who has devised the most creative schemes and maneuvers to delay compliance with a court order."

Duggan sent the case back to Edwards, who was none too happy with the company's lack of compliance. And so he sent Stamper to the slammer for a few hours to drive home the message that he was serious about getting the work done. Stamper, the judge said, would remain in jail until the company began adhering to his order.

Within a few hours, a crew was on site at the bridge company's truck plaza, beginning work on a small maintenance road that the company was obligated to build. In addition, the company was ordered to develop a schedule to complete the work within a year, and to meet with a court-appointed monitor and MDOT every two weeks to show that the schedule is being adhered to.

Instead of admitting fault, however, Stamper emerged from jail and immediately began blaming the state for the company's problems.

The DIBC wants to build a new bridge adjacent to the Ambassador. In interviews with the Metro Times, MDOT has consistently voiced support for that second privately owned span. But it is also in support of a new publicly owned bridge the department, along with the federal government and Canada, want to build more than a mile downriver in the Delray area of Detroit.

That downriver bridge, Stamper claimed, is the reason MDOT has been playing hardball with the company.

"MDOT bureaucrats are doing everything they can to stop our successful 80-year-old private sector business from building our new bridge with our own money," Stamper said in a statement issued following his release. "They will lose. This won't stop us, and our new bridge will be built and serve the public well."

However, what emerged from the action in Edwards' court is an entirely different picture. Instead of being an innocent victim of vengeful bureaucrats, the company was characterized as an organization that wanted to play by its own rules as it looked to maximize its profits at the expense of the surrounding community.

The intent of the Gateway Project, in addition to facilitating the flow of commerce across the busiest border crossing in North America, was to remove bridge truck traffic from surface streets in southwest Detroit.

If the company didn't adhere to its share of the plan and make sure that objective was accomplished, the state faced the very real possibility of having to return $145 million the federal government contributed to the project.

Another problem, according to the state, is that the company was attempting to construct its share of the project in a way that would force all traffic to go past its privately owned fueling stations and duty-free shop. It wanted, in a sense, a captive customer base that had no choice. The state has insisted that bridge traffic have a choice: go through the bridge company property or directly onto the bridge.

The important word there is choice. The company tried to deny it while the state is mandating that it be ensured.

And that gets to the heart of the issue. While the company has tried to portray the state as being unreasonable and hostile, the state has been contending that the company is attempting to maximize its economic interests to the public's detriment.

At press time, the company still had not decided whether it will appeal Edwards' ruling in state court.

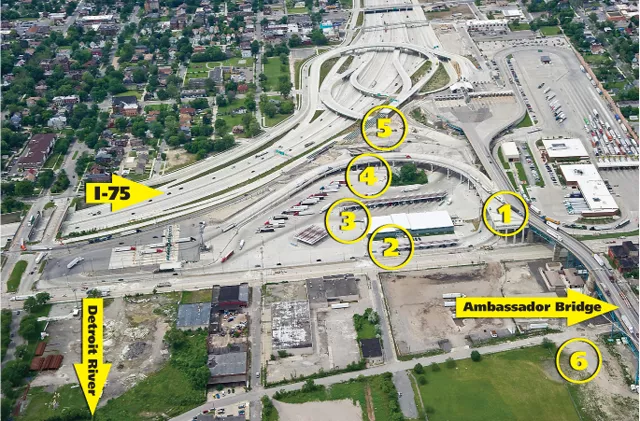

What follows is an explanation of some of the design issues at the core of the case, and what the company must do to comply with the court's order.

1. Identified in court as "Pier 19," this is the approach ramp to the bridge company's hoped-for new span — a bridge that has yet to be approved by either the Canadian or U.S. federal governments. The problem with Pier 19 is that it stands in the way of a road that is supposed to go through the bridge company's truck plaza, taking traffic off of Fort Street. It is one of the structures that must be removed.

2. A line of fueling pumps was also built where the new road adjacent to Fort Street is intended to be. The bridge company argued in court that the road isn't necessary and that it should be allowed to let truck traffic continue using Fort Street instead. These fueling pumps and underground tanks need to be removed. However, because of changes in property ownership that have occurred since the deal was first struck, the state now says that it may agree to remove the stipulation that the new road has to be elevated so that it passes over 23rd Street.

3. 23rd Street: Because the bridge company did not own all of the property in the area where it built its sprawling truck plaza, the original plan required that the city's 23rd Street remain open to provide access to local traffic. The company ignored that part of the plan and, without obtaining permission from the city, fenced off the street and paved it over, placing more fuel pumps in its path. The city is currently in the process of ceding legal control of 23rd Street to the bridge company.

4. This small patch of green in a sea of concrete was, until just recently, home to the Lafayette Bait & Tackle shop, which was left virtually stranded as a result of the company's unilateral closing of 23rd Street. While Judge Edwards was hearing arguments as to whether the bridge company should be held in contempt, the company purchased the property from the privately held Commodities Export Co. Bridge company lawyers complained in court that the land was being held for "ransom." Published reports indicate that the property was purchased for somewhere between $2 million and $20 million, with the speculation that the price was closer to $20 million.

5. This shows the location of one of several ramps the state is obligated to construct but has not opened. The bridge company insists that the delay is a form of retaliation by the state. The state contends that it can't open the ramps until the company builds its part of the project according to the agreed-upon plans. To do otherwise would be to risk losing the federal government's $145 million contribution to the project.

6. Although not part of the MDOT lawsuit, the city's Riverside Park Extension is an integral part of this issue. Shortly after 9/11, the company fenced off a 150-foot swath of parkland, claiming it was needed to protect the bridge from terrorists. For more than two years, the city has been in court in an attempt to get the company to take down the fence. As the above photo shows, the commandeered parkland is directly in the path of Pier 19. For the company to obtain permission from the U.S. Coast Guard to build its new bridge, it must first own all the property necessary to construct that span. However, there is no indication at this point the city is willing to sell. Another court hearing regarding the issue of the fence is expected to be held this week.