Part One of two.

Click here for Part Two of Curt Guyette's series on Detroit Public Schools.

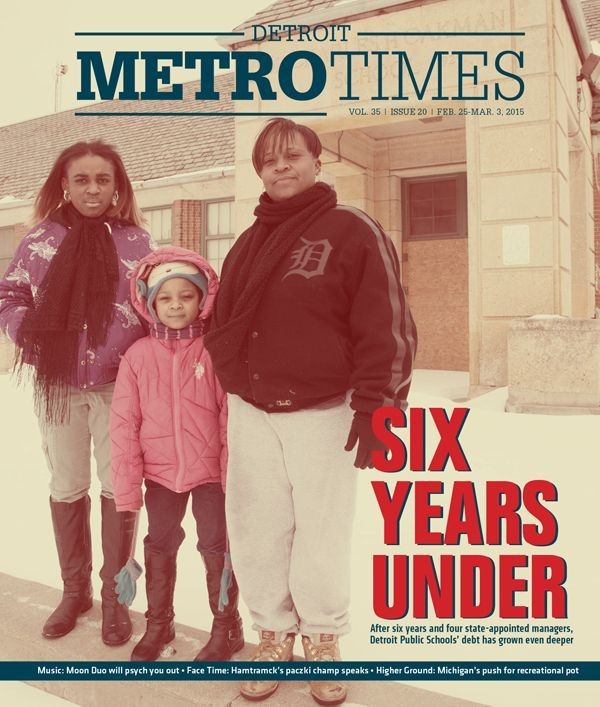

On a recent night when temperatures hovered near zero, Aliya Moore and her two school-aged daughters bundled up for the 20-minute drive from their home in northwest Detroit to the Frederick Douglass Academy, a public school not far from Midtown.

They made the trek through the bitter cold to join about 40 others for a meeting of public officials who've been stripped of all their power — the Detroit Board of Education. The board discussed legal action to challenge the appointment of yet another state-appointed manager to run the district — the fourth in less than six years — and floated the idea of seeking an independent audit. To pursue either of those things, the board would have to figure out how to do so with no district funding — which has also been eviscerated by order of the emergency manager.

Until a few years ago, Moore never bothered coming to meetings like this. For a long time, she confesses, little thought was paid to either the board or the emergency manager.

It's not that she didn't care about the quality of education her children receive. She cares deeply. But as long as things were going well at her neighborhood school, she didn't feel the need to become enmeshed in the conflicts surrounding the district's long-standing financial crisis.

And things were very good at the Oakman Elementary-Orthopedic School, specially built in the 1920s to accommodate the needs of children with physical handicaps.

Moore's eldest daughter, 13-year-old Chrishawna, had been going there since kindergarten. Tyliya, now 7, spent much time at Oakman as well, accompanying her mom on frequent visits to do volunteer work there.

Neither child has a disability. Instead, Moore liked that the school was within walking distance of their home. More than that, though, she wanted Chrishawna and Tyliya to learn about diversity and how to get along with a variety of other children.

In that respect, Oakman offered a special opportunity.

The girls say they loved it there, and formed close relationships with the other kids and the staff, most of whom had been at the school for years.

When it was announced that the place would close in 2013 in an attempt to help narrow the district's perpetual budget gap, the community rallied in an attempt to save it. Activists and parents joined students, drawing widespread media coverage.

But the protests, heart-rending as they were, failed.

That's in line with the purpose of Michigan's emergency manager law, considered by experts to be more far-reaching than any other like it in the nation. Given vast authority over financially struggling cities and school districts, appointed emergency managers can make unpopular cuts without having to worry about being voted out of office by irate constituents.

So Oakman's doors were boarded up and its students sent to other schools less well-equipped to meet their needs.

And Moore was transformed into an activist.

"Unless it is affecting you, you don't get involved," she said. "You think, 'That's not my fight.'"

Because of its unique qualities, she believed the school would survive no matter how bad the district's finances grew. She called it, "being in my Oakman bubble."

"We thought they would never close Oakman," said Moore.

But close it did.

Now, its interior ravaged by scrappers and badly damaged by the elements, Oakman is unlikely to ever reopen.

Moore has a hard time accepting that.

"I hear people say, 'Let it go.' But I can't let it go," she said.

For her and others, Oakman has become a symbol.

"Why would you attack the smallest and most vulnerable?" asked Moore, who is featured in a recent documentary that chronicled the unsuccessful fight to save the school and exposed what advocates say was the district's duplicity in justifying its actions.

