Treasure Jackson, who lives in the city’s northwest corner, had heard bits and pieces about Detroit’s right to counsel ordinance from a mix of news reports and word of mouth. But because the city had done such a poor job implementing and publicizing the ordinance she was confused about what it meant for her situation.

She knew she was facing “something unjust” when the owner of the Four Corners apartment building started eviction proceedings against her for nonpayment, despite attempts to pay down her balance.

Stressed from clocking nearly 60 hours a week for a security gig while raising a teenage son and supporting a disabled father, Jackson’s “mind went bonkers,” she says. She reached out to Detroit Eviction Defense (DED), a coalition of residents “united in the struggle against foreclosure and eviction” for whatever clarity they could offer, and perhaps a roadmap of what was to come.

Luckily, Jackson already knew about DED because they’d been ringing the alarm about the shockingly bad conditions at Four Corners apartment building for about a year.

And as she puts it, “I like a good fight. … If I feel like something is unjust, I’m gonna speak up.”

Her looming eviction isn’t the only part of this that’s unjust, though. It’s also the way the eviction was being done. Back in May, City Council unanimously approved a right to counsel ordinance after significant public pressure. The idea is simple: lower-income tenants shouldn’t be left alone to defend themselves against powerful landlords whose attorneys specialize in ejecting people from homes. On Oct. 1, the city was supposed to start providing lawyers for those tenants for free.

But because the city blew past that deadline, Jackson’s fight is massively more difficult than it should be. And she isn’t alone. More than 4,000 households have faced eviction since that deadline passed. Based on a recent University of Michigan Poverty Solutions report, only one in five of these tenants will have had representation if recent trends hold.

Right to counsel ordinances are stunningly good at keeping people in their homes. Cities across the country are waking up to the idea that sending sheriffs to drive entire families from the only shelter they have is preventable. Cities like New York City, Philadelphia, Newark, Baltimore, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Denver, San Francisco, and others have all passed right to counsel ordinances.

It’s hard to miss the cruelty of what’s happening here. The City of Detroit is letting thousands of evictions take place. The overwhelming majority of those people likely have no attorney. Because of this, tenants are considerably more likely to be tossed out on the street — exactly what the right to counsel ordinance was designed to prevent. An ordinance the city had months to implement.

For housing justice advocates, this is just one chapter in a terrible century-long story of the real estate industry exploiting Detroit’s majority Black renter population. It also exposes the story of citywide revival as a myth with enormous holes. As corporate money floods the city and multiplies itself among the already rich, it is also feeding racial and economic inequality. In Detroit, as in countless cities across the country, real estate has been the primary engine for both of these.

To understand right to counsel, and why supporters see eviction as intolerable in the first place, it’s important to first understand homeownership in the city, and how government-sponsored segregation and private real estate greed destroyed any chance of widespread Black prosperity here.

Throughout much of the 20th century, the ghetto was national policy. After World War II, white communities got a beautiful welfare state in the form of generous mortgage support. Meanwhile, Black communities got taxation without representation, paying their share without the benefits. When it came to housing, this amounted to a massive heist of Black wealth as families were boxed out of homeownership’s wealth-building potential and locked into crumbling slums.

As one advocate put it in a 1973 Congressional testimony, poor and working-class Black families had “no other choice, no other place to go.” This was obviously a nightmare for those families, but it was great for business. Keanaga Yamahtta-Taylor writes about this in Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. Pinned into the ghetto, private developers, realtors, and bankers could freely exploit Black families for a profit. This advantage was ruthlessly enforced. If a realtor threatened their business model by breaking the color line, industry bosses would crush them because there was just too much money to be made in charging desperate Black families absurd prices for nearly unlivable housing. Despite this, Detroit became a majority homeowner city until very recently.

But the heist never stopped. The same Black neighborhoods that were looted by the real estate industry in the 20th century became the infamous “subprime” neighborhoods of the early 2000s, when bank loan officers joked openly about tricking “mud people” into “ghetto loans.”

This was a nightmare for places like Detroit. Since 2008, one-third of properties have been foreclosed, including one in four between 2011 and 2015 for failing to pay “systematically and illegally inflated” property tax bills, totaling about 100,000 homes.

Over this period, more and more Detroiters became renters, (300,000 in total) putting them at the mercy of landlords and management companies whose top priority is profit, not housing people. (According to the latest census data, a narrow majority of Detroiters now own the home they live in, reversing a decade-long trend toward renters.) In order to illustrate the human crisis eviction represents and who’s getting paid off it, the Urban Praxis Workshop developed “the Eviction Machine” to expose how running people out of homes is an important business model for the real estate industry in Detroit.

