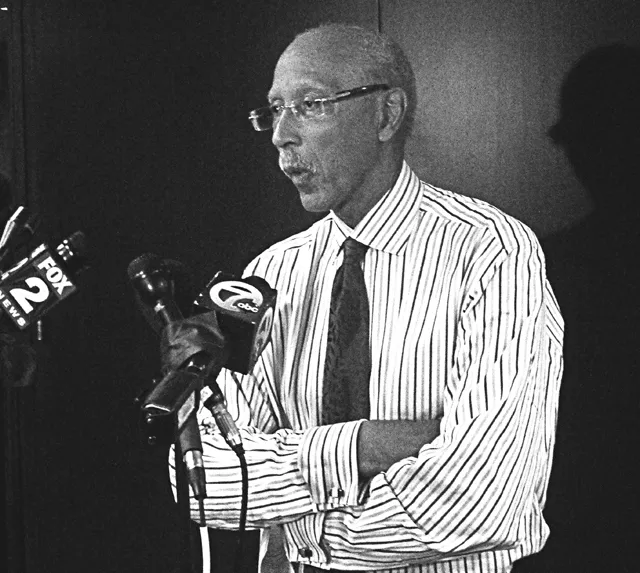

During the press conference Dave Bing held last Friday to announce that he would be laying off 1,000 city workers in an attempt to keep the city from running out of money next year, News Hits had a question for the Detroit mayor, who readily admitted that the cuts will certainly have a significant, negative impact on services to city residents.

Given that assessment from the mayor himself, we wondered, how could the cuts not add another big twist to the long downward spiral that's been going on since the mid-1950s, when the city's population peaked at nearly 2 million and then began its long decline?

We've seen how it has all played out: As the population falls so do income and property tax revenues, requiring cuts in services. As services decline, more people are inspired to leave, resulting in further revenue declines, causing more people to leave. And on and on, until you get to the place we are now.

With the city's population currently hovering somewhere around 700,000, we wanted to know how the drastic cuts being proposed by the mayor (or, for that matter, the even more drastic cuts being proposed by the City Council) won't make the situation even worse in the long run.

In response to our question, the mayor's lips began to move and words came out of his mouth, but nothing in the form of a coherent answer materialized.

To be fair, we can understand why Bing avoided answering the question. Because the bottom line is that, although drastic measures may be needed to keep an emergency manager from being appointed by the governor, the only truthful answer is that the austerity measures being proposed will inevitably drive the city further into the hole.

We had other questions as well, but Bing didn't stick around long enough for us to throw them his way. And so, we went looking elsewhere for answers.

For example, is it a certainty that an emergency manager will be imposed on the city? Most pundits seem to think so. Over at the The Detroit News, editorial page editor Nolan Finley left no doubt he believes that will be the case in a column that appeared Sunday.

"Detroit is out of time," opines Finley, "and Bing's failure to act decisively to turn back the cash flow crisis makes it inevitable that an emergency manager will be appointed by the state to make the hard decisions and common sense reforms that should have been made decades ago."

What strikes us as odd is that Finley, while apparently rooting for an emergency manager to be appointed, shares our analysis of the consequences that will bring:

"There will be fewer amenities, fewer cops on the street, fewer reasons to live in the city," writes the unabashed right-winger. And then he adds: "Despite a new burst of youthful energy and enthusiasm for Detroit, no one can look out and see a point at which property values, income tax revenues and population stop declining."

A Sunday column by Rochelle Riley of the Detroit Free Press also raised the prospect that the appointment of an emergency manager may be inevitable. Unlike Finley, though, she was astute enough to make at least passing mention of a provision in the emergency manager law signed by Gov. Rick Snyder earlier this year that allows for another approach.

Instead of imposing an outside manager on the city, the governor could enter into a consent agreement that gives local officials many of the expanded powers of an emergency manager. The city would have to provide a written plan of action and then abide by it. The one big difference between that approach and the imposition of an emergency manager, explains analyst Bettie Buss of the nonprofit Citizens Research Council, is that, even under a consent agreement, the city wouldn't have the power to void established union contracts. However, once those contracts do expire, the city would have the authority to unilaterally set wage and benefit levels without having to negotiate with the unions.

There's also a wild card in all the talk of inevitability that, as far as we can tell, only MT columnist Jack Lessenberry has picked up on. As Lessenberry notes elsewhere in this week's issue, the coalition called Stand Up for Democracy is collecting signatures for a proposed ballot measure that, if approved by voters, would void the emergency manager law.

If the petition drive is successful, that measure would be on the November 2012 ballot. But the immediate effect, if it does qualify, would be to put the current law on hold at least until voters have their say, according to Detroit attorney Herb Sanders, who is directing the ballot drive.

Slightly more than 161,000 valid signatures are needed to qualify the measure for the ballot. According to Greg Bowens, spokesman for Stand Up for Democracy, the coalition has already gathered more than 80 percent of the signatures needed, and plans to have all the names required by Christmas.

Sanders is of the opinion that, if the ballot measure is approved by the secretary of state, not only will the law be put on hold, but any managers already appointed would lose their authority. That, however, is not a certainty. As Sanders points out, in terms of this issue, we are sailing into uncharted legal waters.

Although Detroit is currently the center of focus, how this issue plays out matters throughout Michigan. As Buss notes, local units of government across the state are dealing with the same problems that have driven its largest city to the brink of insolvency. Lost revenues due to high unemployment and the collapse of the housing market, coupled with reductions in state revenue-sharing funds, have put most in a precarious position.

Despite that, though, what isn't an option for Detroit at this point is the filing for federal Chapter 9 bankruptcy. Just last week, in the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history, Jefferson County, Ala., took that extraordinary measure in an attempt to deal with the burden of more than $4 billion in debt.

Pennsylvania's capital city, Harrisburg, also filed for bankruptcy recently.

However, according to Buss, the only way for a Michigan municipality to file for bankruptcy is for an appointed emergency manager to initiate the proceedings, which would then have to be approved by the state before moving forward.

In other words, that ain't going to happen — at least not in the foreseeable future.

Also gaining headlines last week was the claim by Bing — finally taking up an issue long raised by Detroit Councilwoman JoAnn Watson — that the state owes Detroit $220 million in revenue-sharing that was promised by then-Gov. John Engler back in 1998 in return for the city reducing its income tax rates. (For more details on this issue, see this week's "Stir it up" column by MT's Larry Gabriel.)

No one is denying that the promise was made. But that pledge doesn't have the force of law, and so any obligation the state has at this point is a strictly moral one. There's apparently no turning to the courts for help. And, given the state's problems balancing its own budget, the political likelihood that a Republican-dominated Legislature would meet that obligation now, according to Buss, is "slim to none. And probably closer to none."

So, what's the answer?

Buss lets loose a deep sigh when we ask her that question.

"I wish I knew," she says. "I think we are all struggling to figure out a permanent solution."

In other words, no matter who it is that ends up calling the shots for the city of Detroit, things are going to get much worse before they get better, and even the most optimistic view is that the prospects of reversing a downward spiral 50 years in the making remain a distant hope.