The made-for-TV movie of LeFlore's life was called One in a Million, and while that figure isn't accurate when viewed through a few disparate lenses, his story was extremely rare when it happened — and, arguably, could not possibly happen today. Even a film based on his life would be subject to backlash for being a "white savior" story, if it were produced at all. But LeFlore himself is quick to credit and thank the men responsible for his baseball career.

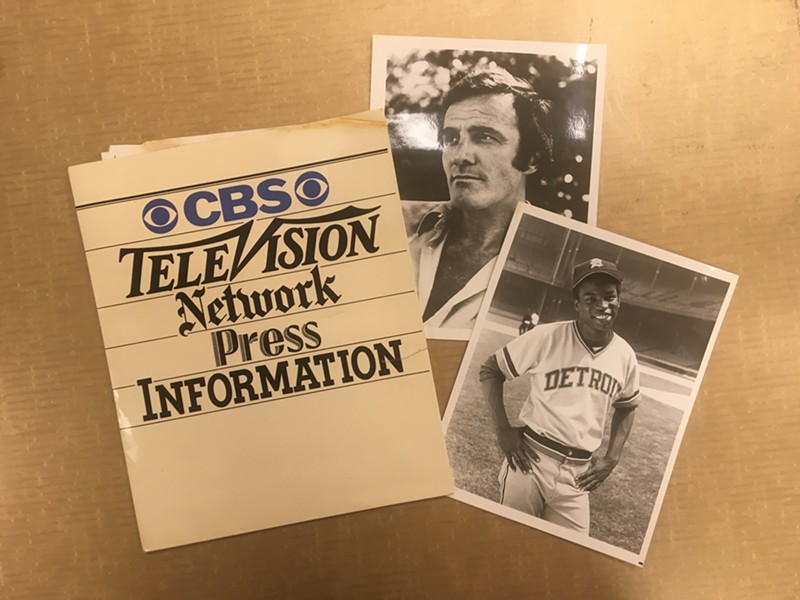

One in a Million: The Ron LeFlore Story starring a young LeVar Burton first aired on CBS in September of 1978, and it will be shown Sunday at the Detroit Historical Museum, 45 years to the month after LeFlore made his major-league baseball debut.

A native of Detroit's east side, LeFlore got in trouble with the law early and often and, in 1970, at the age of 21, he was arrested for the armed robbery of Dee's Bar on Mack Avenue, across from the Chrysler Stamping Plant. He was sentenced to five-to-15 years in the State Prison of Southern Michigan (commonly referred to as "Jackson Prison").

LeFlore's narrative is not one of a promising young athlete who is falsely convicted or a "wrong-place-at-the-wrong-time" tale of woe of an otherwise model citizen. He doesn't shy away from details of the robbery that led to his incarceration. When asked about any inaccuracies in the movie, he says, "The robbery scene. The way LeVar holds the gun." LeFlore chuckles. "That's not the way I held the gun."

LeFlore, by his own admission, was a booze and dope user and career criminal from a young age. Bios of him tend to point to his neighborhood (the LeFlore family lived on Iroquois near East Warren Avenue) or rough home life as tacit excuses for his criminal behavior. Whatever 21-year-old Ron LeFlore was, one thing he wasn't was a seasoned baseball player.

Quite possibly the most incredible part of his story is that Ron LeFlore had never played an organized game of baseball in his life — until he went to prison.

"We had a little team in our neighborhood, we'd go up to the park to play, but that was about it," he says. "No Little League, nothing organized or official."

Ron LeFlore had never played an organized game of baseball in his life — until he went to prison.

tweet this

Fortunately for LeFlore, the prison system had a baseball program, and a fellow inmate, Jimmy Karalla, watched him play. Karalla was an associate of revered tavern owner Jimmy Butsicaris, proprietor of the Lindell A.C., widely hailed as America's first sports bar (which is now the subject of an ongoing exhibit at the Detroit Historical Museum).

