A period setting lends aesthetic cover to a standard horror story in The Black Phone, but the level of distinction offered feels awfully thin. Set in suburban Denver in 1978, Scott Derrickson’s mystery-driven, lightly supernatural kidnapping thriller feels better undergirded with regard to evoking the details of its setting than it ever does in its narrative’s swerves and arcs. As a result, its familiar, quite straightforward tale — adapted from a 2004 short story by Joe Hill — feels both unsurprising and oddly baggy as it progresses in measured, at times finely calibrated movements toward its story’s close. Its best moments far outstrip its worst ones, though, resulting in a work that feels at once fussily prepared and a bit undercooked, with artistic attention and running time too often feeling misspent.

But those flaws aren’t quite enough to sink it. Thankfully, the film feels salvaged by the well-trodden nature (and accompanying strengths) of its source material. One of the benefits of working in genre is that the bones of a story tend to be inherited, lending support to artists who falter in realizing a vision while furnishing viewers (or readers) with a kind of promise. “Just wait,” such stories often seem to say as they leave cues for those approaching them; with a series of knowing, expository gestures, they remind audiences just what it is they came for even when the goods come late.

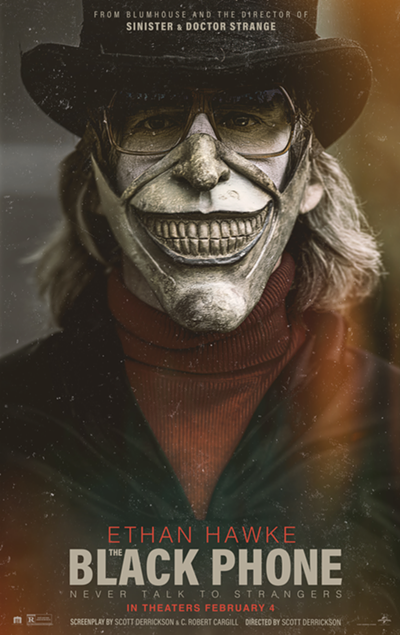

In this case, the premise and its attendant pieces which follow are simple enough, though the film takes its time elaborating them. Basically: after a shy and bullied boy, Finney (or “Finn,” played by Mason Thames), and his fiercer sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw) lose schoolmates to a mysterious child abductor known only as the Grabber, Finn becomes the masked figure’s latest victim. As the town slips into disarray as the killer (Ethan Hawke) continues his foul work, Gwen — who experiences mysterious, seemingly communicative dreams — works to find Finn, who meanwhile hopes to break out of his barren basement cell. Within that drab space, he receives mysterious, haunted-seeming calls from a disconnected wall phone — offering hints and clues toward his survival, stemming from some barely clearer source. There’s a pleasing, just-sufficient neatness to this structure, whose two prongs close like a pincer throughout, grasping a story with a plainly inevitable endpoint that can only pan out in one of two ways.

Despite this, Derrickson’s own pretense as a director creates some static. The road to Finn’s kidnapping, for instance, feels oddly loopy, with extended sequences of his school and home life (both abusive, thanks respectively to bullies and an alcoholic father) alternating with winding walks home with his sister or, more rarely, some new friend. Confrontations in bathrooms, hesitant flirtations, and coyly written conversations about the day’s pop culture all feature, working in a nostalgic register scanning less as a picture of the time than retrospective fantasy à la Stranger Things. In keeping with this tendency, most every pre-abduction frame on screen is pushed through some sort of tan filter, not quite rich enough for sepia. Certain colors are pushed within it: the primary reds and blues of baseball uniforms, for instance, and the bolder, look-at-this-outfit patterns worn by some onscreen. Such techniques for rendering the ’70s (though it’s often done with a more gold- or amber-tinged palette) feel aesthetically lazy as shorthand, familiar from the Fargo TV series and BlacKkKlansman (less guilty) and plenty else, nodding vigorously in the direction of a time. Still worse, these moments devoted to establishing the film’s world feel plodding in their dull secretion of mundane detail. In works this nods to and even calls out — like Tobe Hooper’s original Texas Chainsaw Massacre — wasting long stretches on such stuff would be unthinkable: not solely as a matter of artistic disposition, but due to artists working on celluloid and on a tight budget. The best cases for aesthetic nostalgia lie in just these sorts of details.

In scenes of Finn’s confinement, though — which alternate with less focused sequences outside driven by his sister and a pair of fumbling cops — many of the distancing flaws present in Phone’s first act fall away. To the film’s benefit, the basement within which the Grabber has confined Finn isn’t shot with the same nostalgic register as stuff outside. Instead, it’s mostly rendered in a fashion that looks both unremarkable and basically modern, shot in low blue-green light — free, in other words, of distracting aesthetic veneers. Within that space, the story’s rhythm is measured, suspenseful, and just a little unpredictable as Hawke’s killer enters periodically to toy with Finn conversationally and offer scant meals, the only details offered over their periodic talks proving more than a little opaque. In each instance, he enters the cell wearing a strangely bifurcated devil mask, one whose available variations offer a certain wealth of expressive potential. Taken alongside Hawke’s gravely speaking voice, his character’s just-restrained sadism, and the strangely eager, childlike air of need he expresses towards his victims in conversation (as an actor, he most always speaks with a certain earnestness), his presence generates a consistent chill even in stiller moments. Benefitting from a focused tension between two figures (even when one is absent), these basement sequences are the film’s best part.

They’re not spotless either, though, and the film’s struggle to navigate its own details at times hurts it even amid these scenes. (Their sparseness seems to be enabling; there’s less to sort within them.) Still, Derrickson seems ill at ease with the confinement scenes’ natural strengths, spattering them with jump-scare moments of macabre spectacle despite the fact their quieter, less narratively forced moments feel considerably more rewarding. This sense of isolation may be narratively confining, but it protects the film and director from their own worst faults, saving each of them from themselves.

Film Details

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, or TikTok.