It isn’t hard to see how this could go wrong. If your business model depends on profiting from shelter, a human need, then it will quickly clash with Detroit’s largely Black and working-class population struggling to make ends meet in order to fulfill that need.

Here’s what we know: A third of Detroiters live in poverty. While the city recently reported a 6.8% unemployment rate, the rate for Black residents is likely much higher. In recent years, 35% of low-income Detroiters say their financial situation has gotten worse. So it’s no surprise that, according to the American Community Survey, 60% of Detroit renters were cost-burdened in 2021, meaning they spend more than 30% of their income on housing. A shocking 34% spend more than half of their income on housing and are considered severely cost-burdened. This has hideous ripple effects. Nearly 40% of Detroit’s families don’t have enough food to eat. The same amount can’t afford a $400 emergency.

What does all this mean for evictions? According to the Poverty Solutions report, “21% of renters (61,000 tenants) will face the threat of eviction this year.” Landlords, as they will remind you, do not have to weigh history’s sins when they move to raise rents or evict someone. But anyone who looks honestly at the history of housing in this city will see that evictions can’t be untied from the chain of profit-maximizing decisions above — decisions that are still ruining lives to this day.

As public outrage and pressure mounted, City Council President Mary Sheffield and the Detroit right to counsel coalition stepped in to craft a right to counsel ordinance. It passed unanimously back in May, promising that low-income people wouldn’t have to face experienced landlords and their attorneys alone. According to another Poverty Solutions report, “only 4.8% of tenants were represented by an attorney in eviction cases filed 2014-2018, compared to 83.2% of landlords.”

Unsurprisingly, landlords win the overwhelming majority of these cases. And as research shows, having an attorney of your own greatly improves your odds of winning in court and keeping your home. That makes the right to counsel an important outlet for people who desperately need good representation. But its delay, and our national decision to make housing a luxury good instead of a human right, means that we remain shackled to the recent past, when so many had “no other choice, no other place to go.”

The Four Corners would’ve been considered a slum fifty years ago. In Race for Profit, Keanaga Yamahtta-Taylor cites a Free Press article from 1972, in which one eastsider describes appalling living conditions, from “rat infestation to holes in the ceiling.” Today, nearly 100,000 Detroiters live in unfit housing.

At the Four Corners, entire stretches of the hallway have had the carpet pulled up, exposing a floor that’s badly scarred from what looks like extensive water damage. Inside the apartment of Ken Pruitt, another tenant and a close friend of Treasure’s, they describe life there as one where residents are forced to navigate constant disrepair. Doors and closets take more effort to close than they should because the carpet is ballooning from what appears to be previous water damage. The tops of nail heads spring from a kitchen floor where the carpet’s been pulled out. Black mold lines the bathroom floor and the splatter of bed bugs line the bedroom wall. Days later, Treasure sends me a photo with a text message saying “I flushed the toilet and it came through the tub this morning.”

These are normal conditions at Four Corners. Nearly a year ago, Detroit Eviction Defense put the building’s owner, Michael Eissman, on their “Slumlord Watch,” after tenants reached a breaking point and began documenting all the ways Four Corners fails and devalues its residents: “roaches, black mold, sewage leaks, broken windows, inadequate heat, and repeat flooding.” DED notified the city, but progress has been slow.

For a moment, though, Treasure was optimistic. Both her and Ken take pride in their homes, and all they’ve done to make them livable despite the owner’s extraordinary negligence. Throughout a good chunk of her two years there, the building’s new management — represented by a woman who Treasure says would at least hear her out — seemed to be slowly turning a corner. They seemed to be listening to tenants and made some badly needed repairs. On top of that, one of the building managers had a kind heart, Treasure says, and would work with tenants whose circumstances were complicated but navigable. For Treasure, that meant paying rent toward the end of the month to better match her pay period.

But then a backlash came. The manager who understood Treasure’s situation was replaced with someone who began to tighten the screws again. Repairs slowed down and verbal agreements like the one made with Treasure were thrown out. Treasure picks up any work shift she can, often overnight, and regularly clocks close to 60 hours a week. She supports a teenage son and a disabled father, and is saving up for a home of her own.

