Never let it be said that baseball is "just a game," at least as it relates to Toni Stone.

For Stone to step into the batter's box or make a play at second base was to overcome overwhelming racist and sexist obstacles that existed in mid-20th century America — baseball no exception. Jim Crow was a frequent teammate, as she traveled the country during the 1953 and 1954 Negro League seasons.

Born in 1921 in St. Paul, Minn., all Stone ever wanted to do in life was play baseball. Her parents, urging a career as a teacher, nurse or secretary, objected to her sporting ambitions. Eventually they acquiesced and let her play on a church team as a kid.

As a teen and young adult, working odd jobs to pay the bills, Stone joined several loosely organized, semi-professional teams in Minnesota and in California after she moved there 1943. She was often viewed by fans as a novelty, but that got ballpark seats filled, and that meant revenue to league organizers.

After Jackie Robinson broke the major league color barrier in 1947, African-American players trickled out of the storied Negro Leagues and into the majors. That meant openings for more players, including Stone.

She signed first with the Indianapolis Clowns, where she replaced Henry Aaron at second base when he went to the majors. Her second, and last, Negro League season, she played for the Kansas City Monarchs.

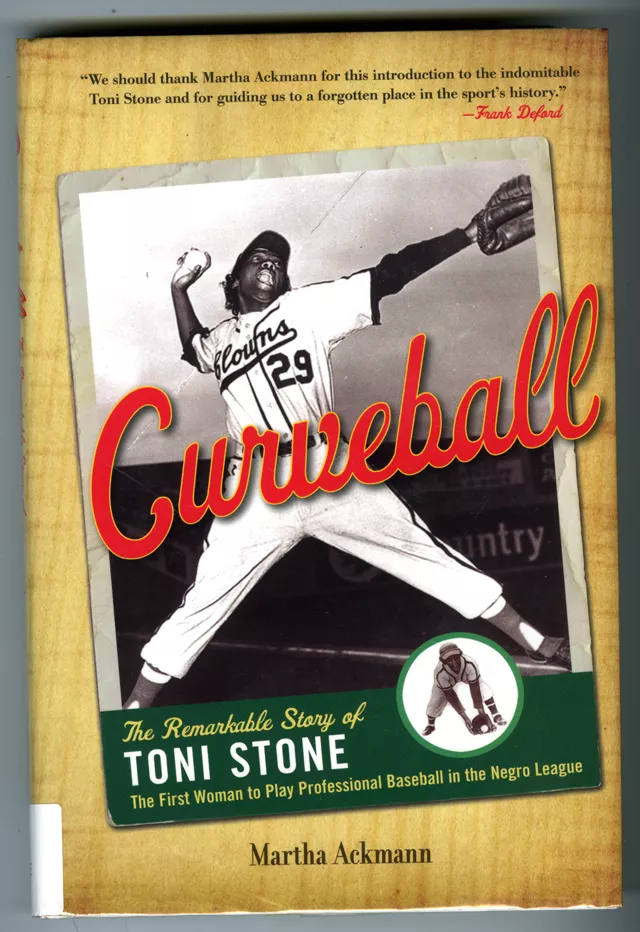

Stone's life and career — from neighborhood pickup game to cross-country barnstorming to obscurity in retirement — are aptly recounted in Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, the First Woman to Play Professional Baseball in the Negro League (Lawrence Hill Books, 274 pp., $24.95), written by Martha Ackmann, a senior lecturer in gender studies at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts.

The author spoke with Metro Times about Toni Stone, the Negro Leagues and what they mean to America.

Metro Times: Your first book, Mercury 13 was about women who secretly trained as astronauts in the early days of the U.S. space program. How does Curveball follow that?

Martha Ackmann: I write books about women who have changed America. When I went about searching for a topic for my next book, I knew I wanted to write about sports because I think sports are a great window for looking at American culture.

MT: How much of researching and writing the book was contextualizing the Negro League?

Ackmann: Because the book is both about Toni Stone and the times in which she lived, the other story besides her own I was trying to tell is the story of Jim Crow America, specifically through the lens of Negro League baseball. For example, I wanted to talk about Jim Crow conditions that Negro League players faced when they traveled around the country. Certainly there were Jim Crow restrictions all over the country but particularly in the South. So I talked about what would happen when players tried to get a meal in Washington, D.C. Henry Aaron reported that one thing he would never forget was the sound of dinner plates crashing. Some restaurants would serve black players but then they wouldn't wash the dishes; they would be so disgusted in their racism with black men coming to eat in their restaurant that they would break them instead.

