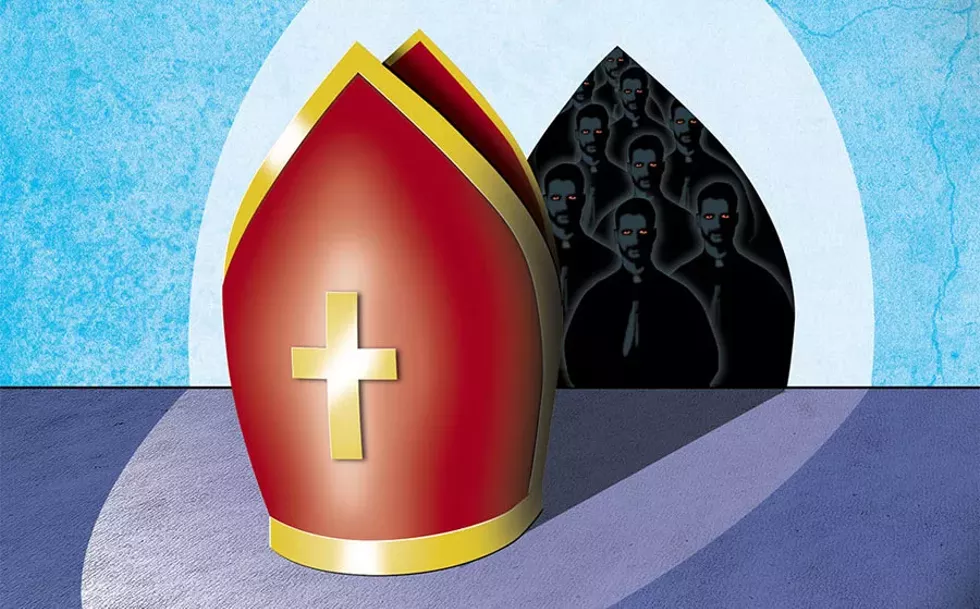

While the local Catholic Church promotes its efforts to protect children today, it's been busy protecting its financial assets as a day of fuller reckoning for past sexual abuse survivors draws closer. Across the country, statute of limitations laws on civil actions have been eroding, leading to costly settlements for abuse victims. Only intense lobbying by the insurance industry and the Catholic Church has restrained this tide in Michigan.

But now, one determined survivor of an alleged assault by a priest decades ago wants the state legislature to open a window for claims to be filed for clerical misconduct, similar to what it enacted last year for many victims of Larry Nassar, the former USA Gymnastics and Michigan State University doctor.

"How can they justify doing this for Nassar's victims but not for those of us victimized by priests?" asks the survivor, who wants to remain anonymous for this article.

In 2012, after a lifetime of trauma and therapy, the survivor finally told church officials in another Michigan diocese of the incident, which dates to the 1960s — but says the local bishop has done nothing tangible since then beyond offering sympathy.

But as Marci Hamilton, director of the victims advocacy group Child USA, says, "They can — and they must."

Archdiocese of Detroit spokesman Ned McGrath has said that the archdiocese has paid a total of $4.5 million to abuse victims. Nationwide, the church has paid out an estimated $3 billion to $4 billion (with the higher figure calculated in a National Catholic Reporter study last year). Twenty-one dioceses and religious orders nationwide have gone bankrupt as a consequence of the scandal, according to watchdog group Bishop Accountability. The Archdiocese of Detroit has 1.6 percent of the nation's Catholics (1.16 million out of 70.4 million) but has paid little more than 0.1 percent of the total abuse settlements. Either there have been 10 times more abusers elsewhere — which seems unlikely — or the local church has had outstanding lawyers. For decades, it's offered small settlements to clerical abuse survivors, often in exchange for non-disclosure agreements (like the one I reported in a Deadline Detroit story earlier this year about Sister Mary Finn).