Moore considered the closure an assault on her "babies," meaning not just her own girls but roughly 320 children attending Oakman. So she turned to the school board for help.

That's when the full effect of living in a school district under the control of an emergency manager began to sink in.

The board can't set policy. Its members have no say in selecting the district's superintendent or where resources are directed. Board members can hear complaints from parents but have no ability to take any meaningful action. And they were powerless in trying to block the closure of Oakman, or any other school.

As some of the members are prone to say, they are a "board in exile."

The state takeover — at least the most recent iteration of intervention — began in March 2009, when Robert Bobb, a former president of the Washington, D.C., Board of Education with much experience as a city administrator, was appointed emergency financial manager of a district then responsible for educating some 95,000 students.

Now, nearly six years later, that number has plummeted by nearly 50 percent, with 48,900 students enrolled in the district, according to the most recent numbers posted online by the district.

The number of schools has fallen dramatically as well, down to 103, with more closures slated. There were 198 DPS schools during the 2007-08 school year, the last full year that an elected board had full responsibility for overseeing the district.

In one of the news stories about Oakman's closure, it was reported that the school would be one of four shuttered by the district after the conclusion of the 2012-13 school year. At the time, EM Roy Roberts — the second of four appointees to run the district — promised there would be no more after that because DPS was finally getting its financial house in order.

Roberts' promise proved to be false.

A revised deficit elimination plan submitted last year by Jack Martin, the emergency manager who succeeded Roberts (and who has recently been replaced by yet another EM), calls for the closure of 24 more schools and other district-owned buildings in the coming years in an attempt to produce a balanced budget and eliminate the accumulated "legacy" deficit.

That tide of red ink — annually amounting to tens of millions of dollars, and sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars — isn't the only legacy DPS is dealing with.

The district's struggles can be traced to a skein of historic factors, beginning with the city's long-declining population, a trend that started in the 1950s and continues today.

Another major factor was the approval of 1994's Proposal A in a statewide referendum that radically changed the way Michigan finances education, shifting from a primary reliance on local property taxes to a "per pupil" foundation grant provided by the state.

The two factors — the continued loss of students and the state funding that comes with them (currently $7,296) — combined with a host of other problems to throw the district into a long downward spiral.

In an attempt to reverse that trend, the state has tried twice in the last two decades to address the crisis — not by addressing the underlying structural issues, but by usurping the elected board's power.

The first big shift came at the end of the last century.

In 1999, then-Gov. John Engler signed into law Public Act 10, which removed the elected school board and replaced it with a seven-person "reform" board, with six members appointed by the mayor (Dennis Archer at the time) and the state superintendent of public instruction serving as the seventh member.

The rationale for taking such an extreme step was laid out by the defense in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the takeover law:

"The Reform Board came about as a result of a desire to improve the Detroit Public Schools, a school system many had identified as in distress. In 1997, the old school board initiated a study of the Detroit Public School System. The board asked New Detroit Inc., a nonprofit group whose mission is to improve the social and economic status of Detroiters, to conduct this study and to provide specific recommendations for improvement. New Detroit constituted a Review Panel, and the Panel spent hundreds of hours studying the Detroit Public Schools.

"In July 1997, the Review Panel issued a report. The report found serious problems with the governance, administration, management, finance, and operations of Detroit Public Schools. The report also noted that Detroit Public Schools students score poorly on achievement tests and that Detroit Public Schools suffers from a high dropout rate. The report recommended immediate and fundamental change at every level."

The court upheld the law.

For those fighting the takeover, it was a bitter loss.

"When the 1999 takeover was implemented, DPS had modestly increasing student enrollment," wrote public-school advocate Russ Bellant in a 2011 report by Critical Moment, a local independent magazine. "The District had a $100 million positive fund balance and academic scores in the broad mid-range of districts in the state. There was no performance justification for the takeover."

"The conventional wisdom," contended Bellant, "is that the actual reason for the takeover was to take control of $1.2 billion remaining from the $1.5 billion bond approved by voters in 1994. It was a golden egg that tempted too many in Lansing and Detroit."

In November 2004, as the result of a sunset clause in PA 10, Detroiters were able to decide whether they wanted the "reform" board to remain in place or return power to an elected board. The results were overwhelming. By a margin of 2-1, Detroiters voted to have an elected board.

Voters went back to the polls in November 2005 to select the new board, which was installed two months later. One of the first orders of business was figuring out how to recover from the actions of the reform board, which had taken a $100 million surplus and turned it into a $200 million deficit.

Despite the scope of the problem, the elected board wasn't given much time to fill that substantial hole. In a little more than three years, the state would again intervene.