In April of 1973, Karalla wrote a letter to Butsicaris detailing LeFlore's prison-yard baseball exploits. Butsicaris, a close friend of Tigers manager Billy Martin, cajoled the fiery skipper, who as an ex-player himself was skeptical that he could find a serviceable player behind bars.

As Butsicaris' daughter, Liz Butsicaris Jackson, remembers, "[Karalla] kept calling my father, and my father said to Billy, 'C'mon, let's do this, let's do this. What have you got to lose?' and finally got Billy to go."

On May 23, 1973, Martin and Butsicaris organized a "goodwill trip" to Jackson state prison, which included Tigers slugger Frank Howard and Hall of Fame broadcaster Ernie Harwell, though the film doesn't depict either man as being there. Martin and Butsicaris portray themselves in the movie, with Butsicaris getting a solid A for his believability and smooth delivery, while Martin comes off as a famous guy who was offered a role for his name recognition.

But the film's portrayal of a sodden field unsuitable for a major-league workout is spot-on, says LeFlore.

"I was disappointed I didn't get to work out [that day]," he says. "I was like a Jim Thorpe of that prison. Played basketball, ran on a relay team, played softball, baseball, lifted, whatever I could do." Despite not being able to showcase his skills that fateful day in Jackson, based on Karalla's recommendation and the testimony of other prisoners Martin met during his visit, the Tigers manager promised LeFlore a tryout when he was paroled. LeFlore didn't dismiss it as idle talk.

"Frank Howard gave me a bat," LeFlore says. "It was the longest bat I'd ever seen. I hit balls with that thing until the skin was falling off my fingers. Didn't have batting gloves, [but] the pain was meaningless to me. I was gonna be prepared for that tryout."

He's also grateful to the man who put the whole thing in motion.

"If it wasn't for [Jimmy] Karalla, I never would've had a baseball career," he says.

In July of 1973, the Tigers were able to sign him to a contract that seemed to fast-track his parole.

"Jimmy was really good friends with Wayne County prosecutor (William) Cahalan. I don't know if he pulled any strings but ..." says Butsicaris' son-in-law and former Lindell A.C. employee David Jackson, hinting that he believes that may have been the case.

The film, a classic late-'70s style TV movie, heavy on the melodramatic soundtrack flourishes and timed-for-commercial-break edits, is based on the book Breakout: From Prison to the Big Leagues written by LeFlore and longtime Detroit Free Press and Oakland Press sports scribe Jim Hawkins. (Side note: One in a Million screenwriter Stanford Whitmore wrote three episodes of the popular '60s television drama The Fugitive.) It doesn't depict any behind-the-scenes machinations. In fact, the film gives the impression that Tigers general manager Jim Campbell was unaware of LeFlore until he set foot inside Tiger Stadium for his tryout. Hawkins, the Freep's Tigers beat writer at the time the LeFlore story started to unfold, recalls how it all went down:

"The first time I heard any mention of [LeFlore] was when I happened to be sitting in Billy Martin's office a few hours before a Friday night game in 1973 when LeFlore called to inform [Billy] he was out of prison on a brief parole and would like to come to Tiger Stadium the following day for the tryout he had been promised when Billy met him in Jackson prison," Hawkins says. "I'm not sure any of the other reporters covering the team (there were only a few of us in those days before sports talk radio and the internet) were even aware Ron existed at that point. I can't say for certain, but I probably was the only reporter present at Tiger Stadium for Ron's initial workout — and I was only there because I always got to the ballpark early. No one, including the Tigers, had any idea how significant that Saturday morning session would be."

When LeFlore later worked out for the Tigers at Butzel Field on Detroit's west side, he impressed Tigers scout and future general manager Bill Lajoie with his 60-yard dash.

What had started as a favor to Martin's friend Butsicaris resulted in LeFlore a free man on a short trip through the minor leagues (where he played for manager Jim Leyland), culminating in his August 1974 callup.