"The church always starts out with a paltry offer," says Western Michigan University professor of accountancy Jack Ruhl, an expert on church finances in the state and the husband of a survivor of priest abuse. Ruhl points out many examples of creative fiscal maneuvers by Catholic authorities. All Michigan dioceses (and most others nationwide) now post financial statements online, "but 99 percent of the time," he says, the accounting is for only the chancery — the administrative offices — while the lion's share of church assets in parishes, cemeteries, and seminaries are excluded. That makes it nearly impossible, Ruhl says, to know the true amount of church wealth.

In 2007 in Milwaukee, then-archbishop Timothy Dolan transferred $57 million in diocesan money to a cemetery trust fund. The archdiocese of Detroit has been equally bold in hiding its wealth. In December, it transferred most of its physical properties — including parish churches and buildings — to a separate corporate entity, Mooney Realty. "They did it to hide their assets," says Ruhl, and make it harder for victims to collect compensation in civil suits. Indeed, the archdiocese of Detroit's latest financial statement posted online does exclude "parishes, schools and cemeteries," plus "hospitals, St. John's – Plymouth, Sacred Heart Major Seminary," and "Mooney Real Estate Holdings."

And in a remarkable and little-known piece of gerrymandering, the Archdiocese of Detroit has even absorbed the Cayman Islands into its jurisdiction.

When I visited Fr. Mike Molnar in the rectory of Sacred Heart Parish on Grosse Ile earlier this year, he seemed well prepared to portray the Cayman venture in a favorable light. He maintains the Caymans were really more like a mission than a part of the archdiocese. If St. Ignatius, the parish there, could ever get enough of its own Caribbean priests to staff its churches, Detroit would let it go, he contends.

Molnar spent eight years running St. Ignatius before moving to his present post on Grosse Ile. How did he get such plum assignments? "I grew up on Algonac. I like being near the water," he laughs.

His initial assignment came right from the top. In 2000 Msgr. John Zenz, Cardinal Adam Maida's right-hand man, told Molnar that Maida wanted him in the Caymans.

The Vatican likes major archdioceses to administer missions, and Molnar says Jamaica wanted to stop running the parish in the Caymans. New York also wanted it, but Rome put Detroit in charge — in part, he says, because Detroit had just relinquished its longstanding mission in Recife, Brazil. When I suggest that perhaps Detroit got the prize because Maida had connections to Rome, Molnar allows that might have been the case.

Molnar was supposed to rotate out after five years, but Hurricane Ivan interrupted those plans in 2004. Most of Grand Cayman flooded, but the school and church were luckily on higher ground. Molnar stayed to help rebuild.

Molnar says there are two churches on Grand Cayman and one the Archdiocese of Detroit built for $900,000 on Cayman Brac, 90 miles away. The priests fly to Cayman Brac monthly and consecrate enough hosts for a month's worth of communions. Pallottine priests from India assist priests from Detroit. The parochial school has about 700 kids, and there are about 800 families in the parish.

The archdiocese of Detroit has 1.6 percent of the nation’s Catholics, but has paid little more than 0.1 percent of the total abuse settlements. Either there have been 10 times more abusers elsewhere, or the local church has had outstanding lawyers.

tweet this

When I turn the conversation to the Caymans' reputation, Molnar says that a lot of wealthy people live at least part of the year in the parish, including members of the family of the late financier Ernest Olde. There aren't a lot of poor folks in St. Ignatius — "we hardly ever gave out any food" to anyone, Molnar admits.

Molnar says Maida visited the islands at the beginning to "sign documents" and a couple times for confirmations. His successor, Archbishop Allen Vigneron, visited in 2011 for the dedication of the church on Cayman Brac.

In 2014, Vigneron celebrated mass in the Caymans as part of the ceremonies marking the opening of Health City, a hospital the Detroit church helped fund that specializes in cardiac surgery, cardiology, and orthopedics. Health City is a joint venture of the Catholic system Ascension Health and Narayana Health of India.

