In a letter sent to the board, the employees, which included curators, youth and education staff, cafe and bar workers, event assistants, and interns, alleged a toxic workplace under Borowy-Reeder, including “racist micro-aggressions, mis-gendering, violent verbal outbursts, misrepresentation of community partnerships, and the tokenization of marginalized artists, teen council members, and staff.” They cited the departure of three Black curators after just months on the job as further evidence of the hostile work environment, and Ford Foundation Curatorial Fellow Tizziana Maria Baldenebro also announced her resignation, cutting her fellowship short.

By the next week, the number of staffers who signed onto the list of grievances increased to more than 70. That Tuesday, the museum’s board announced in an email to staff and shared with Metro Times that Borowy-Reeder had been placed on administrative leave while an outside firm oversaw what they promised would be a “swift” investigation.

Then, on Monday — just as this story was going to press — a group of current and former employees at the prestigious Detroit Institute of Arts who called themselves the “DIA Staff Action Group” announced a similar coup d'état, promising to release a full list of demands in the coming days. The first was for director Salvador Salort-Pons to be “removed from his role” by Aug. 31, citing recent allegations of racial insensitivity and nepotism in a matter involving the loaning of two paintings from Salort-Pons’s father-in-law to the museum.

“The Board of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) is taking the concerns raised by the community seriously,” the museum wrote in a statement. “We are committed to taking every measure possible to ensure our employees, artists, and the broader community enjoy a creative working environment that is respectful and inclusive. … We have a zero tolerance for harassment, discrimination, or abuse in any form.”

Over at the DIA, the museum defended the loans as being by the books, but said it will hire an independent law firm to review its practices.

“Our Board is aware of the complaints and allegations made public by former employees in recent days and we take them seriously, addressing each of them,” board chair Eugene Gargaro, Jr. wrote. “Importantly, we have full confidence in Salvador Salort-Pons and the leadership team of the DIA, and the high professional standards used to implement the museum’s policies approved by this board.”

In a statement to Metro Times, Borowy-Reeder says, “I am committed to inclusion and racial justice and healing, not just in the workplace, but in society as a whole. Out of respect for all parties, I will withhold any comments until completion of the investigation.”

Seven former staffers, however, tell Metro Times that they decided to leave the museum for one reason and one reason only: because of repeated clashes with Borowy-Reeder.

The museum has a full-time staff of fewer than 20, so the employees who signed the letter span the entirety of Borowy-Reeder’s directorship, which started in 2013. “The museum has the turnover rate of a McDonald’s, like straight up,” Katie McGowan, MOCAD’s former curator of education and public engagement, tells Metro Times.

The employees say things came to head when the coronavirus crisis hit in March, and Borowy-Reeder laid off staff but asked them to continue to work. They say they were also inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, which has seen the removal of CEOs and other leaders across the country as workers come forward with allegations of racism. And they say they were even inspired by an upcoming exhibition at MOCAD from New Red Order, a group of Indigenous artists who call for the dismantling of colonialism, which was to be the museum’s biggest show of the year so far.

But McGowan, who was hired in 2011 and resigned in 2014, says issues with Borowy-Reeder stem from the beginning of her directorship. And when McGowan resigned, she says she alerted the board that it was because of Borowy-Reeder, which she says was ignored.

“Elysia is an extremely erratic and manipulative gaslighter,” McGowan says. “She has no skills in handling people, and basically had unchecked power at the museum because she’s a good fundraiser.”

Too white, too wealthy

As executive director, Borowy-Reeder helped bring a number of buzzy, high-profile exhibitions to MOCAD in recent years, including a solo show by contemporary art superstar Kaws, an edgy look at the erotic art of gay icon Tom of Finland, and Robolights Detroit, an outdoor, psychedelic Christmas-themed found-object installation by Palm Springs-based artist Kenny Irwin Jr., among many others. She joined MOCAD after parting ways as the founding director of the Contemporary Art Museum Raleigh in North Carolina, a position she held from 2011 to 2013. At the time, CAM Raleigh said the museum’s advisory board and the museum foundation’s board of directors decided to “move into new areas of development requiring new leadership,” according to a notice issued by the museum reported by The Triangle Business Journal. (A representative of CAM Raleigh tells Metro Times that as a policy, the museum does not comment on personnel matters.) Weeks later, it was announced that Borowy-Reeder was heading to Detroit.It was a return home; she and her husband, the artist Scott Reeder, both grew up in Michigan. In 2017, Borowy-Reeder took in a salary of $117,830 from the museum, according to the latest information available from GuideStar, an information service on U.S. nonprofit companies.