Black mold lines the bathroom floor. Days later, Treasure sends me a photo with a text message saying “I flushed the toilet and it came through the tub this morning.”

tweet this

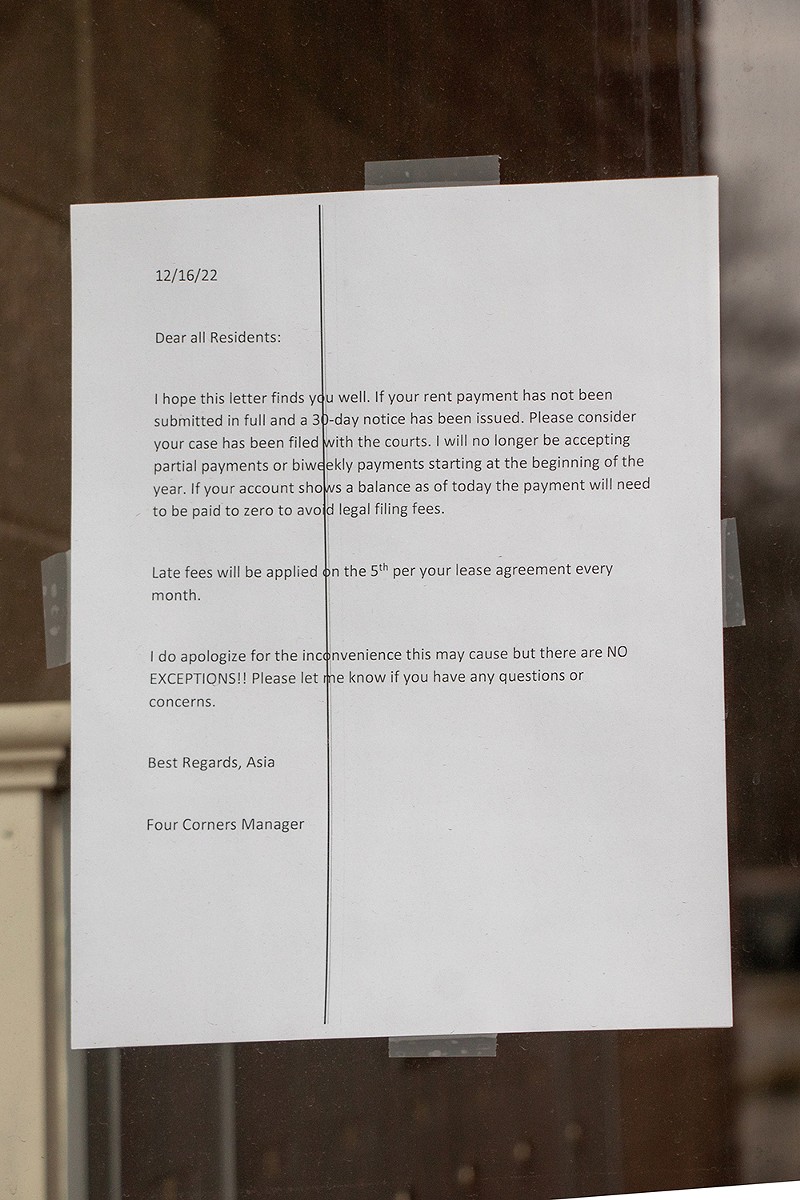

When she fell behind on rent this fall, the new management refused to take her partial payments and told her she was “blocked and never called me back.” Soon after, Jackson was handed a notice to quit, which gives tenants thirty days to leave on their own. When that day came on Dec. 12, she declined, something she had every right to do. The landlord must now take her to court if they want to proceed. Which is exactly what they’ll have to do, she says.

Things might’ve been different if the more understanding manager were still there, and Jackson suspects that’s exactly why she was let go: “She was too nice,” which in this case means “she was putting money towards helping clean the place up and get rid of insects.” Without warning, Jackson went from feeling like she had a partner to work with to being run out by a cutthroat slumlord. “You really miss that atmosphere of a person who’s willing to work with you,” she says. Attempts to contact Eissman for comment were unsuccessful.

Changing gears so abruptly and then being hit with an eviction could have been a deeply isolating experience for Jackson. Eviction, by its very nature, boots people from the main arena, outside of the workplace, that most people’s lives unfold in, cutting them off from loved ones and entire communities in the process.

But Jackson began connecting the dots between what she was facing and the problems with the entire rental market. She realized that although “this is my fight, it’s not only my fight.” By that, she means the challenge of finding good, affordable housing affects people in every corner of the city. Those people should be uniting against “money hungry” landlords to “prevent this from happening to anybody else.”

Here’s the thing though: because so many people are facing an almost identical landscape of grief in the rental market and bullying, neglect, and retaliation from landlords, the actual solution “is not complicated,” Attorney Tonya Myers Phillips, project leader of the Detroit right to counsel Coalition (DRTC), tells Metro Times.

