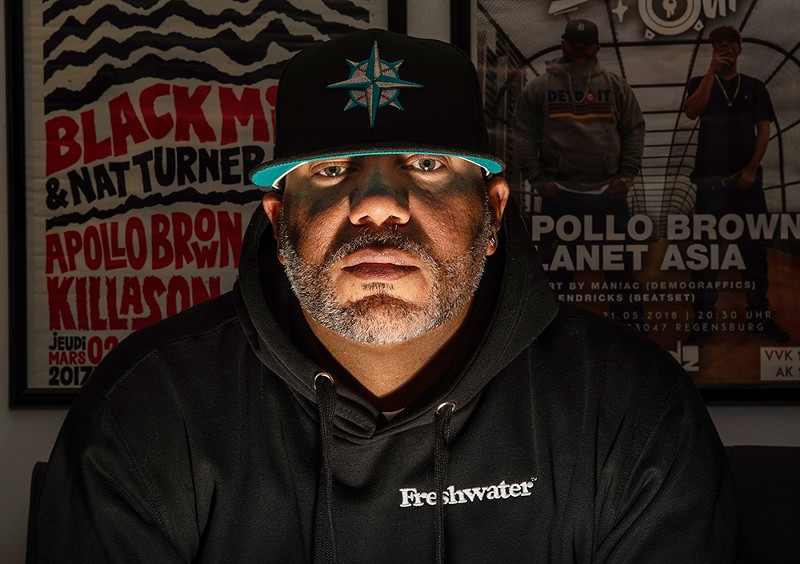

Apollo Brown’s studio might be one of the most sleek and organized creative spaces in southeast Michigan. A computer sits on a desk surrounded by four speakers and a few production instruments and tools. His framed concert posters all hang on walls above bookshelves full of records, diecast cars, and a few slices of hip-hop memorabilia. The floor is carpeted, and all the furniture is black.

“I told my wife if I die tomorrow, burn this room,” he says. “Burn all that equipment, my external hard drives. I got five computers, iMacs with music on it — burn that shit. I don’t want that music out. If it’s not out right now, I don’t want it out.”

Over the last 15 years Apollo Brown has been one of the most consistent producers in and outside Detroit. He’s produced 30 full-length albums (which all hang framed above a black couch) and a litany of singles and album cuts for artists across the globe. He’s a self-described “revolver” because he exclusively and unapologetically makes ’90s-inspired boom bap beats. Where his producer counterparts have evolved into trap, alternative hip-hop, and other experimental sounds, Brown has stayed in one sonic lane. This has made Brown an outlier, a throwback — but also a hero.

Born Erik Stephens, Apollo Brown grew up in Grand Rapids within a plethora of musical influences.

“My mom is white and my dad is Black, so they listened to different types of music,” he says. “I always tell people that one day I could be listening to the Isley Brothers version of ‘Summer Breeze,’ the next day I might be listening to the Seals & Crofts version of ‘Summer Breeze,’” Brown says with a laugh.

Once Brown got into hip-hop he was heavily influenced by east coast acts like Wu-Tang, Mobb Deep, Gang Starr, Nas, and producers like Pete Rock and DJ Premier. He never learned to play any instruments, but had an inquisitive nature when it came to sounds. “I would always dissect the music, I would always listen to one part over and over,” he says.

By age 16 he was experimenting with his own hand as a producer. “It was some of the worst beats ever,” he says, shaking his head. “Me and Bronze Nazareth, we bought ourselves software called Voyetra, it came with Windows 95. This was around 1996. It was a sound manipulation program. We would mess with that. We wanted to rap, we wanted to make music.”

Brown enrolled in Michigan State University, where he spent more time making beats in his dorm room than breaking down math equations in class. After obtaining his bachelors in business administration he moved to Detroit, got a steady job, and became more of a closet producer.

“Ten or twelve [years] went by before I showed my beats to anyone,” he says.

In 2007 he met Detroit emcee extraordinaire Finale, who ushered him onto the Detroit rap scene. “I didn’t realize there was an underground scene or a fan base for the kind of music I was making,” Brown says.

“I encouraged him to work with more local artists and jump in the beat battles to crack some heads and get known,” says friend and frequent collaborator Finale.

The mid-2000s were pivotal years for Detroit hip-hop. The city was reeling from the 2006 death of J Dilla, who represented the largest slice of what many felt was the quintessential Detroit sound. Helluva’s “basement sound” that would go on to take over the world was still in its infancy. The city still had a plethora of talented producers like DJ Butter, Black Milk, Waajeed, Ta’Raach, and Denaun Porter (just to name a few). The proverbial baton had been passed and Detroit hip-hop artists stepped up to the plate.

“Yea we had no choice but to take the torch and run with it … it became an obligation for some and an obsession for others,” says emcee Finale.

Later on that year Brown entered a producer showcase hosted by DJ House Shoes. Brown was still unknown to Detroit’s hip-hop scene, so there were no real expectations as the showcase featured notables DJ Dez and Nick Speed. Each producer had 15 minutes to display their arsenal, and Brown left a shocked room full of dropped jaws buzzing eardrums after he concluded his set. Even he was astonished at the reactions.