McGowan admits she had concerns about MOCAD even before Borowy-Reeder joined — she says even in the museum’s early days she was concerned its leadership and audience was too insular, too white, and too wealthy — too “capital-A art,” she says. The museum opened in 2006 in a former auto dealership in Midtown, originally intended to be an offsite contemporary art gallery and performance space for the Detroit Institute of Arts that would exhibit art but not collect it. That plan was scrapped when the DIA chose instead to focus on a massive expansion of its main building, but bigwigs connected to the DIA, led by former Detroit Free Press journalist Marsha Miro, had given MOCAD their blessing. Miro served as its first director, followed by Luis Croquer, who left after three years. Former Metro Times arts and culture editor Rebecca Mazzei served as deputy director for more than a year until the museum hired Borowy-Reeder.

Still, McGowan says she saw its potential, and she was excited to join. “It was chaotic, it was mismanaged, to a degree, but there was none of that toxicity,” she says. “There was solidarity amongst the staff, like a scrappy Detroit ‘we can get it done, we can do this’ kind of thing.”

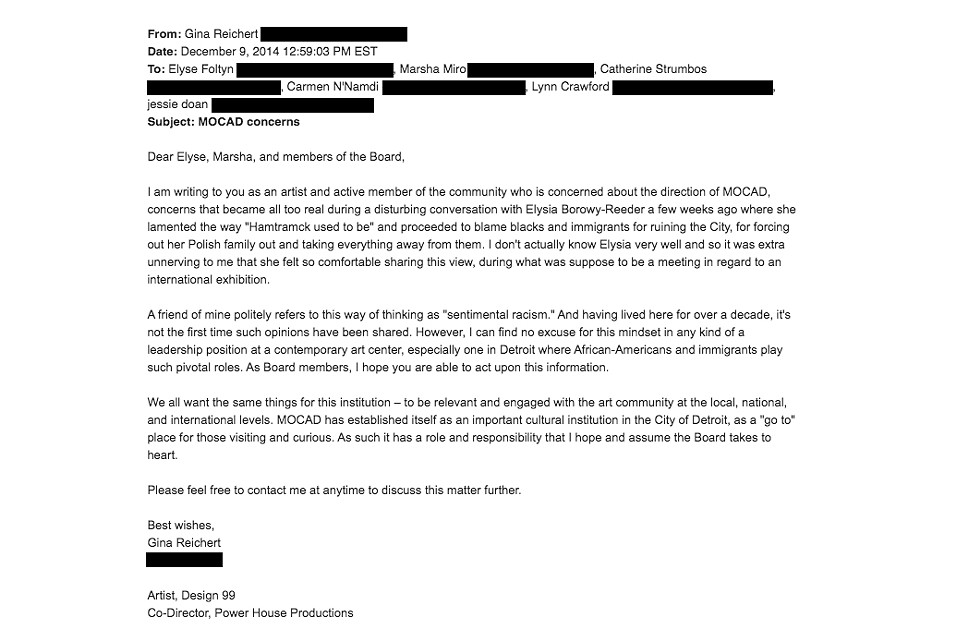

But McGowan says the feelings of racism and classism intensified under Borowy-Reeder. Something McGowan calls “a leitmotif” was Borowy-Reeder’s fondness of saying that her family used to live in Hamtramck but moved when she was young. “She would talk about how Hamtramck used to be such a nice, safe community, and how it got ruined by all of these immigrants,” McGowan alleges. “I was like, ‘Hamtramck was founded by immigrants, it was densely Polish for many years … Do you mean because they’re brown?’ And she just kind of smirked at that.” In a 2014 email shared with Metro Times, artist Gina Reichert, whose partner Mitch Cope served as MOCAD’s first curator, brought the same issue up to the board, writing, “I can find no excuse for this mindset in any kind of a leadership position at a contemporary art center, especially one in Detroit where African-Americans and immigrants play such pivotal roles.”

