A new exhibition in the Detroit Institute of Art's Prints, Drawings, and Photography galleries takes a sprawling look at the many meanings of the notion of home.

Making Home is the first show organized at the museum by Lucy Mensah and Taylor Renee Aldridge, who joined the DIA last year as assistant curators under new hire Laurie Ann Farrell in an effort to rejuvenate the Contemporary Art department.

"We wanted to complicate this notion of home," Aldridge says. "It's a very accessible theme, but we didn't want to just present a whole bunch of works that were predictable."

In that case, mission accomplished. Despite the seemingly simple premise, the show packs plenty of surprises, starting with a dramatic work that is neither a print, drawing, nor photograph: a rarely seen 1979 installation by Detroit artist Charles McGee made of materials reclaimed from abandoned Detroit houses that serves as the exhibition's centerpiece.

"I'm a fan of Charles McGee's work and I didn't know he did work like this," Aldridge admits. "It was really surprising to see he did this installation work and was sort of trying to subvert ruin porn before we were even calling it ruin porn. ... You were starting to feel the effects of the white flight and the mass movement out of the city. It was really sort of prophetic of him to start to interrogate those themes early on."

To create the show the two assistant curators were given free rein of the museum's permanent collection. They say they decided on the idea of the theme of "home" early on after realizing they had both recently read the same books: Yaa Gyasi's Homegoing and Isabel Wilkerson's The Warmth of Other Suns. As two African-American women, they say they were drawn to the stories due to the way in which they explored African diaspora: Homegoing looks at a family that originates in Ghana but is dispersed during the slave trade; meanwhile, the non-fiction saga The Warmth of Other Suns details the Great Migration of African-Americans from the American South to the North in the 20th century.

"Both of the works deal with themes and stories related to the migration, particularly domestic migration, but also a forced migration," Aldridge says. "But you still find a silver lining and a way to make a home, ultimately, out of these oppressed situations."

As the two explored the museum's archives searching for images pertaining to the theme, they found that eight broad categories began to emerge, which they used to organize the show: Urbanization, Displacement, (In)Security, Domesticity, Childhood Imagination, Home and Community, Melancholy, and the Sublime.

The simple premise yields a staggering diversity of works, representing all manner of mediums and locales. There's American artist Jane Hammond's "Chai Wan Four," a composite photo depicting a densely populated Hong Kong apartment building. Figures are interspersed throughout the image, holding toy airplanes — suggesting the conflict of globalization and individuality. A black-and-white print by pop artist Robert Rauschenberg suggests the impending destabilization brought on by suburban sprawl.

Contrast that with Lorna Simpson's "Bathroom" from her Public Sex series, which contains no figures at all — only a showy New York City vanity bathroom mirror. "She wanted to sort of uplift this narrative that is akin to gay men and this cruising culture, and seeking public sex and certain public spaces, and how these spaces become one's home in some ways," Aldridge says. "She was really interested in how these men made the space their own." The piece is accompanied by an amusingly cryptic museum card: "There were five stalls, and in the second stall there were three legs."

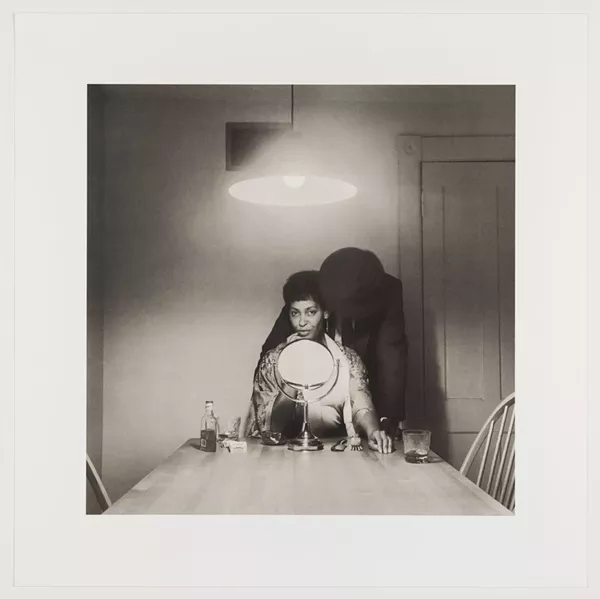

Two of the exhibition's showstoppers are both by photographer Carrie Mae Weems. "The Kitchen Table series" represents one of the museum's latest acquisitions, depicting the artist photographed around a kitchen table, engaged in all manners of activities that that part of the home invites: playing solitaire, quarreling, and making up with a lover.