MT: Did one detail hit you more deeply than others?

Ackmann: I was familiar with Jim Crow, eating conditions and lodging and traveling across the country, but when I read that black fans in New Orleans had to sit behind chicken wire, that was an indignity that was very, very disturbing to encounter.

MT: What kind of Jim Crow conditions but also sexism did Toni Stone face?

Ackmann: Sometimes when she pulled up to a boarding house or a hotel in the South, the 28 guys would get off the bus and she would be the only woman. The proprietor would look and say, "You must be a hustler or a prostitute," and direct her to the nearest brothel. Toni eventually had no other choice. She would have to stay there. She said, in her words, "These were good girls." I think she saw something of the outcast in them that she felt herself as a marginalized figure. Surprisingly to her, the good girls gave her a place to stay and laundered her uniform and sewed padding into the chest of her uniform so she could take hard throws to the chest, and eventually she built up a network of brothels where the girls would meet her sometimes in a car and take her to the brothel and show her the respect that she didn't find elsewhere.

MT: Did you find inspiring as well as disturbing stories?

Ackmann: I tried to get at the truth, and sometimes the truth cuts that way to be both disturbing and fascinating in the same way. I think it's very important to get down that kind of documentary evidence to try to be a witness to history — especially a history that not a lot of people know about a woman who wanted to play America's game.

MT: What were her Detroit experiences?

Ackmann: She played in Briggs Field [later known as Tiger Stadium], that was one of the many big, big stadiums, like Yankee Stadium and Comiskey Park in Chicago. I think she always really loved playing in the big stadiums, and it wasn't too far from her hometown. She was very familiar with the upper Midwest, coming from St. Paul. I think Detroit in the late '40s and the early '50s was a pretty great place to be playing Negro League ball. There was a lot of support and they were always packed games where she felt she got a lot of exposure.

MT: Did Toni Stone always play second base?

Ackmann: As a kid she played every single position. She was such a phenomenal athlete. I remember interviewing people, players who played against Babe Didrikson Zaharias [a noteworthy female athlete who was best known as a golfer but also played semi-pro baseball in the 1930s], they said, "Babe was a good player, and Toni Stone was a really good player." As a kid she played everything. She got knocked out once when she was catching and she said, "OK, I've had enough of that." She played a lot of outfield but by the time she was in her late teens to early 20s she ended up on second base.

MT: Your book was written more than a decade after Stone died. Did this limit how far your research and writing could go?

Ackmann: That was a great sadness for me because she was such a wonderful storyteller and had such a great flair for language and knew what the good stories were. So no. I started long after she had passed away but one of the things I did was that I tried to find every single audio or video tape that I could possibly find both to hear the tenor and quality of Toni's voice but more importantly how she related things. I was lucky to find a lot because of the great and good generosity of men who belonged to the Society for American Baseball Research.

MT: If you could go back in time, what would you ask her?

Ackmann: I've never thought of that before. I would dearly love to sit with her in that beautiful little Victorian home that she had in Oakland, Calif. I think I would try to get at what kept her going in the face of such opposition. How did she manage to continue to pursue what she loved most, what was the fire in the belly that really kept her going? I'm always interested in those questions about persistence.

MT: Who do you think the audience is for a book about a women playing in the Negro Leagues?

Ackmann: I feel like I'm always in my books writing stories about social change in America, and about, in particular, how women have faced inequity especially when they have a very uncommon dream. I tried to tell that story in a way that's going to be interesting, I hope, to a broad audience so they learn something about American women's history, they learn something about sports, but I hope they also learn something about the struggles for equal rights in our country.

MT: So you chose the texture and context of the civil rights movement to be part of Toni Stone's story.

Ackmann: She's bucking the system. She's refusing to be silenced. She's refusing to be put down in the early 1950s, before Rosa Parks refuses to give up her seat on the bus. I see her as a part of that continuum of making a way for the civil rights movement to come.

MT: Would she have described herself as a civil rights heroine?

Ackmann: No, she wouldn't have. I think it's a great tragedy that in the late '50s and early '60s that she couldn't quite see what she had done as part of this larger fabric.