Stevie Wonder

Innervisions

Tamla, 1973

You can talk all you want about the history, mythology, technology and socio-political significance of Stevie Wonder’s 1973 masterpiece, Innervisions, but when it comes right down to it, only these things matter: It makes you dance like there’s no tomorrow, cry like no one’s looking and believe that there is hope even in the most desperate situation.

And once Stevie’s got those arms of universal funk, love and hard-won salvation wrapped around your brain and body, there is simply no forgetting his Innervisions.

“I know exactly where I was when I first heard it,” says Detroit-based musician Mick Collins, whose iconoclastic garage-rock band the Dirtbombs recorded a reworking of Innervisions’ centerpiece cut and highest-charting single, “Living For the City” on its recent CD, Ultraglide in Black.

“It was the week it came out. My brother and another friend of the family brought it to the house and put it on. When ‘Living for the City’ came on, it caught my ear immediately. Maybe I remember it so distinctly because a friend of the family was there and he broke down crying. His family was from Mississippi and it was pretty much his story.

“I never forgot the image of him sitting there with these tears streaming down his face.

“‘Living For The City’ is one of those things that anyone living in a rust-belt town knows someone that had those experiences that came from Alabama, North Carolina, Mississippi and they had a run-in with the authorities,” says Collins.

“When you get toward the end of the song, toward the spoken-word scene, it’s pretty in keeping with the people you meet in Detroit. And God help you if you meet those people first when you come here,” he adds, referring to a hustler who figures into the story.

With Innervisions, Wonder turned his ear toward a world of turmoil and was struck with what can only be described as divine inspiration. Innervisions is the sound of an artist at the peak of his powers. A bad-ass, funky, tender testament to the endurance of the human spirit. The story of America — black America in particular — told with clarion-clear streetwise poetics. He infused this all with a distillate of African beats (the classic hit “Higher Ground”) and Latin rhythms (the groovy “Don’t You Worry ’Bout A Thing”), gospel touchstones (the scathing “Jesus Children of America”), and R&B and pop.

Groundbreaking in his use of synthesizers, Innervisions’ myth/history has Wonder setting up his preprogrammed synthesizers in a circle during the album’s recording and moving from instrument to instrument chasing the perfect sound.

And he may just have caught it.

“Every time I hear it I get freaked out because of its genius!” enthuses electronic artist and Planet E label head Carl Craig of “Too High,” the album’s opening cut (and his personal favorite).

“No one has been able to touch it since. Not even Stevie.”

Craig is an architect of Detroit’s heralded electronic music presence worldwide — from his atmospheric-funky solo work as a producer and as leader of the electro-jazz all-star outfit, the Innerzone Orchestra, to his crucial role in birthing the Detroit Electronic Music Festival and running his own label, Planet E. In his work, the influence of Wonder, and Innervisions, is undeniable. When asked how the record affected him, he states simply: “It’s a loose template for my music.

“Stevie and Prince gave me and others who grew up in this and other economically challenged cities the faith that we can use our talents and make dreams come true, and remain in control,” he continues.

By 1971 Wonder had already spent almost half his life as a pop star toiling in Berry Gordy’s Motown hit factory (which had just pulled up stakes and deserted its namesake city). He’d just used two simultaneously recorded records — the groundbreaking synthesizer-based funk ’n’ pop slabs Music of My Mind and Where I’m Coming From — to force Gordy’s hand into inking an unprecedented contract renegotiation. By doing so, he won the financial resources and the artistic freedom to do whatever the hell he wanted.

He was 21 years old.

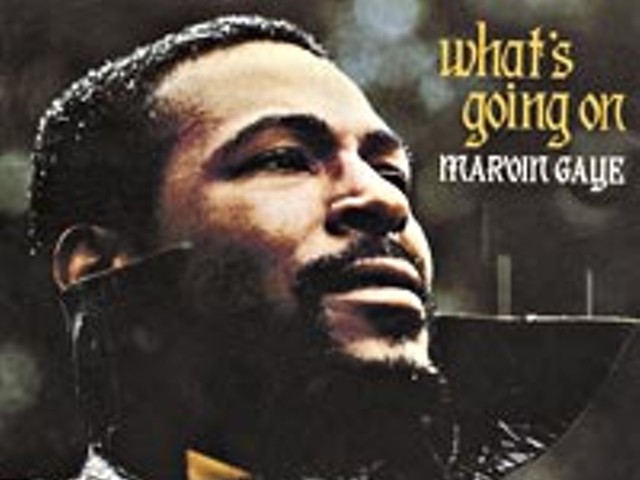

By 1973 when Innervisions hit the streets, he was splitting with his wife, muse and songwriting partner, Syreeta Wright. Nixon had come to power. Cities were smoldering. Vietnam was drawing to a painful close. Soul was the nation’s protest music of record. Wonder’s labelmate Marvin Gaye had blown the ears off the world with What’s Going On and now Wonder had gone to the mountain and come back with the nine songs that comprised Innervisions.

While Innervisions may not have been, technically, a “Detroit” record, Motown was still tapped into the sound of young America — only in a very different way than when the kids were waiting for Mr. Postman.

“Innervisions came along at the end of Motown when they were really expanding out of the parochial vision of the Detroit sound,” says Collins. “The artists were focusing on the situation at large and they had to say something about it — hence ‘Jesus Children of America.’ On one hand it’s a Detroit record, but it’s really a global record. Because it’s so politically charged. Most Detroit records are about dancing. For all the danceableness of a track like ‘Higher Ground,’ the message is more global.”

“Many have proven that you don’t have to live in Detroit to capture the feeling of the city,” says Craig.

“It’s a pretty record. The ideas are stated wonderfully, but it sonically captures the landscape of the city. Listen to Innervisions driving down Gratiot or Mack and it’s an instant urban sound track.”

Moreover, the record’s messages still resonate.

“Nothing’s changed,” laments Collins. “To be perfectly frank, it’s high time he cut another one! I played the whole album last January and it was still relevant. It’s a wonderful thing that it’s so universal, but it’s a crying shame too.”

The two hit singles alone — the gritty “Living For the City” and the self-examination-as-celebration funk of “Higher Ground” — would’ve secured the album a place in the hearts and minds of millions. But Stevie was after a grander statement about the nature of the spirit and the power of hope. He made it by stretching his compositional arms around the entire world of music. But his lyrics told unblinking testimony of contemporary urban America and its sins and salvation.

It is a fusing of the personal and the political that allowed the nuances of Innervisions to be claimed and explored by successive generations of musicians.

The profound ripple effect of its universal sonic alchemy is still felt in the four corners of the musical world — from the frat funk of the Red Hot Chili Peppers to the techno dance floor, from Public Enemy to garage rock — with some unexpected stops in between.

“In house music, his gospel-based songs have had a major impact,” says Craig. “To other electronic music I would think that [the main influence is] his use of African and Latin percussion and rhythm patterns.”

“Innervisions was, like, ‘Now that I got complete control, let’s see if you’ll put this out!’” says Collins. “Gee, do you think that’s influenced me?! Maybe that has something to do with being from this area. I just relish the fact that being a musician in this town and challenging authorities go hand in hand. We make our own rules.”

Return to the introduction for this special collection of music stories, where you'll find links to the other nine records on our list of Detroit discs that shook the world.

Chris Handyside is a freelance writer for Metro Times. Send comments to [email protected]