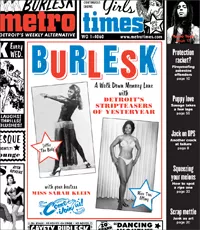

They called her The Body.

She was built like a double order of pancakes — sweet and stacked. The only light in the room bathed her as she emerged from a thick velvet curtain, incandescent, platinum hair piled high on her head. As the band struck up a slow, seductive wail, her intricately beaded gown glimmered with each step. By the end of the tune, the dress was gone, and she wore little more than heels, a few strategically placed rhinestones, and a smile.

Her playground was Paradise Valley, the now long-demolished entertainment district on Detroit’s old Lower East Side, and her signature shimmy held sway in that earthy realm. She rubbed elbows with Louis Armstrong and Aretha Franklin, she dined with Dinah Washington and strutted alongside Billie Holiday. When she and her Harlem Globetrotter husband Goose Tatum lived in a villa in Cuba, she was chummy with Fidel Castro. And one notorious racketeer in Indianapolis was so was taken with her legendary proportions that he built an entire club just for her, naming it the Pink Poodle. Many times she was issued proclamations by City Council, noting her significant contributions to Detroit’s thriving entertainment culture.

Lottie The Body was — is — the Motor City’s most famous exotic dancer, an ecdysiast for the people. Almost 40 years later, she hasn’t lost an ounce of charm — and a whole new generation of burlesque neophytes could learn a thing or two from her.

Burlesque is back — this is the headline you’ve probably read in every publication from Podunk Weekly to The New York Times. Within the past five years, the new burlesque movement has exploded across the country, with young women picking up boas in droves in an attempt to re-create the classic stripteases of yesteryear, often with a modern twist.

As the popularity of the movement careens toward a critical saturation, attention is now turning toward the past as well as the present, with the burlesque stars of yesteryear finding themselves in the limelight once again.

Recently, HBO aired the documentary Pretty Things, in which filmmaker Liz Goldwyn tracked down and interviewed such burlesque legends as the sharp-tongued firecracker Zorita and the legendary Sherry Britton. Exotic World — the world’s only burlesque museum, located in the middle of the Mojave Desert — has grown from a relatively obscure roadside attraction to one that grabs national headlines with its annual Miss Exotic World burlesque pageant. The museum is dedicated to reuniting the living legends of burlesque, and functions as an emotional and vital liaison between the new performers of today and the tassel-twirling starlets of decades past.

It’s a strange and moving phenomenon; many of these legends have been forgotten by society, cast aside as their youthful beauty faded. Their days of fame, glitter and Champagne are long gone, preserved in a few grainy photos and perhaps a withered feather boa. Some of them are fondly reminiscent and a few are just plain bitter — after promoters and agents cashed in on their curves, leaving the performers themselves shortchanged.

Then there’s the brand new generation of fresh-faced ingenues — frequently sporting numerous tattoos or rainbow-colored tresses — who are completely entranced by these women, hoisting them atop glitter-encrusted pedestals as their divine muses. But, sadly, as we creep forward in the new millennium, those aging muses continue to disappear, one by one.

Detroit is fortunate enough to have two living legends of burlesque still kicking. Here are their stories.

The Body

Lottie “The Body” Graves is one of the most colorful figures in the city’s history. Known as Detroit’s answer to Gypsy Rose Lee, Lottie’s fabled, glittering past is interwoven in the rich fabric of the city’s musical heritage and the musicians who built it.

Even today, Lottie hasn’t lost a bit of her trademark charisma, bursting with joy and vivaciousness. Like a true showgirl, Lottie does not reveal her age; but anyone who saw her hoofin’ in the acclaimed documentary Standing in the Shadows of Motown knows she’s still got it.

Opening the door to her condo near Lafayette Park, Lottie squeals “Hello, my boo boo!” and offers a warm hug. This, apparently, is her standard response for a first meeting.

Her gray and black hair is short and spiky. She wears a bright red tank top that says “SEXY” in big bold letters. The hallway is adorned with the framed proclamations, recognitions and honors Lottie’s received from local organizations and city and state governments. A sepia-toned painting of a sultry Lottie in her heyday hangs next to photos of her family.

Born in Syracuse, N.Y., Lottie was schooled in Brooklyn and started her professional dancing career when she was only 17. Classically trained, she soon found herself traveling across the country. She says she landed in Detroit around 1960, first arriving at the legendary Twenty Grand nightclub on West Warren Avenue — one of the most popular nightspots at the time.

“I fell in love with Detroit,” Lottie says. “It was such a warm place, so many beautiful places to go and see and do. The music was my number one love, though.”

