July 1930. Unemployment rates in Detroit were at a staggering 34 percent. Prohibition was law, if a poorly enforced law. The city reeled under a heat wave worse than any it had experienced in decades. Political tensions simmered, and soon all-out gang warfare erupted on the streets. Later dubbed "Bloody July," the first two weeks saw 11 murders, nine of which were tied to underworld activity. By the end of the month, the city would oust its mayor in the only successful mayoral recall in Detroit history. Further deaths that month would include a Hamtramck police officer, a black teenager in the wrong place at the wrong time, and a beloved radio host whose murder remains unsolved today.

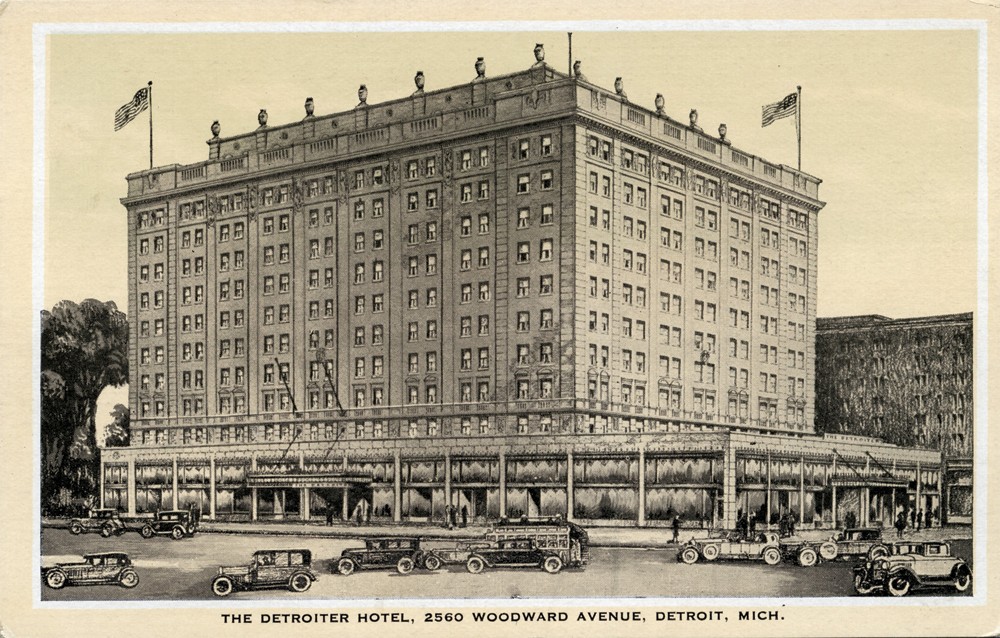

The crime wave began and ended at the same spot, the infamous LaSalle Hotel on Woodward and Adelaide. On July 3, William Cannon and George Collins, small-time Chicago bootleggers trying to muscle in on the Detroit scene, were shot and killed by two men who would later be accused, if not successfully prosecuted, of involvement in the July 23 death of radio host Gerald E. "Jerry" Buckley in the LaSalle lobby. Panicked rush hour commuters fled their cars on Woodward, fearful of more gunfire.

As the month wore on and temperatures climbed, more deaths piled up. On July 5, Barney Roth, a Hamtramck undercover police officer, was murdered in his home alongside John Mietz, a bootlegger he was to escort to court. Two days later, after a power vacuum in the city's Italian Mafia led to vicious feuds, brothers Joe and Sam Gaglio were shot down at a gas station. Within a week, six more died in battles on Jefferson Avenue and all over town as different factions vied for control.

Meanwhile, Detroit Mayor Charles Bowles faced a bitter battle with voters as a recall petition was approved and scheduled for July 22. Petitioners charged that Bowles gave lucrative city contracts to boosters who lined their own pockets, and that Bowles was a corrupt racketeer who prevented law enforcement from stopping the increasing violence. Chief among Bowles' critics was Buckley, whose popular WCHB radio show denounced corruption in the city.

And the heat climbed. By July 12, 72 were dead from the Midwestern heat wave. By the 19th, the city was hotter than it had been in 25 years. Four people died in Detroit that day due to the heat. As the day of the recall election approached, both sides grew increasingly acrimonious. Bowles' key aides deserted him publicly, citing fraud and corruption on the mayor's part. Political factions took to the airwaves in hysterical rants against their opponents, but it soon became clear that Bowles would likely lose the vote.

On the day of the recall vote, the weather finally broke. As more than 120,000 voters headed to the polls, rain showers brought temperatures to acceptable levels. But other storms were brewing, and before the next morning, two deaths would illustrate the depths of vice to which the city had sunk. One would attract national attention for months to come; the other wasn't even reported in the papers.

Arthur Mixon was an African-American teenager who worked the city as an ice vendor. On July 22, he was tossing a ball with some friends near a barn at Hastings and Henry Street, epicenter of the Purple Gang's operations. When his ball rolled under the wall of the garage, Mixon looked through the window to see if he could find it. This caught the attention of two of the Purple Gang's "cutters" — men who diluted Canadian whisky with water and solvents and rebottled it, turning one gallon into 10 or more. Morris Raider and Phillip Keywell chased Mixon into the street and gunned him down as his friends watched in horror. Although the gunmen were quickly caught, the first trial ended in a jury deadlock, with jurors receiving death threats and bribes. The two eventually went to prison for the murder, with Keywell serving a life sentence and Raider receiving 12 to 25 years.

Mixon's death went unnoticed and unreported in the chaos surrounding the recall vote and its aftermath. By the end of the day on Tuesday, July 22, Detroit voters called by a margin of 30,956 to oust the mayor. Buckley spent all day tallying votes and reporting on the election. Shortly after midnight, he'd filed his final story when he received a phone call at the WCHB offices in the LaSalle hotel from an unidentified woman. He left shortly thereafter for the hotel lobby, where he picked up a newspaper and sat down in a chair, seemingly waiting for someone. At 1:45 a.m., three gunmen came in the front door from Woodward and opened fire, shooting Buckley with 11 bullets. They calmly walked past horrified onlookers and boarded a car driven by a woman immediately after.

Detroit was in an uproar. Rumors flew, and soon Buckley's golden reputation came under attack. Police Commissioner Thomas Wilcox, appointed by Bowles after Bowles fired his predecessor, trumped up allegations of racketeering and extortion against Buckley, but these were later proven fraudulent. Wilcox proved incompetent in handling the search for Buckley's killers, arresting and releasing dozens of suspects. Three eastside Italian gangsters were tried, but between Wilcox's tainted reputation — and witnesses and jurors so afraid of mob retaliation that they preferred prison for contempt of court to testifying — the trial ultimately ended in acquittal.

By the end of the month, temperatures had crept back up, and Detroit police and Prohibition agents were turning up the heat on its criminal element. A July 27 raid on the Grosse Pointe Village home of Joseph "Singing in the Night" Catalanotte started with a two-hour siege and ended with the arrest of four gangsters. Two of the men apprehended were accused of the July 5 murders of Roth and Mietz. Again, though, witnesses proved hostile and the case was thrown out.

On July 28, the temperature was at 100 degrees and there was no reprieve in sight for the heat wave or the crime wave. It would take years for repeal to slow the tide of Mafia activity in Detroit. Bowles lost his rerun election to Frank Murphy, who would later go on to serve in the U.S. Supreme Court and be the first to use the word "racism" in a Supreme Court decision. Unfortunately, Arthur Mixon wouldn't be around to hear it.