“People were coming up to me left and right telling me how my beats were fire,” he says.

Brown took the momentum and started doing more showcases and beat battles. “I was just trying to make the hardest, craziest beats I could make … I didn’t realize there were people were sitting back waiting for a sound like mine,” he says

By year's end he released his first album, Skilled Trade. “It was just a little janky album I put out myself,” he says. “I just wanted to put something out. I hate it to this day. It was a bunch of unfinished stuff.”

Brown’s name and skills grew, but being a producer wasn’t paying his rent. He decided to take a job in Cleveland as a city inspector and commuted to Detroit on the weekends to participate and beat battles and link up with other artists. By 2010 he had reached a crossroads.

“The first week of the year I got laid off,” he says. “Two days later Michael Tolle from Mello Music Group called and told me he wanted to bring me aboard and give me a production contract.”

“Mike from Mello hit me about him and so many others,” says Finale. “And I told them like I’ll still tell them, ‘Y’all better lock in with him because this one is special.’ I’m so proud of my brother.”

Mello Music Group is an Arizona-based boutique record label founded by Tolle in 2007 that looked to bring more boom bap, soul, and a rigid underground sound back to the forefront of hip-hop. A combination of hip-hop becoming more commercialized and the rise of southern trap began to take attention away from east coast legacy acts and emerging artists who preferred a ’90s backpack sound. Fledgling labels like Rawkus and Loud who had rosters that included Mos Def, Mobb Deep, Pete Rock, and Talib Kweli were all defunct. This resulted in smaller labels like Grieslda, It’s a Wonder World Music Group, and Stones Throw Records (which J Dilla was signed to) looking to fill the void.

Though skeptical, Brown understood that signing to Mello was an opportunity to make the kind of music he wanted to make and get paid for it. “The only people on the roster then was Kenn Starr and Oddisee,” Brown says. “I decided to give it a year to see if it would work. And if my bank account didn’t reflect what I wanted it to reflect, if my reputation didn’t reflect what I wanted it to, then I would just update my resume and go back to work.”

Brown wasted no time cranking out projects for Mello’s evolving roster, including The Reset, Gas Mask, and Brown Study in 2010. The projects usually featured a variety of underground artists including Detroit’s own Marv Won, Finale, Invincible, Boog Brown, and Miz Korona. With Brown you won’t get layered keyboards, synthesizers, unnecessary filtered samples, or orchestra aesthetics. Brown’s clean but gritty, sharp but jagged. He gives you honest variations of kick and snare drums and the melody usually resides in the strings, keys, or horns.

“I don’t use the term ‘backpacker,’” he says. “I don’t look at the music that I make or the artists that I make it for as backpackers. I use the term boom bap, because it’s hard to describe this music to somebody without saying boom bap. I don’t do a lot of commercial-style triple-time hi-hats. I’ve produced all over the place, but I usually stay within a certain realm and it’s usually a boom bap style.”

In 2011 he took an auditory pivot releasing Clouds, a laid-back melodic instrumental album built more to fill in the backgrounds at cafes or cold nights snuggled with a good book.

Brown calls it the most important album of his career.

“I come from a battle culture, but I still wanted people to know I can make life music,” Brown says. “I wanted people to be able to relax to my music. It became my highest-selling album. I think yearly, it’s still my highest-selling album.”

By 2012 he started to be recognized more nationally with the release of Trophies with New York’s O.C. and Dice Game with fellow Detroiter Guilty Simpson. “Those really put me on the map,” he says. Then came The Brown Tape with Wu-Tang Clan’s Ghostface Killah, the critically acclaimed Ugly Heroes with Verbal Kent and Red Pill, The Easy Truth with Skyzoo, Anchovies with Planet Asia, and Mona Lisa with Joell Ortiz.

Along the way Brown has also quietly produced tracks for artists that the average hip-hop fan is unaware of, like Danny Brown’s “Contra,” Chance The Rapper’s “The Writer,” and WestSide Gunn’s “Mt. T.”

“For a while West was closing his shows out with ‘Mr. T.’ That was an accident,” Brown says. “Me and West was going to make an album and that was just one song. But that was around the time where he was getting signed, that whole Shady deal, so all that stuff fell through.”

When asked what his favorite album is, Brown looks at the wall above his couch at all 30 album covers and refuses to pick one. “I don’t have a favorite because they were all a specific mood, a specific place,” he says. “Each one of my albums I treat like one of my kids. I don’t rank them, but I love them all equally but differently.”

He acknowledges the quality of his work means the most to his fans, not necessarily the quantity.

“If I make a post today asking, ‘What's your favorite Apollo Brown album?’, everybody will say something different,” he says. “Everyone doesn’t just gravitate to one album. That’s when you know you’re doing it right.”