McGowan says a similar incident played out surrounding an exhibition she had organized at the Mike Kelley Mobile Homestead, a full-scale replica of the house that the eponymous late renowned artist and musician grew up in, which he intended to serve as “a community gallery and gathering space featuring exhibitions and programs created by and for a diverse public which reflect the cultural tastes and interests of the local community,” according to MOCAD’s own website. In that spirit, McGowan, who is part Native American, arranged an art exhibition featuring work by local Indigenous youths to be hosted there — to the objections of Borowy-Reeder, she says.

“I pushed hard, saying this is what Mike Kelley wanted us to have, community exhibitions and stuff that wouldn’t necessarily be recognized in a typical museum setting,” McGowan says. When carloads of Indigenous people started showing up for the exhibition opening, McGowan says Borowy-Reeder started acting strange. “She asked if she could come out and check it out, which is like a weird thing for an executive director to say,” McGowan alleges. “I said, yeah, of course. And she was like, ‘Are they going to, like, hurt me?’ I said, ‘That's ridiculous, Elysia,’ and I just walked away.”

Another incident that McGowan says was illustrative of the tension between the museum’s stated mission to serve the community and the financial forces behind running it came early under Borowy-Reeder’s directorship in 2013, when she rented the museum out to Google for the company to do a demonstration of its new Google Glass product. At the same time, the museum was hosting a lecture tied to an exhibition of the artist Shani Peters, whose work deals with social justice themes.“It was chaotic, it was mismanaged, to a degree, but there was none of that toxicity. There was solidarity amongst the staff, like a scrappy Detroit ‘We can get it done, we can do this’ kind of thing.”

tweet this

Again, McGowan says Borowy-Reeder was dismissive of that exhibition. “She went on and on about how she wished that I would have more of a sense of humor and people are not interested in all the serious ‘Black power’ political stuff,” McGowan alleges. “I said, ‘This is Detroit, people do care about that stuff.’”

On the day of the Google Glass demonstration, an elder artist from Detroit came to MOCAD to listen to the lecture. But unbeknownst to McGowan, Google had rented out the museum’s entire parking lot, too. When McGowan asked if the elder artist could use a parking spot, she says Borowy-Reeder blew off her request.

“She was like, ‘They’re not paying the bills. They can go find another place to park,’” McGowan recalls.

Three Black curators depart within eight months

In recent years, MOCAD made moves to diversify its staff, announcing the hiring of a string of Black curators from the art world outside of Detroit. Jova Lynne came on in 2017 as a Ford Curatorial Fellow, the first Black woman to serve in that role, and she soon organized a sprawling retrospective of the work of the Detroit artist Tyree Guyton. The next year, the museum brought on Larry Ossei-Mensah to serve as the museum’s Susanne Feld Hilberry Senior Curator, replacing Jens Hoffmann, who resigned following allegations of sexual harassment that stemmed from his work at New York’s Jewish Museum. The new hire “[reflected] the Museum’s continued focus on diversity and the next generation of leaders,” according to a press release at the time.But within a year, Ossei-Mensah quietly left the position. (Metro Times could not reach him for comment.) Lynne took his place, an opportunity she calls her “dream job.” In early 2020, the museum brought on another Black curator, Maceo Keeling, as a new Ford Curatorial Fellow.

Just a few months into 2020, both Lynne and Keeling would part ways with the museum as well. When the coronavirus crisis hit, both were initially told they were being laid off, but say Borowy-Reeder asked them to continue to work as the museum tried to secure a federal coronavirus relief loan, assuring them that the state’s unemployment agency would make them whole. They both say they found that concerning, and possibly illegal.

Keeling already had concerns, after just weeks on the job, he was told that he had no budget, and would be taking an assignment instead of being able to curate an exhibition of his own. “It was just not what I signed up for,” he says. “I just moved across the country for a specific thing, and almost immediately was told that wasn’t going to be the case.”

That’s when Keeling says he began to feel tokenized, and decided to take the layoff. “When I say ‘tokenized,’ I don’t mean to invoke an arbitrary or ambiguous definition,” he says. “I mean that I was literally made to represent diversity and opportunities without the actual opportunity. They’re raising funds around giving young diverse curators an opportunity, and then not availing that opportunity.” Keeling says he even felt he had to advise another curator of color to not take a fellowship at MOCAD.