She performed with the best. As Lottie rattles off the list of musicians she co-starred with over the years, it sounds like a wing from the Hall of Fame: T-Bone Walker, B.B. King, Billie Holiday, Maurice Taylor, Solomon Burke; at places like the Flame Show Bar, the National Theater on Monroe Street, the Brass Rail on Adams, the Elmwood Casino in Windsor — all now reduced to flickering memories, decaying ghosts or weedy parking lots.

Back then, strippers preferred to call themselves “exotic dancers,” a term that evoked an image of class and glamour. Burlesque generally referred to the vaudeville shows in theaters, which included comedians and chorus girls along with strippers — in other words, the package deal. There were also shake dancers, who shook but didn’t strip.

But the Body? The Body was her own category.

“Lottie was a star in her own right,” local historian Beatrice Buck recalls. “Some of them just took their clothes off, and Lottie was not that. Lottie was a dancer, and therein lies the difference.”

Motown giant Martha Reeves, also Lottie’s neighbor and friend, says, “She held her own. Lottie had skills that were superior to all of her competitors. She outdanced them all. She had body movements that only she could pull off, and very elaborate costumes. And I know she can still dance, and does a high kick that shows a lot of young ladies down.”

Lottie’s mastery of the tease led her to glamour, glitter and luxury. “Exotic dancing was classy,” Lottie says. “It was the top of the shelf, the Champagne of dance, with some of the most gorgeous women in the world, like Tempest Storm.

“I met her in L.A. and we worked together. You made very good money, and you weren’t looked down on. When you went into a hotel they brought in your luggage and there were flowers and Champagne in the room. They didn’t look down on you as a prostitute because you didn’t expose your body, you weren’t giving yourself away. You were representing yourself as an artist — it was show business!

“I’d travel from club to club and star with big artists. I had a lot of beaded long gowns. All my undergarments had rhinestones that were made in Montreal. I had this rhinestone bra and G-string, and when I hit the stage it would just light up.”

She gestures up toward imaginary stage lights, eyes twinkling.

“And on top of that was ostrich feathers — and feathers, and feathers, and feathers,” Lottie says. “And then one costume was all white fox that would just wrap around me over and over.”

But despite her star power, racism sometimes tarnished her charmed life, especially in white clubs. “It was never shown, but you could feel it,” she says. “I ignored it. And you know, anywhere you go in the world, you’re going to find it. So you overlooked it, because you’re the one up on that stage and they’re looking up at you, and if they don’t like it they can leave.”

One time when she was performing outside of Boston, another dancer’s boyfriend refused to acknowledge that Lottie, a black dancer, was headlining the club. “So all the gangsters in Boston told him he could either accept it or pay them their money back,” she says.

“I was in Madawaska, Maine, and I think I was just about the only black person they’ve ever seen. I was walking down the street and the little children would say, ‘Mommy, look at the walking chocolate bar.’” Instead of bitterness, the moment triggers a flurry of infectious high-pitched laughter, as Lottie slaps her thigh.

The giggles continue as she recounts stripping bloopers. “Oh, my G-string popped. Yes, my bare hiney was out. And then there was the time my ponytail came off ...”

Inspired by all the reminiscing, Lottie disappears to dig through her closet. She returns with a billowing mass of ash-grey and white chiffon. It’s a sheer overcoat with armholes that snap around the neck. She demonstrates how to wear it, slipping it over her shoulders and launching into an impromptu dance routine in her living room.

She spins and the gown blossoms into a giant swishy flower of movement. Lottie starts up her own accompianment: “Da da, da da, ba dum dum da da!” She twirls, she winks coquettishly, she shimmies her shoulder and flutters her pointed toes with the elegance and effortless poise of a professional.

When she removes the garment, she sternly points with a manicured finger as she lectures sweetly, “You never throw your stuff on the floor.” Then she saunters off her makeshift stage, the filmy fabric clutched in one hand, trailing a wake of chiffon behind her.

Ellington’s Ecdysiast

Toni Elling was born and bred in Detroit. At 18, she was selling flowers at the swanky Gotham Hotel, and later went to work for the phone company as an operator. But after nine years there, she says racism prevented her from being promoted. So, in 1960, she became a stripper — at the age of 32.

Toni Elling is her stage name; she asked that her real name not be used since she now works as an aide in an elementary school. She’s not ashamed of her past — she’s quite proud of it — but worries that others may not see it the same way, given the negative connotations some associate with stripping today.

The midsummer humidity is unbearable, and Toni’s home on Detroit’s West Side — the decor monochromatically cream and white — is sweltering. Her collection of stuffed animals — she takes battered, abandoned ones from the street, cleans them up and gives them a home — are stationed in various corners of the room. Toni’s gray curls are pulled into a neat bun, and dots of moisture bead her forehead. She excuses herself to get a cloth.