In the fall of 2019 he released his most ambitious effort, Sincerely Detroit. The 21-track album featured 59 Detroit artists including Kuniva from D12, Slum Village, Nolan The Ninja, Boldly James, Ro Spit, Trick Trick, Royce Da 5’9”, and Phat Kat (just to name a few). The album was more than just a musical love letter to the D. It was a statement piece, a celebratory hip-hop acknowledgement that Detroit’s boom bap culture was alive and thriving and is still part of the fabric of the Detroit sound. Detroit hip-hop has always been a melting pot of boom-bap and street. You can pop in the Old Miami and hear an emcee chopping up nouns and verbs over a ’70s soul sample and some tough drums. Or you can hit Harpos and hear a club banger and grimy street tales over arpeggiated and monophonic bass lines. They all encompass the Detroit experience and diversity. Much like the city itself, Detroit’s hip-hop scene has always been defined but the sum of its parts rather than a singular sound.

During the late ’90s through early 2000s, boom-bap received more national recognition, whereas Detroit’s trap and street artists have dominated over the last 5 years.

“For me there’s not a single Detroit sound,” Brown says. “I think as a producer we have our interpretation of what a Detroit sound is. When I did Sincerely Detroit, that was my interpretation of Detroit’s sound. I don’t think I have a Detroit sound, never have. Dilla to me is the sound of Detroit. That’s who I look at. But I’ve always thought I had an east coast sound.”

Instead of being overly focused on what he felt Detroit wanted to hear, Brown’s production has always been more of a combination of what he wants to make and wants to give to the world.

“I think you start losing when you’re trying to make music for the city that you’re in,” he says. “I think you’re better off in your career if you make music for the world and it just happens to find its way back to the city. You can’t just make music for your block. You gotta have a broader scope than that.”

The result has been an international fanbase that stretches through Germany, France, Italy, and New Zealand, where Brown tours and regularly sells out shows. “They genuinely love the music out there, they respect the music,” he says. “When you do shows here, the crowd is other emcees and producers. Overseas, everyone is a fan. You get spoiled out there. If you go into any club right now and ask who Apollo Brown is, 99 out of 100 people wouldn’t. If you go into any underground club, the numbers will be higher. And if you leave the city the chances of people knowing who Apollo Brown gets even higher.”

“I think as a producer we have our interpretation of what a Detroit sound is. ... I don’t think I have a Detroit sound, never have. Dilla to me is the sound of Detroit. That’s who I look at.”

tweet this

On his newest album Cost of Living, Brown partners with Windy City emcee Philmore Greene to deliver more of Brown’s specific brand of production over Greene’s personal and introspective lyrics. Brown doesn’t give you anything he hasn’t given you before — he just keeps giving you better versions of it. The song “Paradise” is reminiscent of Wu-Tang’s “Can it Be All So Simple,” and in the lead single “Time Goes,” Brown’s steady head-nodding bassline is the perfect medium for Greene’s introspective baritone flow: “Back when entertainment was shared at the same time/ We all moved to the same tune, same rhymes/Same drop of a dime, we shared memories was precious/ Nowadays it seems kind of hectic.”

As Brown has entered his 40s, he’s reflective and more thankful for the journey more now than he’s ever been. Hip-hop is like professional sports: you usually only get a handful of years to earn as much money and notoriety before it all fades away. Brown has defied that. His rise has been slow but sho’. He’s a building block for Mello Music, and his career has ascended because of it.

“I was a nobody at that time so that was big for him (Tolle) to believe in me, to hit me up, and tell me I had what it takes,” Brown says. “I’m in a family atmosphere. I’ve been with Mello for 13 years. We’ve created a brand together. I call myself Kobe on the Lakers.”

While admitting he’s slowing down a bit, Brown has no doubt he’ll reach the 50-album milestone.

“We don’t have retirement benefits. We don’t have 401k matches,” he says. “It’s up to us to take our IRAs to make sure our future is good. We kind of gotta work as long as we can. I have a renewed love for it. There was a time when I thought about going back to school and doing something else. But I’m always going to be in the music industry. Being a producer is what I’m good at. It’s the only thing that can put a smile on my face when it comes to work.”

Brown often feels like he was born in the wrong decade — that his legacy would be evaluated differently if he were around in the ’90s producing boom bap bangers alongside Pet Rock and DJ Premiere. But at the same time, would Erik Stephens be Apollo Brown without the inspiration from those same producers he saw as heroes as teen? Ultimately, Brown’s timing has been perfect for Detroit, and perfect for the world.

“I’d say his style represents how one pays homage while simultaneously carving out his own niche,” says emcee and friend Boog Brown. “The contribution to Detroit hip-hop is that everywhere he goes, he city goes too. It’s the international reach that changes the game.”

“I want to know that I was significant to hip-hop, not just Detroit hip-hop,” Brown says. “There’s that question out there, ‘Would you rather be successful or significant?’ That’s a hard question to answer, but everyone has their own definition of success. But to me, ‘significant’ is more of a concrete word to describe where I want to be. I’m already successful. I got a beautiful wife, beautiful kids, I have a beautiful home, the vehicles that I want, the career that I want. I’m surrounded by great people. But I want to know that I’ve made a significant impact on hip-hop.”

Apollo Brown and Phillmore Greene’s Cost of Living is available on all streaming platforms on Nov. 15.

Coming soon: Metro Times Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting Detroit stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter