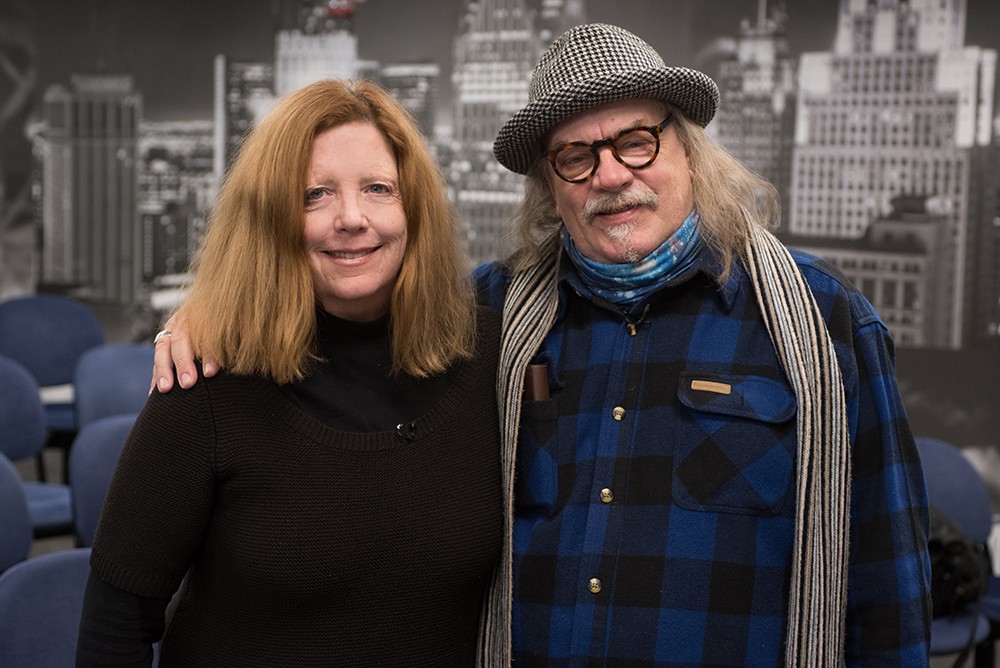

Two weeks ago, Robert "Jr." Whitall and his wife Shirley Owens — you can call her "Sugar" or "Sugar Mae," everyone does — got to touch the holy grail of their 19-year marriage. During a visit to Willie Mitchell's immortal Royal Studios in Memphis, the couple laid hands on "No. 9," the RCA microphone Al Green used to record virtually all his greatest hits, including "Love and Happiness."

"That's our theme song," says Whitall, who with Sugar publishes the Royal Oak-based, internationally-known music magazine, Big City Rhythm & Blues. "We played 'Love and Happiness' at our wedding."

Now their love has brought them a renewed, almost miraculous sense of happiness. Because when the radiation treatments that helped Whitall defeat prostate cancer left his kidneys damaged beyond repair, Sugar got tested so she could donate a kidney to someone who would then find a kidney donor for him. The process is called a paired kidney exchange, or "kidney swap."

Amazingly, unbelievably, the husband and wife were a perfect match. In her first-ever surgical procedure, Sugar, 62, gave one of her kidneys to save Jr.'s life in a 14-hour transplant operation last August at Henry Ford Hospital — avoiding a potential seven-year wait for an organ from another donor.

Now the couple wants to send thank-you (musical) notes to the hospital by promoting and co-sponsoring "A Sacred Night of Music Celebrating Living Organ Donors" on Monday in the Parliament Room of Otus Supply in Ferndale.

The concert — which will headline Detroit's reigning Queen of the Blues, Thornetta Davis; Calvin Cooke, the undisputed master of a unique, gospel hybrid performance style known as Sacred Steel; and metro Detroit duo and Acoustic Madness bandmates Bob and April Monteleone — is intended to raise awareness for the new living donor initiative at the Henry Ford Hospital Transplant Institute.

"This is the first of a series of concerts we hope to build on," Whitall says of Monday's show, also sponsored by the revitalized Ann Arbor Blues Festival and the transplant institute. "Maybe once a year we'd like to do a nice big fundraiser. What tied everything together is the fact that we all have had experiences at Henry Ford."

In Davis' case, her sister, Felecia, is on the waiting list for a double lung transplant. "So me and my family, we all know the agony of waiting on a donor," she acknowledged in a video message to Jr. and Sugar.

For Cooke, the parallel is even more remarkable: 14 years earlier, Cooke's wife, Grace, donated one of her kidneys to her husband as well — at Henry Ford.

Before Whitall's transplant, "I reached out to a lot of people who had gone through it [kidney transplant surgery] for a little coaching, to stem my fears," he remembers, speaking via FaceTime from inside an Airstream trailer while vacationing with Sugar in Sleeping Bear Dunes. "And Calvin was there. He called me every day. He said, 'Well, this is what it's going to be like. You're going to be taking pills the rest of your life. There may be some problems. But worry about your wife, because she did all the work! She gave something up!'"

"I told him, 'Calvin, we owe the hospital something," he says. "This is a great story, two musical couples are together still because of these great doctors at Henry Ford.' He said, 'I'm in. Anytime you do something, I'm in.'"

And so he is. "That whole staff I would go to see every week, they were excellent," recalls Cooke, who relocated from Detroit eight years ago to McDonough, Ga., south of Atlanta, to treat his kidney to warmer weather. "Those were the best doctors and group of people I've ever worked with. After I saw how serious they were, how the nurses knew you by name and made you feel comfortable, I knew I was being well taken care of by Henry Ford.

"I realized that where God sent me was the best place, and I've never forgotten it."

Sacred Steel is a stylized strain of gospel featuring lap and pedal steel guitars, spawned from the House of God Pentecostal Church in Nashville. "In our organization, the steel guitar is the main instrument," Cooke explains. "All of us were playing gospel, strictly gospel music, but now things are changing because a lot of us have been mixing blues into what we do."

The self-reported good health of all four transplant participants — Jr., Sugar, Calvin, and Grace — underscores the value of living organ donors. As opposed to organs from deceased persons, living donor transplants last longer, can be timed for the optimal health and convenience of both donor and recipient, and avoids the years-long wait for a matching organ from the national donor registry.

Jr. — there is no "Sr.," as Whitall adopted the blues-rooted nickname as a tribute to such musicians as Junior Wells and Robert Jr. Lockwood — hopes their double-barreled love stories will encourage more Detroiters to consider becoming living organ donors. He says that when he first met Sugar, he thought she was so beautiful that she had to be a doctor's wife. "The music brought Jr. and me together," adds Sugar. "We have a lot in common."

They believed from the start that they were made for each other.

Who could have known how right they were?

"A Sacred Night of Music Celebrating Living Kidney Donors" takes place from 5-9 p.m. on Monday, June 11, at Otus Supply, 345 Nine Mile Rd., Ferndale; 248-291-6160; otussupply.com; Tickets are $20 in advance here, $25 at the door.

Jim McFarlin, a frequent Metro Times contributor and kidney transplant recipient on Nov. 18, 2011, is a freelance writer based outside Chicago.

Get our top picks for the best events in Detroit every Thursday morning. Sign up for our events newsletter.