Joe Bernard started his career making cutting-edge, experimental movies, scratching and abrading footage by hand, marking the film frame by frame, treating it like a painter's canvas — often implanting provocative poetic texts. But for the last decade, he's been painting collages that capture the poetic vision that flickered by in the films. If you missed BASEDONATRUESTORY, Part 1, an exhibition of his latest work recently on display at the Macomb Center, you should see the 32 new paintings of Part 2 that are at the Center Galleries: Each glistens like a radioactive television set or a maverick movie frame that slowly reveals itself. Still dependent upon the radical film model, the new paintings now achieve, formally and aesthetically, their own being.

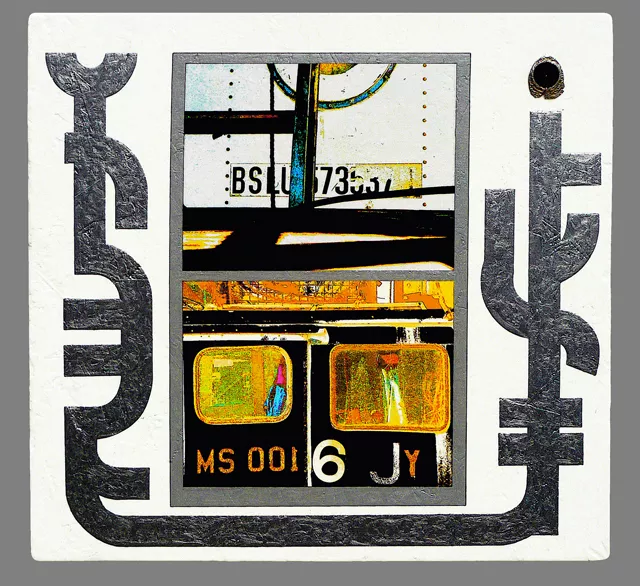

Bernard's multilayered, 2 feet-by-2 feet collage paintings, supported by quarter-inch oriented strand board (OSB is itself a wonderfully weird hybrid of plywood and recycled woodchips) are the children of invention: They answered a need and filled a void. Bernard's works are an amalgam of manipulated photos, poetically charged words and letter fragments, symbolic objects and abraded paint. The story of their evolution is a history lesson about the artist and our near past.

Before turning to collage paintings, Bernard was an "experimental" or "alternative" filmmaker. He made more than 100 silent films in Super 8, a consumer format introduced in 1965 and mostly — but not always — used for home movies. His instructor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago was the famed avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage, whose lyrical film works placed the physical strip of film at the center of his process. Brakhage literally glued leaves and other detritus to the film, which became the medium of the work and a metaphor for consciousness. To Brakhage and those like him, film was mind.

Bernard's own film works followed the path of Brakhage and others who, in a revolutionary moment, realized they could make a movie independent of the shallow, predictable, knee-jerk narratives that characterized Hollywood at the time — and do so by a totally independent process, without a film crew. In fact, following the tenets of "pure cinema," narrative or storytelling were rejected in behalf of the pure experience of effects of the medium. In the larger artistic scope, storytelling was in general suspect, becoming a target of most avant-garde artists, whether painter, poet, composer or filmmaker.

And so film replaced the painter's canvas, or the poet's notebook, as a supporting surface for expression of all sorts.

Asked about his artistic processes on film Bernard says: "All were silent. Emphasis was on light, color (except those in black and white) and movement. Text was used in some of them. (I would film pages that I had typed on). As so many others have done, I used many tools to disrupt the emulsion: sandpaper, bleach, permanent markers, pins, files, fingernails, film cement, etc. Fast editing would also alter camera imagery. Rhythm was something I could almost hear through my eyes (not like hearing, but being able to watch the hands of musicians at work.)"

On his website (josephbernard.com), clips of his films from the late '70s and early '80s reveal a hybrid of styles that are remarkably "musical," composed of abstract slashes of light and color, scratches and morphing cellular-like structures and collaged photos. Like abstract painting, Bernard's film did battle with representing reality as it looks through human eyes or even through a "straight" camera. Though not at all dated-looking, they represent the artistic climate of the time and, after the deluge of new video technology, began to seem somewhat passé.

Asked why he gave up film, Bernard replies: "My version of 'film' had all but disappeared. Kodak had cut back on their stocks (Kodachrome, Ektachrome, Tri-X, Plus-X) until they couldn't easily be found. Labs went out of business, so if you did find stock, it couldn't be processed. Dealers stopped handling Super 8 and 16 mm cameras, editing equipment, projectors, even bulbs. I hoarded these things — but without a trustworthy lab, mailing raw camera footage off to unknown quarters became a crapshoot. Video accelerated the demise of small format film, and video's early (even current) resolution was far from desirable. Film was a physical, manual thing; the editing was done with scissors and glue (collage), it had a look, a smell, a sound and a feel. Anything else would be like a blow-up/rubber replicant."

Bernard's personal artistic dilemma reflects a larger cultural shift. Since the early '80s and the beginning of the transition to digital media, the apparatus and material of filmmaking have become increasingly hard to come by — but not the impulse to build objects that physically exist for some duration of time, Bernard eventually retrenched and invented the extraordinary forms that we see now.

It helps explain why each new painting is like a single frame of his experimental films, compressing the rich and strange activities of consciousness into lyrically wrought, mandala-like images: enigmatic photos jammed with words; fragments of letters decorating the margins of the paintings like illuminated Islamic manuscripts or Cyrillic letters, their inscrutable meaning just out of reach. Some have letters that run on into words, composing poetic lines that make momentary sense then retreat into the surrounding surface. Some are made of the detritus of the day: seed pods, dried flowers and leaves, such nightmarish words as Somalia, diurnal beer cans flattened into gorgeous random shapes, beer caps arranged in grids. Some, composed of photos of body fragments, evoke the erotic, though others, such as "The Visitant," read like sci-fi movies, all collectively read as an ongoing, epic poem.

With their pulsating high-gloss finish, suggestive of the hyper-reality of HDTV, there is an overall sense of the ineffable, just-out-of-reach reality of our time. Bernard has given up much in his work. He gave up the fourth dimension of motion pictures, the psychic and physical experience of the passage of time, and instead has composed highly charged objects that read simultaneously as cryptic or ancient signs, and as emblems of consciousness. He has always been a bardic presence in our community but with this latest work Bernard has created inscrutable, timeless masterpieces awaiting engagement.

In a sense, Joseph Bernard is still making moving pictures.

Based on a True Story! (Pt. 2) is at the Center Galleries of the College for Creative Studies (of which Joe Bernard is a retired faculty member) through Dec. 18; gallery open 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday, at 301 Frederick Douglass, Detroit; 313-664-7806.