“I’m not perspiring, I am sweating,” she announces with a regal tone and textbook perfect enunciation. “That’s what I used to tell my audiences: This is not perspiration, it is sweat because I’m working hard.”

She emerges from the kitchen with an armful of binders, and decades of memories spill out over the lacy tablecloth on her dining room table. She points to a grainy image of her svelte young figure, gracefully swirling across a stage in gossamer trails of white.

“There I am, at work,” she says, as nonchalantly as if she’d been behind a desk or a service counter. “There I am in all my unclothed glory. ... Oh, that’s me showing off my white mink. I did show off a bit sometimes. And that’s how Mr. Ellington saw me, with my silver wig on.”

Toni describes herself as Duke Ellington’s protégé — her stage name obviously derived from his — and refers to him as “a great friend.” She says Jackie Wilson helped her pick out her first “lobby,” or publicity still. Then she unearths a photo of herself in the Elmwood Casino in Windsor, chatting it up with Sammy Davis Jr.

“Here I am with my friend Sammy. We were singing,” she says, her voice sweet and thick with nostalgia. “He had Sundays off, so we went to go see Dinah Washington.”

Toni’s pathway into the world of striptease came in the form of her friend, a famously statuesque exotic dancer named Rita Revere. “She kept telling me, ‘You can do this, you can do it,’ and she told me how much money she made. But I was so bashful.”

She got over her shyness. Once she began working, she left Detroit and made Los Angeles her home base, traveling across the country and into Canada. Echoing Lottie’s sentiments, Toni stresses that dancers back then were treated with respect, like true entertainers.

Well, most of the time.

“Once a man grabbed my pastie, and he almost got killed because I was so upset. I was near the end of my act and he got up and reached up and snatched my pastie off! And I stood there and I patted my foot and I counted out loud to 10. You see, I was always known for my cool demeanor and my elegance, and I felt like calling him a bunch of you-know-whats. And, of course, I grabbed my bosom. And then he held it out and grinned. Oh, I felt like killing him!”

After leaving her traditional job because of prejudice, Toni still had to face it as a dancer. “I had a harder time than a lot of girls because of my blackness. It was very hard for a black stripper in those days. We weren’t paid what other girls were paid, and we weren’t allowed to work at certain clubs.”

She recalls a time when her agent tried to get her a glitzy job in Las Vegas. “I told her I can’t work in Vegas, they don’t want black people in Vegas.” Her agent persisted, so Toni went along with her to meet the manager of the club. He asked to speak privately with Toni’s agent, who responded that anything he needed to say he could say in front of Toni. The manager insisted, and finally he and Toni’s agent disappeared into an adjacent room. After a few minutes, voices began to escalate, and Toni heard her infuriated agent scream, “Toni is not a nigger!”

“Oh, she threw a fit, and she told him I was the best act she had,” Toni says of her agent. “She came storming out, and I just looked at her and said, ‘I told you so.’”

Still, Toni persevered with dignity, and doors began to open for her, and other girls. “I was a class act, and I ended up working at places black girls didn’t work at. They took a chance on me.”

Toni has pulled her bag of costumes out of the attic, and digs into a well-worn blue garment bag. Her boas, 30-some years old, are molting; limp ostrich feathers spill onto the cream-colored carpet. She pulls out each costume and describes the act it was designed for; she attached all the rhinestones by hand on these gloves, you see, and she made these pasties herself, and did she tell you about the first time she learned how to twirl them, causing her drummer to botch a beat when he first saw the spectacle? “I didn’t know you could do that,” he’d said. “Neither did I until just now,” she responded.

She holds the sequined pasties against her chest, the tassels dangling over her pink button-up blouse, and laughs.

Go Go ... Gone

Go-go dancing ushered in the death of burlesque. As the ’60s trickled into the ’70s, the Rat Pack and big band gave way to disco, Studio 54-style indulgence and sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll. Pasties were replaced by the pole, and subtle tease was abandoned in favor of more explicit displays. Dancers had two choices: Conform to the new standards — or quit.

As attendance gradually declined, many burlesque theaters were turned into movie theaters, usually showcasing X-rated films. Once associated with a grandiose spectacle, burlesque theaters became seedy, disreputable places linked with crime and grit, and were often pressured to close by city government.

“I got out because what was being done wasn’t to my liking: girls going all-nude, pole-dancing, contact with the customers; it was getting raunchy,” Toni says. “I guess people’s morals have changed.”

Lottie the Body feels much the same. “There’s no imagination, and they’re giving it all away,” she says of modern strip clubs. “When you had to go nude, I stopped. I couldn’t deal. The owners would tell you, ‘If you don’t take it all off, it’s over.’ And I thought too much of myself.”