In the meantime, Lynne used the downtime to help take care of her family in New York. Soon, Borowy-Reeder called and said the loan was approved and Lynne could be hired back — but she had to return to Detroit by that Friday.

Lynne says she was perplexed; at that time coronavirus cases in Michigan were surging, and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer ordered the closure of all nonessential businesses.

Lynne was beginning to have her own concerns with the museum, noticing instances where Black artists and artists of color appeared to be paid less than white artists. “I would ask questions about certain funding and certain grants, and the numbers didn’t add up to me,” Lynne alleges. “And then it became apparent we were lowballing certain folks.”

Still, Lynne recalls she had “a great conversation” with Borowy-Reeder, who asked her to commit to five years. But then, as the phone call was ending, Lynne says Borowy-Reeder took a strange turn. “She said, ‘I would hate for our relationship to sour, now is a really good time to resign,’” Lynne recalls. “I don’t know how else to interpret that other than a threat.”

Two other Black employees also say they didn’t feel welcome at MOCAD under Borowy-Reeder: Monty Luke, a DJ, and Paula Smiley, better known to many as the rapper Miz Korona, who appeared alongside Eminem in 8 Mile.

It wasn’t always that way. Luke started working with the museum by curating a Sunday brunch-and-DJs event, Sundays at Cafe 78, and in 2016, he started working for the museum as a public programs curator. But in the summer of 2017, he says he announced to Borowy-Reeder that he would be ending his contract in 2018 to pursue a music career in Berlin.

“She was not happy with this decision and on several occasions derided me for deciding to leave, saying such things as, ‘You must be having a midlife crisis,’ and ‘You’ll never make it there, I don’t know why you’re doing this,’” Luke says via email. After what he calls “months of resulting tension” between the two of them and “an increasing amount of dysfunction amongst the staff,” Luke quit, ending his contract three months early.

Smiley says she first became acquainted with the museum in 2010, when she held a record-release show there.“It just seems like it’s about the dollar, who’s bringing in the money, and who’s bringing in the clout, as opposed to what the purpose and the mission was for the museum.”

tweet this

“I instantly fell in love with the space, and the energy, and the vibe. I always had in mind that I would have loved to work there,” she says. “It was really like a breath of fresh air, seeing a new space that was welcoming to hip-hop artists and community activism.”

Years later, when she saw an opening for a visitor service associate position, she applied. Smiley was elated when she got the job.

“This is what I’ve always wanted to do, to be able to be in a space like this and to be myself, Paula, and also be accepted as Miz Korona, the artist,” she says. “I didn’t want to be going into a workplace where I have to cut off half of who I am in order to be accepted.”

But soon, Smiley began to feel that MOCAD wasn’t the bastion of hip-hop she initially thought it would be. She recalls an incident where Borowy-Reeder discouraged the museum’s bar staff from playing rap music in the café. Another time, she alleges she heard Borowy-Reeder had told the museum’s youth group, the Teen Council, “how to speak proper” so they can learn how to sell their art.

“I wanted to say, ‘What the fuck does that mean?’” she says. “That was off-putting to me because these are Black and brown kids that were there.”

For Smiley, the last straw came at one of MOCAD’s high-priced black-tie gala exhibitions, when she was helping a customer purchase artwork. Suddenly, she was interrupted by Borowy-Reeder, who demanded Smiley drop everything she was doing to help a board member purchase art.

“She spoke to me like I was a servant and not an employee,” Smiley says. “That was what made me realize, OK, I have to set a plan to get out of here.”

Smiley quit in 2019. Looking back, she says she doesn’t think her treatment under Borowy-Reeder necessarily had to do with the color of her skin. “I think it has more to do with my tax bracket,” she says. “It just seems like it’s about the dollar, who’s bringing in the money, and who’s bringing in the clout, as opposed to what the purpose and the mission was for the museum.”

Trouble on the Teen Council

One of Borowy-Reeder’s biggest claims to fame at MOCAD was the establishment of the Teen Council youth group; she launched a similar program during her stint at CAM Raleigh. Many employees interviewed by Metro Times believe it was one of her top selling points to the board, and concede it was part of a great fundraising model — who would say no to helping kids?But Erin Martinez, who oversaw the museum’s youth program starting in 2018, says that youth appeared to be the least important thing about the program to Borowy-Reeder.

