Maki: Novelty records were very popular. At that time, songs like “Hamtramck Mama” sold so well that the jukebox operators who had these small record labels in Detroit wanted to keep them coming, to make more money by issuing more crazy stuff like that “Detroit Hulu Girl,” which is just a scorcher of a record for 1940. It’s like this-side-of-rockabilly music.

MT: Like rockabilly music from the ’30s.

Maki: Yeah.

MT: Slap bass, crazy steel guitar … Also, one thing about the York Brothers, they weren’t like other “brother duos” like the Blue Sky Boys, the Monroe Brothers, the Louvin Brothers or the Delmore Brothers, but the York Brothers had a very bluesy, it wasn’t the high lonesome harmony thing, it was more of a mountain blues kind of approach, really raw and very exploratory with the electric guitar early on. And they remain that way for their entire career. Always very unique.

Maki: Yes. Very earthy types of songs. Most of the things they did in Detroit for the independent labels — I’m speaking mostly of Mellow. They recorded more than 30 sides. Which is just a stunning number for an independent record label before the war. The York Brothers wound up going to join the Navy in early ’44. So between ’39 and ’43, they cut a stunning number of originals, and I’d say most of them are wonderful, off-the-cuff performances that show that these guys really knew what they were doing and they were at the top of their game. A very professional-sounding duo. It’s no wonder they were so popular in Detroit.

MT: Another interesting thing about the York Brothers is the sort of tawdry, double-entendre lyrics that they specialized in, this became a thing in Detroit. Certainly, in the ’40s and ’50s, it was a popular trend in general everywhere, but I’d argue there was much more of it here, it was much more gut-bucket, low-down. Fortune issued an album that spotlighted this genre called The Tattooed Lady and 11 Other Sizzlers.

Maki: I think the answer to that has to do with the record labels. Mellow was operated by a guy named Edward Kiely, and he ran these music shops on the east side, and he also operated a jukebox route on the east side. And these novelty records were apparently getting the most spins on the jukeboxes. So the independent labels in town found that they could sell more of those types of records. And they had the artists record them. Now the York Brothers recorded more than 30 sides for Mellow, and not all of them are novelty records. A lot of them are “heart songs” and even more traditional-sounding songs. And some of the other artists who appeared on Mellow, which were just a handful, as far as anyone knows, they always had one side, at least, as a novelty-type record. And then the other side was something else.