While it was common knowledge that LeFlore had a sordid past, there was no Twitterverse, no 24-hour news cycle. And he was a local kid, embraced by Tigers fans. "I heard catcalls sometimes, but mostly I heard the chants of 'Go Ron Go,'" he says. "The team depended on me to steal bases." LeFlore thrived.

He had shattered the odds and made the major leagues, eventually making the 1976 American League All-Star team alongside teammates Rusty Staub and Mark "The Bird" Fidrych. His level of success was unprecedented, though his journey from prison to the big leagues wasn't even unique on his team. Fellow Tiger Gates Brown had served time in the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield, Ohio — the prison immortalized in The Shawshank Redemption — prior to his major-league baseball career.

"Gates Brown was someone I spent time with because we came from familiar circumstances," LeFlore says. "He helped me with my batting. I was happy for him when he became hitting coach, and I'm sad to see him gone." (Brown was the Tigers' hitting coach from 1978 to 1984. He died in 2013.)

For Tigers fans, the film version of the tryout is a Mount Rushmore of real-life Tiger greats portraying themselves: Kaline, Cash, Freehan, Northrup, all of whom seem relaxed in front of the camera. Actor Matt Stephens plays Tigers centerfielder Mickey Stanley, the man LeFlore would eventually replace. (Fans of the film Revenge of the Nerds might recognize Larry B. Scott as LeFlore's brother Gerald.)

LeVar Burton, fresh off his Emmy-nominated portrayal of Kunta Kinte in the groundbreaking ABC miniseries Roots, was cast as LeFlore in the film.

"I had seen Roots" says LeFlore, "so I was excited, but he seemed awfully small to be playing me. They got a guy from Wayne State to do the baserunning and some of the batting scenes."

One one occasion, Burton overslept in his hotel room on a shoot day at old Tiger Stadium.

"It scared me," LeFlore remembers. "We had a (real) game that night."

Some of LeFlore's own behavior scared the Tigers a bit.

"My dad kept a close eye on him," says Butsicaris Jackson "My dad had enough street sense to know that where he came from, he could [end up] back there really easily."

(Butsicaris' own life was made into the movie Jimmy B and Andre, starring Alex Karras. Karras later bastardized the tale for the TV series Webster. In One in a Million, Madge Sinclair plays LeFlore's mother; coincidentally, she also plays Andre's mother in the Butsicaris biopic.)

Despite LeFlore's on-field success and fan adoration, he was abruptly traded to the Montreal Expos in December of 1979 for pitcher Dan Schatzeder.

It was rumored then and the rumors persist today that the trade was precipitated by LeFlore being seen in the company of alleged mobster Frank Usher, better known on the streets as Big Frank Nitti. Usher was charged with a 1979 triple beheading, convicted, but ultimately acquitted on appeal.

"I was disappointed to be traded," says LeFlore of the deal that outraged Tigers fans.

While Schatzeder had a subpar year for the Tigers in 1980, losing 13 games, LeFlore stole 97 bases for the Expos to lead the National League.

But it will be LeFlore's glory years in Detroit that will be celebrated Sunday at the Detroit Historical Museum, which is already celebrating the now defunct bar that gave rise to LeFlore's unlikely legend.

"We're gonna do a meet and greet, and talk. Whatever they want me to do, I'm willing," says LeFlore,who now resides in Florida with his wife, Emily.

Butsicaris Jackson was an extra in One in a Million. She is now the proprietor of Grosse Pointe-based Queen of Cups Catering, and was once the personal chef to the New Kids on the Block. She is no stranger to celebrity, but looks forward to LeFlore's appearance in Detroit.

"It will be good to see Ronnie and give him a hug."

On in a Million: The Ron LeFlore Story will be celebrated with a 40th-anniversary screening starting at 2 p.m. on Sunday, Aug. 18 at the Detroit Historical Museum, 5401 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-833-7935; detroithistorical.org. No cover.

Get our top picks for the best events in Detroit every Thursday morning. Sign up for our events newsletter.