Martinez says on her second day of work, she and Borowy-Reeder had a meeting in the museum’s café, where Martinez — who came to the job with 20 years of experience working with youth — started asking questions, just trying to figure out just how much autonomy the Teen Council had and what her role would be.

“I looked at myself as an adult advocate in a way, or at least that’s how I saw my role,” Martinez says.

But as Martinez asked questions about her new role, she says Borowy-Reeder slammed her hands on the table, and disparaged her for “creating problems.”

“Everyone was taken aback, we were stunned silent,” Martinez recalls. “And I was just looking from face to face, trying to read in their faces, like, is this normal?”

That’s not to say, Martinez says, that Borowy-Reeder didn’t help get some of the Teen Council alumni jobs at the museum, or write them letters of recommendation to help get them into college. But Martinez was perplexed that despite the fact that the museum used photos of the Teen Council on its website, Borowy-Reeder never seemed to remember any of the members’ names.

“That’s sort of the quintessential practice of tokenization, is having these programs, but not really running them with any level of intention, integrity, thoughtfulness, reflectiveness, or even assessment,” Martinez says. “I never saw her heart in it. … For me, if you don’t know their names, how much do you really care?”

She adds, “tokenization is not necessarily absolute heartlessness, it’s just that the wrong person gets centered in tokenization.”

She says tensions escalated in January, when Borowy-Reeder installed the child of a potential new board member on the Teen Council, bypassing the traditional method of allowing the youth to vote. Martinez pushed back, comparing it to the “Varsity Blues” college admission scandal, where wealthy families unfairly got their children into elite schools; in response, Martinez says, Borowy-Reeder said she reserved the right to appoint teens to the council. When Martinez was forced into explaining to the Teen Council what had happened, they asked to address their concerns to Borowy-Reeder directly. Borowy-Reeder refused to meet with them, she says.

“One of the teens was from a very wealthy high school in the suburbs,” Martinez says. “They said, well, that’s how it works at my school, too. You know, like the big donor kids always get special treatment. It was just so heartbreaking because they just said it so frankly. Like, oh my God, yes. And we can also challenge it, you know?”

Martinez says she was subject to “near constant email harassment” from Borowy-Reeder after the incident until she was laid off due to the coronavirus crisis.

Drama at the DIA

Over at the DIA, its troubles culminated in a whistleblower complaint filed with the IRS and the state attorney general reported last week by the New York Times, accusing Salort-Pons, who has served as director since 2015, of a lack of transparency concerning the museum exhibiting two paintings owned by his father-in-law, Alan May: El Greco’s “St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata,” valued at $5 million, and a painting attributed to the circle of Nicolas Poussin, “An Allegory of Autumn,” valued at $500,000. Exhibiting artwork at a museum can increase its market value.Salort-Pons, who earned a salary of $475,000 from the museum before taking a 20% pay cut due to economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic, defended the loans. “It’s a common practice for American museums to engage collectors and patrons asking them to loan paintings,” he told the NYT. “An Allegory of Autumn” was loaned to the DIA in 2010, when Salort-Pons was working as a curator for the museum; then-director Graham Beal defended that loan as well, telling the NYT that it was “totally above board and benefited the DIA as much, if not more, than the lender.” The NYT reported that the DIA’s guidelines say that while the museum can loan artwork from family members, “care should be used to achieve objectivity in such cases,” and lawyers representing the whistleblowers say that Salort-Pons should have shown more transparency in justifying why the work deserved to be shown in the museum’s collection. Salort-Pons is also accused of using the museum’s conservation department to clean and restore paintings owned by May that were not intended to be exhibited at the museum, but he told ArtNet that the department is reimbursed for work done on museum time for private collectors.

Beyond that, the DIA leadership is accused of many of the same complaints as MOCAD’s: institutional racism and a toxic workplace, resulting in high staff turnover, though the museum maintains that its turnover rate is less than the national average for a nonprofit.