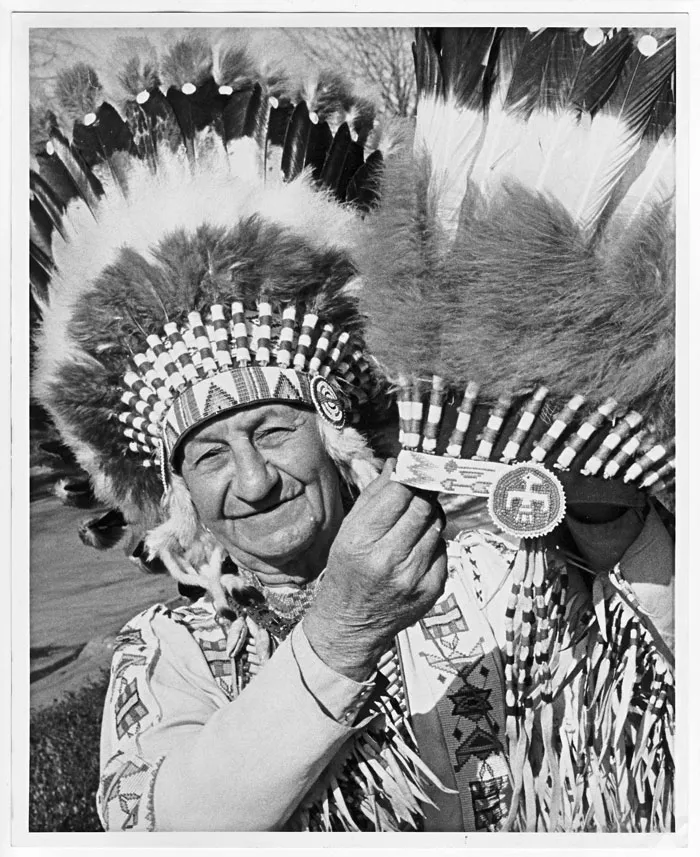

There’s this record by Chief Redbird, a novelty, called “They’re Gonna Hang Old Pappy Tomorrow,” cut in the late ’40s, I think 1949. It’s really special because Chief plays fiddle, but they also have, from what I can tell, two jazz musicians on this record. Bob Mitchell plays guitar and Bobby Stevenson, a jazz pianist, who used to work on the west side. They both perform on this record. And Bob Mitchell was a fellow who sort of fraternized with a lot of the country musicians in town. And Tommy Odom was one of them, and Tommy said he learned quite a bit from watching and listening to Bob Mitchell in the clubs. I think Bob Mitchell got his start in the 1930s playing in big bands.

MT: That’s one of the things that’s fascinating about the Detroit music scene is the cross-pollination of all kinds of different music and culture sort of coming together and colliding. I think it’s something that you hear. I would argue it’s one of the unique things you hear in Detroit hillbilly music. One of the things that makes it stand out is its originality. And a lot of that originality comes from this all these different cultures living among one another.

Maki: That record is also an example of the attention Detroit musicians put into their performances. You cannot get by in this town without playing at a certain level.

MT: Earl and Joyce Songer, one of the pioneering duos, very futuristic, they kind of crystallized that urban countrified sound, electrified, there’s an energy to the music, you can almost tell it was recorded in an urban environment in a way.

Maki: Yeah. Electrified mountain guitar.

MT: Courtesy of Joyce Songer, also known as Mimia Singo, who’s still with us, down in Tennessee. I know Joyce helped you a lot with her story and other stories about other musicians she worked with up here.

Maki: Absolutely. She was very kind and helpful. And just an amazing talent too, to be able to come into the country nightclubs in Detroit with her then-husband Earl and not only record several sides for Fortune, but get signed to major labels and travel the country and play on radio stations and different types of showcases. During the early ’50s, I can’t think of very many female guitar players playing electrified guitar at that time.

MT: I can’t think of any female lead electric guitar players at the time. And leading her own bands after a while? I don’t think she thought she was doing anything different, that was just what she did. She had a raw approach, but very skilled at picking. She was a childhood friend of Chet Atkins, and they certainly influenced each other a bit musically. Another somewhat forward-looking performer was Rufus Shoffner. His “Shotgun Wedding Blues” is pretty emblematic of his work. Characterized by some as “old-timey,” but it’s also futuristic in that he’s got that rockabilly slap bass along with a banjo and a fiddle.

Maki: Similarly, “That Old Heartbreak Express” by Buster Turner is an interesting record. When my research collaborator and friend Keith Cady was interviewing Buster Turner, he asked him about that record and Turner said that they carried an electric guitar player with them in the nightclubs in Detroit because they needed to be more versatile than just a bluegrass group. They needed to play waltzes and popular tunes of the day and that’s what people expected. So that record is basically a bluegrass group with an electric guitar. And there were a few other examples of this from the mid- to late ’50s.

MT: And it’s funny because one of the things that I love the most about “traditional bluegrass music” is how untraditional it often is, in that they’re not obeying all the “rules” that, later on, people sort of shackled themselves to. You’d never hear that now. You’d be thrown out of a bluegrass festival, in some cases, if you had an electric guitar. You have these neo-traditionalists trying to protect the history of it. But what makes this music you write about so hardcore is that, no matter what they’re doing, you can just feel that rawness and energy and experimentation.

Maki: Yeah. A lot of the records made at Fortune, like “That Old Heartbreak Express,” the label owner, Jack Brown, would just let the bands go. So what you got on the record was what the band sounded like in the nightclubs where they played. At the Fortune studio, he would just turn on the tape and let them go.

Craig Maki and Keith Cady will be present a book signing event, including a tribute to Chief Redbird starring Chief Redbird’s daughter and guitarist Al Allen, at 4-6 p.m. Dec. 13, at D:Hive 1253 Woodward Ave., Detroit; 313-962-4590.