I mention a complaint I'd seen online that said in the Caymans, Molnar "spent too much time on finances." His reply: "I didn't spend any more time on finances there than I do here." He says in both assignments he's watched over parish money and sent any surplus to the archdiocese. Despite the islands' reputation and history, the archdiocese isn't hiding or laundering money in the Caymans, he says.

The archdiocese of Detroit has always had wealthy benefactors like Tom Monaghan and others — who comprise a "Cardinals' Club" of millionaire donors. It's had magnificent and extensive physical assets, and plenty of the faithful filling collection baskets every Sunday. Its wealth may have reached its zenith under Maida — but the cardinal's financial dealings were controversial.

When Maida was still a bishop of Green Bay in the 1980s, he proposed the idea of building a "John Paul II Center" to honor the reformist pope. Some observers thought that project helped him become a cardinal.

The center opened in Washington, D.C., in 2001. It was supposed to be a combined tourist attraction and think tank. The Detroit archdiocese helped finance the $75 million cost with a loan from an Irish bank to the tune of $54 million. The John Paul II Center never succeeded, and it was sold to the Knights of Columbus in 2012 for $22.7 million.

Because of the project, three Detroit priests were so concerned that the archdiocese was putting their pension funds at risk that they filed suit against the chancery, seeking full disclosure of church assets. After a long court fight, in 2015, an appeals court ruled against them.

Maida retired in 2009. As part of his master plan to remake the shuttered St. John's Seminary in Plymouth into a luxury hotel and wedding and banquet venue — a multimillion makeover thought to be financed by church benefactor and wealthy builder William Pulte, who died last year — Maida built himself a luxury condo there. At age 89, that's where he is still living when he's not visiting the Caymans.

Maida does have strong connections to Rome and to church finances — he was one of six prelates on the board of directors of the Vatican bank during its financial crisis that led to the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI in 2013.

The church also has had powerful friends in Lansing. Last year, Hamilton, of Child USA, testified during hearings on reforming Michigan's statute of limitations law in the wake of the Nassar revelations. She characterizes Michigan's statute as the worst in the nation for abused children — and saw it reflected in ad hominem attacks on her credentials. "It was quite startling," she says. "I got a very chilly reception." In the end, the state Court Reform Association led the way in watering down broader reforms.

Nationwide, it's "been a banner year" for statute of limitations reform, says Hamilton, with 39 states considering changes, and many enacting measures collectively known as Child Victims Acts. Hamilton says she's met with many victims in Michigan who've been "left out in the cold." It's "a very partisan issue," she notes — and with more Democrats now in Lansing, she's hopeful the tide will turn here too.

In May, Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel exploited a loophole in the existing state statute of limitations law to arrest and criminally charge six priests who moved out of state, which stopped the statutory clock from ticking. The cases are in various stages of preliminary hearings in county courts. And the AG's office continues to review hundreds of thousands of documents seized in raids of all seven dioceses in the state last October.

The fact that Nessel is expending great resources on these cases encourages other victims to go public, says David Clohessy, a national leader of SNAP, the Survivors Network for those Abused by Priests. Nessel is even trying to get an 84-year-old priest extradited from India to face charges from more than 50 years ago. Hamilton also applauds Nessel's efforts to "put powerful men on notice."

The clerical abuse survivor who wants a Nassar-type window in Michigan — or something even stronger — has been reimbursed for some out-of-pocket expenses by the church since coming forward, but that's a pittance compared to the crippling amount spent during a lifetime of treatment and medications for PTSD.

As for the welfare of accused priests, a recent AP story revealed that a shadowy Catholic organization named Opus Bono supports them legally and financially. And the Archdiocese of Detroit confirms that if a priest has served enough years to qualify, the archdiocese is not legally permitted to take away his pension even if he is defrocked.

As Western Michigan University's Jack Ruhl contends, "The church never does what's right because it's right, only when it's forced to because of potential liability." That time may soon be at hand if more survivors of past abuses have more opportunities to file civil suits here.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.