The museum has taken measures to address diversity and inclusion. Following the passage of a regional millage in 2012, which supports the museum with a property tax increase, Salort-Pons announced his intention to transform the DIA from a tourist destination into an institution that reflects “the demographics of our visitors to mirror that of the tri-county area.” To that end, in 2017, he hired Lucy Mensah and Taylor Renee Aldridge, both Black women, as assistant curators in the museum’s contemporary art department. Within a year, they both resigned. Mensah told the Detroit Free Press she believed she was a “token hire.”

“Taylor and I were fully aware of what the director hoped to achieve by hiring us,” Mensah told the paper. "He was making a statement that the DIA was moving in the right direction in terms of diversity and inclusion.” Echoing the complaints of the Black employees at MOCAD, Mensah said the DIA “premise some of their hires as a way of diversifying the voices of the institution, but at the same time they don’t actually appreciate those voices.”

“One thing is to diversify your team. Another thing is creating an environment of inclusion where that team that is diversified can be successful,” Salort-Pons told the Free Press. “And I think we were unable to create a sustainable work environment, inclusive work environment, for them that they would be successful in.”

Last month, the museum’s former digital experience designer, Andrea Montiel de Shuman, also announced her resignation. A Mexican immigrant, Montiel de Shuman wrote of her decision to quit in an essay published on Medium, alleging a lack of “cultural competency” at the museum, including what she saw as a failure of the museum to address the concerns of the growing Black Lives Matter protests and the museum’s decision to exhibit “Spirit of the Dead Watching,” a painting by Paul Gauguin of his 13-year-old Tahitian “wife” lying face-down naked on a bed, alongside “The Yellow Christ,” which depicted a crucified Jesus.

“When I saw the cross near Tehamana’s gaze of terror, I was immediately transported to the terror I experienced as a young girl after being molested by a worship leader,” Montiel de Shuman wrote. “On that purple bed I no longer saw Tehamana, it was my naked body, exposed, and my colleagues were collectively watching.” When Montiel de Shuman voiced her concerns to leadership, she said she was told it “was largely a personal issue (meaning, only I had a reaction since I was molested as a child)” and that “the DIA was not going to be a censoring institution.”

While the museum did put a label next to the painting saying “the subject matter calls attention to racial and sexual power imbalances during the era of European colonialism,” and it listened to Montiel de Shuman’s suggestion to warn schoolchildren visiting the museum of the sensitive subject matter, Salort-Pons told the Free Press that “I think Andrea would have liked us to have done more.”

Salort-Pons is also an immigrant — he moved to the U.S. from Spain in 2004, and joined the museum in 2008 — and admits he could learn more about racial dynamics, particularly the Black experience.

“I will never know the struggle of Black Americans because I came from another country,” he conceded to the Free Press. “For me, as a European, I have to learn everything about the Black experience in America. Even being an immigrant here, I was afforded a great deal of privilege, so my goal is to learn as much as possible so I can help the DIA to be responsive to our communities.”

Follow the money

Many of the employees that Metro Times interviewed said they don’t think Borowy-Reeder is racist. But they think her ultimate priorities lay with the board of directors, who are tied to MOCAD’s wealthy donors. Like many art institutions, the DIA also relies on wealthy benefactors; after the city filed for its record-breaking municipal bankruptcy in 2013, the museum was rescued by nearly a billion-dollars bailout from foundations, private donors, and the state. “The bond between museums and wealthy collectors is one of the essential relationships of American museums,” the NYT reported. “Without the generosity of such patrons museums could likely not afford the art that enhances the visitor experience.”But MOCAD Resistance wonders how the board could be so blind to Borowy-Reeder’s actions when concerns were brought up years ago — that, they allege, either means the board hasn't been paying close enough attention to the inner workings of the museum, or they knew but just didn't care.

Plus, the “independent” investigation into Borowy-Reeder is being helmed by the national law firm Locke Lord — but the museum employees are skeptical that the investigation is truly independent because board member Marisa Murillo is a partner at the firm.

Elyse Foltyn, MOCAD’s board chair, says that the firm will conduct a thorough, impartial investigation. “We are fortunate to have a board member who is a partner at Locke Lord, an international law firm with 21 offices and over 600 attorneys, which has an entire practice group dedicated to this type of investigation,” she tells Metro Times via email. “Most importantly, Locke Lord has a long-standing rich commitment to, and is celebrated within the legal community for its efforts in diversity, inclusion, and equity within its own firm. The partner our board member brought us has a sterling reputation for conducting precisely this type of investigation. She has provided her considerable expertise in a most generous fashion.”