A multidisciplinary artist, Weems' work is accompanied by blocks of prose. "When you're presented with these images you think they speak toward traditional ideals and representations of domesticity, but then you're presented with the text that supports this idea on nonmonogamy and focusing on the self," Aldridge says. "I think it's a really honest exploration into centering oneself in a domestic space and not trying to satisfy these ideals that have been placed on women for so long."

Another Weems work, titled "Grabbing, Snatching, Blink and You Be Gone," finds the artist inside of a slave dungeon in Senegal. Her stark black-and-white images flank a text-based silkscreen of the work's title, which has a disorienting postmodern effect that calls to mind the jarring intertitles of, say, a Jean-Luc Godard film.

"She took a trip to see this slave castle and her experience of actually dwelling in the slave dungeon propelled her to want to capture for the viewer what it must have been like for an enslaved African to be taken violently from their home and put in these dungeons," Mensah says. "I think for the viewer you're put in that situation of what it would look like and what it would have felt like to be disoriented and taken from your home and put in this dark, mysterious, filthy place."

In a similar vein, Roger Shimomura's lithograph print "American Guardian," offers a view of a Japanese-American internment camp. It's a decidedly un-homely scene, featuring barbed-wire fence and a soldier atop a panopticon, looking down ominously at a child riding a tricycle.

Contrast that with a photo by Carlos Diaz of a front yard of a presumably Latino household in Southwest Detroit, which is hung right next to the Shimomura's image and echoes some of its visual elements — a tricycle, a fence. Together, the images conjure ideas about immigration, security, and privacy — issues which have become front and center in the age of President Donald Trump.

Images of and inspired by Detroit serve as a through line across the exhibition. Aldridge says that was by design.

"I'm from here, so I'm bringing a specific focus on all of the changes that are happening here, and also having a lot more sensitivity around it," Aldridge says. "Of course, it's hyper-local, but I also have experiences being in other locales, and there are similar sort of changes happening in these major cities simultaneously. So how can we bring Detroit into that conversation, and vice versa?"

The Detroit images are among the exhibition's strongest. A photo from the late Bill Rauhauser depicts a seemingly abandoned house in a field, its windows blown out — creating a composition and sense of unease reminiscent of Andrew Wyeth's iconic "Christina's World." According to the photo's title card, the house is located near Detroit — a reminder of the shrinking city's urban and occasionally seemingly rural characteristics.

("I think of this group of work as representing Alfred Hitchcock films. Lucy was especially drawn to all of these works, but they creep me out," Aldridge laughs. "But I'm happy that they're in the show!")

But home is where the heart is, and the show finds beauty in the decay. Another of the exhibition's most striking images is a large 2009 photo by Andrew Moore, depicting a real-life makeshift dwelling inside of an abandoned warehouse — a home of the homeless. While no figure is present, all the signs of life are there. A fire burns. Clothes hang on a line. A shopping cart is filled with cereal boxes. A draped sunlit tarp adds an aura of serenity to the scene. (As the title card points out, the building now houses the Outdoor Adventure Center recreational park.)

"For this particular theme we were looking at how do people make homes out of no home? How do they contend with a transient life?" Mensah says. "It's a beautiful image of human existence — the compulsion to try and make do with whatever you have."

Making Home is currently on view at the Detroit Institute of Arts; 5200 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-833-7900; dia.org; free with museum admission, which is free for residents of Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb counties; runs through June 6, 2018.