After she quit dancing, Lottie worked as a receptionist for the city of Detroit for about a decade. At the same time, she began to emcee jazz shows, her bubbly personality providing the perfect segue from her dancing past. Through rich connections in the jazz community, she was never hurting for appearances. Dr. Teddy Harris helped her land a regular gig at Bomacs, where she stayed throughout the ’90s, and she also made appearances at Bert’s Marketplace. She’s retired today, and enjoys cooking, gardening and volunteering, helping out seniors at an assisted-living center.

As for Toni, she opened up her own boutique in Portland, Ore., selling boas, hosiery and pasties. She came back to Detroit after the death of her father, and soon after quit dancing for good, working odd jobs as a waitress, barmaid, switchboard operator and manicurist. “I adapt well,” she says of the transition from glamorous stripper to waitress, “but I missed it. I still miss it to this day.”

For a while, she even toyed with the idea of starting a class to teach girls how to strip in the classic fashion. But she couldn’t find a venue; everyone she approached balked at the idea. Except one.

“You ever heard of a fella named John Sinclair?” she asks, honestly curious whether anyone might know who he is. “Well, he was a radical, you know, and, oh, he thought it would be a hoot!”

Over the static of his cell phone, Sinclair says, “Toni? Oh, yeah, Toni, Toni Elling! I haven’t heard that name in a while. Yeah, she was named for Duke Ellington. She wanted to do something at the jazz center, I think. I remember her, because she was from the old-school [of stripping]. High-class, with the band ... not like they do now. Hey, give her my regards, will you?”

Sinclair can’t remember why the class never happened, but Toni says it was because one of his partners thought the idea too scandalous.

Few memories of burlesque remain in Detroit. The Twenty Grand and the Brass Rail are long gone. The last operating burlesque theater, the National on Monroe Street, closed in 1975 and has remained shuttered ever since, quietly rotting away while frenzied development goes on just footsteps away in Campus Martius and Grand Circus Park.

Most of the great exotics, both here and nationally, are gone. All neophytes have to cling to is a handful of senior women with a few dog-eared snapshots, maybe a collection of withered costumes smelling of mothballs, and hours of stories.

When told of the new burlesque movement, Lottie is skeptical at first. But she squeals with delight when shown a copy of Michelle Baldwin’s book Burlesque and the New Bump and Grind, a collection of today’s prominent burlesque performers. Flipping through the pages, she points and gasps gleefully at photos of modern starlets like Dita Von Teese, Kitten DeVille and Dirty Martini, commenting on the authenticity of the costuming and the diversity of acts.

“This is so delightful,” she says, beaming, flashing her thousand-watt grin. “I am so happy to see this! I wish I could see more of it.” Now she’s making plans to attend Exotic World next year, to meet these new starlets face to face, and maybe run into an old colleague or two.

Lottie thinks burlesque is just what this town needs.

“I would definitely like to see a classy exotic club in downtown Detroit, the way that the Brass Rail was. When they served dinner and there was a big show with a chorus line and comedians and a vocalist ...”

And, of course, the classic striptease.

“It was so classy, I really believe it would sell. The wives would come and drag their husbands. Before, when we were doing our shows, the couples would come and enjoy themselves; they loved it. And a lot of the wives would be watching, learning for their husbands so they could do it at home.

“I wish it would catch on. And it’s going to. Because everything comes around.”

One steamy July afternoon, Lottie is coerced into visiting the old National Theater, the once-opulent venue where she performed often, draped in the finest of costumes, surrounded by the stars.

Today, the building has the eerie beauty that many decaying Detroit landmarks possess; the ornate architecture has eroded with time and neglect, and the lower half is boarded up and chained.

Lottie grabs the padlock chain. “This was the main entrance,” she says. “And they used to be lined up down the block, with limousines and chauffeurs.” She’s handed her chiffon costume, and happily poses for pictures, twirling around on the sidewalk under the theater’s crumbling facade. Business suits walking toward the nearby Compuware building cast her an odd glance, and a homeless person walks up and asks her for change.

“I love the music and I love the people and there’s so much great hope here,” Lottie says of Detroit.

Standing in the shadows of the National, her hope hangs in the air, unanswered.

More:

Vamp camp

The Exotic World Burlesque Museum spans the generations.

Click tease

Curious about the new burlesque? Check out these Detroit troupes. (Full disclosure: The author has been involved with each, both past and present.)

Hell’s Belles Girlie Revue

www.hellsbellesdetroit.com

The Bottle Rockettes (formerly known as the Spagettes)

bottlerockettesdetroit.com

Causing a Scene Burlesque

www.causingascene.com