Foltyn maintains the board’s position is that it was blindsided by the allegations. Of the 2014 letter to the board sent by Reichert warning of Borowy-Reeder’s behavior, Foltyn says she did not see it until recently. Her email address is among those the original memo was sent to, however, according to an email shared with Metro Times.

“Most of my colleagues and I were unaware of this letter until last week when the subject came up at one of our meetings,” she says. “It appears that some board members received it and chose not to share it for what they believed were legitimate reasons. It is premature to reach final conclusions with respect to this serious and sensitive situation. Nonetheless, as MOCAD Chair, I can assure you that we will implement improved reporting requirements among MOCAD leadership.”

Two days later, Miro replied all in an email shared with Metro Times. “We are taking your email very seriously,” she wrote. “We want to answer you and follow up in the best way we can. So please know we will be back to you with a response and ideas we'd like to discuss with you in a few days. Thank you for brining this up to us.”

Board member Terese Reyes says she has taken a leave of absence in light of the shakeup. She is optimistic that the board will make the best decision for the museum and its employees.

“Prior to my departure, I advised the Board of Directors and hope they will take the proper steps to ensure that their employees’ commitment to this institution is reciprocated by its leadership, working on their behalf with equal vigor to remedy harm done where possible, and to prevent it in the future,” she tells Metro Times in a statement. “Like many of those who have shared their experiences, I continue to believe in the possibility of MOCAD’s mission and vision. That said, that possibility demands substantial reflection and change to become a reality.”

Other former MOCAD employees tell Metro Times they understand the challenges of striking a balance between appeasing both the museum’s community and its donors.

“I think Elysia is a brilliant fundraiser, and I will give her that,” Lynne concedes. “She really is. And I know her job is hard. But at the same time, in this day and age, what is required is to create an equitable, compassionate engagement in the arts. … I don’t know that, given her hot-headedness and narcissism, it would be possible for her to take MOCAD to the place where it needs to be, because at the end of the day, I was always left trying to explain her behavior to artists in the community — and that is inappropriate.”

“She has a really sort of duplicitous side, where like the moment a board member or someone she wants to impress comes around, she really knows how to behave,” McGowan says. “And when people say she’s a good fundraiser, they mean she’s good at donor relations, knowing whose ring to kiss.”

“To me, I look at MOCAD like a beautiful apple on the outside, but when you bite into it, it’s as if the core is rotten,” Smiley says. “And it’s like, how do you fix that?”

Still, Smiley is hopeful. “It has potential,” she says. “I’ve seen it before she got there.”

The series of letters signed by the “MOCAD Resistance” lists several demands for the board, including the resignation of Borowy-Reeder, an employee-elected board member to represent employee interests, and more racial diversity on the board itself, among others. In solidarity with the MOCAD employees, New Red Order pulled its show in the 11th hour, telling the board it will only resume when they agree to meet the employees’ demands. The group also doubled down on calls for the museum to follow through with its promised “land acknowledgement,” a formal statement acknowledging the ancestral inhabitants of their land and concrete actions demonstrating commitment, which was a precondition of the New Red Order exhibition.

The members of MOCAD Resistance tell Metro Times they took the extraordinary measures out of a love for the museum.

“We are concerned about the future of the institution if it does not act now to foster a safe and equitable work environment,” MOCAD Resistance wrote in their letter. “Time and time again the Executive Director has driven away the crucial staff who have brought their talent, expertise, and good will to attempt to bring the institution ‘to the edge of contemporary experience,’ as MOCAD’s mission says. The ‘adventurous minds’ and ‘diverse audiences’ who MOCAD hopes to engage with are not served by the current leadership.”

“I think that we would like to impress that this is coming from a place of deep care and concern for the artistic community in Detroit, and for the museum itself,” says former curator Tizziana Maria Baldenebro. “I think many of us agree that this is an important place that needs to be for the arts and for the artistic communities in Detroit.”

Lynne agrees. “Detroit deserves better,” she says.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.