In early June, just before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled same-sex couples could marry nationwide, Michigan's representatives were already busy crafting and passing a fresh assault on LGBT and others' civil rights.

Under the new law, Christian and Catholic adoption agencies that receive taxpayer money could now tell same-sex couples, unmarried couples, Muslims, or anyone else seeking to adopt a child who isn't a Christian to get lost.

As multiple polls show, the self-righteously entitled "Religious Freedom Restoration Act" was met with a clear thumbs down from most residents: Around two-thirds disapproved. Conversely, polls found a large majority of Michiganders supported the Supreme Court's ruling and gay marriage in general, and some polling indicated 70 percent wanted same-sex couples' civil rights expanded.

Yet, against much of the state's wishes, the Republican-led legislature pressed ahead with the new law, "restoring" religious freedom that had never been in danger and restricting the freedoms of thousands and thousands of residents.

This isn't the first time that lawmakers have acted against public opinion. In 2012, a poll found more than 70 percent opposed a proposed law that would allow concealed firearms in the state's schools. The Republican legislature shrugged at the vast opposition and sent the bill to Gov. Rick Snyder's desk anyway, but even the governor — no one's idea of a liberal champion — vetoed it, partly on the grounds that a majority of the state opposed the idea. Now a new version of the law is making its way through the Senate over similar public opposition.

With increased frequency over the past five years, new state laws have gone hard against the grain of public opinion. The normal response would be for voters to bounce lawmakers in the next election. But that can't happen in Michigan. And that's because the state's legislative districts are gerrymandered to within an inch of their lives to give Republicans unchecked power.

Let's put this in perspective: In 2014, Michigan voters cast 30,000 more ballots for Democrats than Republicans in the state's House of Representatives races. Despite that, Republicans hold a huge advantage of 63-47 there. As for the state Senate races, the raw count came in close to even but Republicans hold a 27-11 majority.

The same problem is found in U.S. Congressional districts. Democratic candidates received 50,000 more votes in 2014, but Republicans sent nine representatives to Washington, D.C. while Dems sent five.

And that leads to unpopular laws and dysfunctional politicians, which are the end result of gerrymandering. So what is it exactly? It's the art of politicians in power — in Michigan, this means Republicans — redrawing legislative district lines in such a way that Democratic voters are herded into a small number of districts while a majority of Republican voters are spread among a much larger number of districts. That means when the votes are tallied, the Democrats, pushed into tiny pockets, get as many or more votes, but the Republicans win far more districts and send more reps to Lansing and the nation's capital. That also creates safe districts that insulate Republicans from voter anger, allowing them to pass unpopular laws with no repercussions to their future re-elections.

To put it in even clearer terms: Gerrymandering is a form of legal election theft that predetermines results and creates a one-party system.

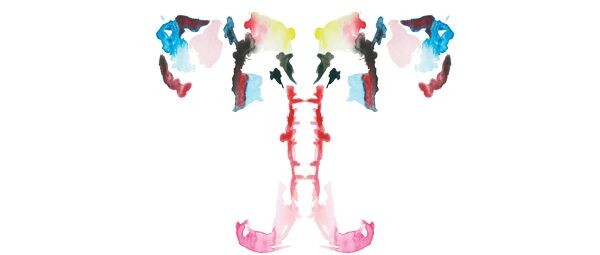

As many in Michigan and other states argue, there's an inherent conflict of interest for politicians to draw their own legislative districts, which, when looked at on a map, can resemble a Rorschach test more than any reasonable political "district" guided by geography and demographics.

"I don't think politicians should be picking their voters. Voters should be picking their politicians," says Rep. Robert Wittenberg, an Oakland County Democrat working to call attention to the issue. "More people voted for state House Democrat candidates, but Republicans have a 63-47 majority. With those overall numbers, there shouldn't be that big of a majority. If there is, then the lines are drawn unfairly."

The "gay adoption" legislation and "tots and glocks" redux are only a few in a litany of Mississippi-esque laws that are far to the right of what polls show Michigan's mainstream finds reasonable or responsible.

Most Michiganders don't like "rape insurance" for instance, or financial martial law presided over by an emergency financial manager, or allowing anyone to discriminate against gays and religions of any sort. Polls also found a large majority support campaign finance reform, want more funding for public schools, and, in 2014, supported immediately bumping the minimum wage to $10.10. Under intense public pressure, lawmakers eventually increased the minimum wage, but it will only get to $9.20 in 2017.

Moreover, Republicans get creative in overriding voters' will, if need be. In 2012, Michigan residents repealed the unpopular emergency manager legislation. The law allowed the state to strip locally elected governments of their power, and residents were uncomfortable with that. Republicans didn't care, drafted a new version of the law, and rammed it through a month later.

Beyond the unpopular laws, gerrymandering legislative districts can turn them into cultures for batshit crazy politicians.

Take, for example, world-class fools like Todd Courser and Cindy Gamrat. The tea party duo continues to make national headlines with fallout from their fake gay sex and drug scandal. Former tea party Rep. Dave Agema passed them the baton. He's infamous for spending a recent Easter and New Year's Eve posting Ku Klux Klan propaganda and other hate speech on his Facebook page.

The state's new laws, its government's treatment of some residents, and politicians' behavior, are enough to generate embarrassment and shame. It creates sort of an identity crisis — "This isn't us!" — as some have noted.

Still, for the most part, not many see the link between the state's gerrymandered districts and their frustration, and it hasn't exactly been a shout-at-the-computer item. (A generally smart friend asked if "Gerry" was a man or woman when the issue came up.) While redistricting is a part of the mechanics of politics, those self-appointed to tackle it say its importance can't be overstated.

"It has a direct impact on everyone in the state, every day, in terms of what the legislature does," says Mark Brewer, an elections attorney and the former head of the Michigan Democratic Party. "In the end, this is about the voters. This is about politicians setting districts that predetermine the results. That's what the people are upset about."

Interest in a fix is growing, however. This year has seen the first serious discussions on establishing an independent redistricting commission to straighten out the legislative lines to accurately reflect Michigan's electorate.

That measure has worked well in other states, according to those who aren't losing power. In California, incumbents were so safe that only one congressional seat changed party control in 255 elections over a 10-year span. The state saw unprecedented turnover after the lines were redrawn in 2011.

Naturally, many Michigan Republicans will bray that redistricting reform is an attempt by Democrats to grab power. But their counterparts in states like Illinois and Maryland, where Democrats have pretzeled the districts in such a way that Republicans are the guaranteed minority, see it different.

Those two states, along with West Virginia, are among the nation's most gerrymandered and are controlled by Dems, according to a Washington Post analysis. It also found North Carolina, Louisiana, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Alabama among the most gerrymandered, and they're controlled by Republicans.

"This is what politicians do," says Sue Smith, vice president for redistricting for the nonpartisan League of Women Voters. The league is spearheading an effort to illuminate the connection between voters' dissatisfaction and gerrymandered districts.

"Gerrymandering is something done by Republicans in Michigan and Democrats in Illinois. This is an issue that's bubbling up across the country in different states," Smith says. "When you let legislators draw lines in a way that keeps them in power, many times the action they take doesn't reflect desires of the voters. It's just what happens, but it's not fair to citizens."