Right to counsel isn’t a perfect tool, especially in a court system that’s notoriously cozy with landlords and real estate sharks, but Jackson’s situation is exactly the type of thing an aggressive eviction defense office could prevent by giving her a fighting chance against powerful and relentless adversaries.

“It’s inexcusable that the mayor’s office let this deadline pass in the manner that they did,” Phillips says. “We’re calling on our mayor to fully fund the ordinance so our people, our community won’t be unnecessarily evicted and facing homelessness.”

She adds, “We’re past the point of asking questions about, ‘Does this work? Should we do this?’”

According to eviction defense experts, a serious right to counsel program in Detroit would cost roughly $16.7 million annually. The Detroit Right to Counsel Coalition is calling for a round $18 million annually to ensure the office has everything it needs to fight aggressively on behalf of tenants who need it. So far, the City Council has approved $18 million over three years, while the mayor has so far only allocated $6 million over those three years, coming up $48 million short of the amount advocates say is needed to do this the right way.

“So the ordinance is dramatically underfunded,” attorney Phillips says. Which is inexcusable since “Detroit is in an incredibly strong financial position. The money’s not an issue.” Phillips points to $800 million in American Rescue Plan funding for Detroit, which came with strong Treasury Department encouragement “to support the right to counsel and eviction diversion strategies.” More to the point, a recent Rocket Community Fund report found that a well-funded right to counsel office would save the city $18.9 million annually by freeing up all the money that’s spent on the sprawling eviction industry: from carrying out evictions to funding the meager safety net programs that support people afterwards. In other words, the program would pay for itself and then some.

The report also found that “represented tenants are nearly 18 times more likely to avoid disruptive displacement than unrepresented tenants.” That’s astoundingly effective, and makes it all the more disturbing to know that “individuals are suffering unnecessarily,” Phillips says.

After missing the deadline and following public outcry, Conrad L. Mallett, the city’s Corporation Counsel, “accepted full responsibility for the fact that we missed the deadline.” Nearly seven weeks after that deadline, the city finally chose the United Community Housing Coalition to manage the eviction defense office, beginning in early 2023.

When asked about why the city hasn’t imposed an eviction moratorium, Mallet gave two justifications. The first, Mallett says, is that under the federal and state funded Covid Emergency Rental Assistance (CERA) program, “Persons who experience eviction and who come to court with their eviction notice receive representation.” But people familiar with the actual design of that program say this is nonsense. As it stands, tenants who come to court for eviction cases are offered legal advice in a sideroom, but are not given an attorney with the ability to argue forcefully on their behalf. This is perhaps better than nothing, but it is significantly less than what was promised and what the scale of the problem requires.

The second reason is that since “RTC will be up and running by January,” city housing analysts decided “a citywide moratorium at this time was not necessary” though “the possibility of course is always under review.” It’s important to spell out exactly what this means: that tenants should trust the same city that missed its own deadline when it says free eviction defense is coming sometime in January. And according to recent reporting from Malachi Barrett at Bridge Detroit, it will take the city at least until February. In the meantime, thousands of renters have likely already been evicted in violation of the ordinance. Not only that, though — countless more, Treasure Jackson among them, could be next because the city refuses to use the power it has to stop them from being tossed out of homes across the city.

Ultimately, housing advocates say the right to counsel is a narrow solution to a fundamental problem with the way we provide housing in our society, which is mostly through private markets and landlords whose sole purpose is not to offer people quality, secure shelter, but to get paid off of their need for it. Since the stakes are so high though, victories like right to counsel have to be constantly guarded and seen as a step towards the kind of society where housing is a human right.

In response to the city’s delays, Detroit Eviction Defense is urging tenants facing eviction to “ask the court to adjourn (postpone) your case until you are assigned a free attorney under the right to counsel Ordinance.” They’ve spelled out instructions for how to do so, including a sample motion, which you can find online (https://bit.ly/3CEmFej).

The entire saga is also a wake up call for the future of right to counsel. From the very beginning, everyday people have been in the driver's seat, dedicating themselves to getting tenants the support they need and organizing relentlessly for it. Without them, RTC doesn’t stand a chance. “It takes the power of the people to loosen things up and to get action,” Phillips says. And that's what Detroiters have done. And that's what we're going to continue to do.”

This story was made possible through a partnership with the Race and Justice Reporting Initiative and the Detroit Equity Action Lab at the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights.

Coming soon: Metro Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting Detroit stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter