Walking into Riverview High School to hear a presentation by University of Michigan professor Paul Mohai and two of his colleagues last week, News Hits caught a whiff of the nauseating petrochemical stench spewing from the nearby Marathon oil refinery along I-75.

It's a truly sickening smell.

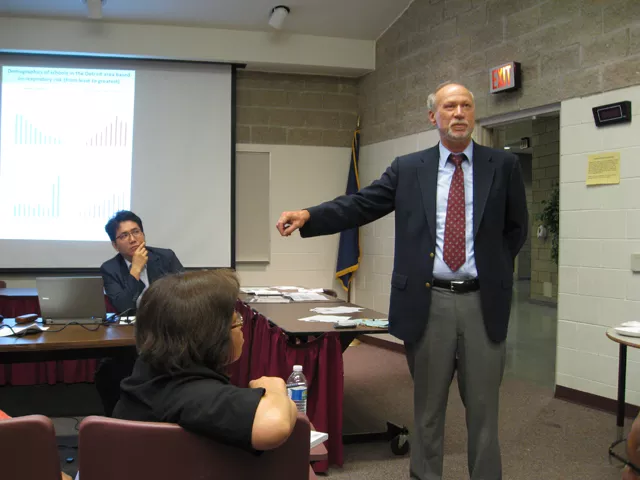

Inside the school, a steady stream of charts projected on a screen only added to the stomach churning.

The info being relayed by Mohai wasn't exactly new. Last year, the peer-reviewed journal Health Affairs published a piece written by Mohai and three others. The headline did a pretty good job of summing up what the researchers had found: "Air Pollution Around Schools Is Linked to Poorer Student Health and Academic Performance."

What the headline didn't capture is this: African-American and Hispanic students, as well as kids from low-income families, are the ones most likely to be enrolled in schools that are in close proximity to sources of pollution.

Which is why Rhonda Anderson invited Mohai and his fellow researchers — Byoung-Suk Kweon, a former U-M prof who recently took a job at the University of Maryland, and Sangyn Lee, a postdoctoral research fellow at U-M's School of Natural Resources and Environment — to Riverview to talk about their findings.

An environmental justice organizer for the Sierra Club in Detroit, Anderson says there is a dire need for decision-makers to take notice of this and similar studies, and for people in general to be aware of what's going on.

She looks back to 2009, when the Detroit Public Schools' fourth- and eighth-graders made headlines by registering the lowest performance in the history of the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests, which are used to evaluate students nationwide.

At the time, there was much finger-pointing going on. People were understandably blaming the schools, blaming the teachers. But there were also some, Anderson says, who used the poor showing to reinforce racist stereotypes.

For the bigots who want to believe that blacks are intellectually inferior to whites, those abysmal test scores in an overwhelmingly African-American school district gave them fresh ammunition to defend long-held prejudices.

Mohai's study, on the other hand, offers something much different: Evidence of a system where children of color and children of poor parents are placed at a disadvantage from the start.

Mohai, a founder of U-M's Environmental Justice Program, is careful to point out that his research doesn't prove proximity to pollution lowers academic achievement.

Scientists in general tend to be wary of declaring anything in absolute terms. That's not what they are trained to do.

What he does say is that there appears to be a strong correlation between where schools are located and how the children in them perform.

This is how he and his colleagues put it in the abstract of that paper published by Health Affairs:

"Exposing children to environmental pollutants during important times of physiological development can lead to long-lasting health problems, dysfunction and disease. The location of children's schools can increase their exposure. We examined the extent of air pollution from industrial sources around schools in Michigan to find out whether air pollution jeopardizes children's health and academic success. We found that schools in areas with higher air pollution levels had the lowest attendance rates — a potential indicator of poor health — and the highest proportions of students who failed to meet state educational testing standards."

It's a simple equation: As pollution rates rise, academic performance goes down.

What the data doesn't capture is the tragedy of so much lost potential.

It's not just children of color who are being placed at risk. During the presentation at Riverview, using PowerPoint to display an array of graphs and color-coded maps, Mohai observed that schools around the state are often located in the parts of their district with the highest levels of pollution.

He says that's because the cost of land is often the driving force when a district is looking to build a new school, and land prices go down if there are polluting factories or power plants nearby.

It is an issue that requires attention, Mohai contends.

"Half of the states, including Michigan, do not require any evaluation of the environmental quality of areas under consideration as sites for new schools, nor do they prohibit siting new industrial facilities and highways near existing schools. This makes it likely that new schools will be built in undesirable locations to keep the cost of land acquisition down," he and his colleagues noted in their study.

But what's true in general is even more pronounced for minority students and the poor.

The study found that slightly more than 44 percent of all the white children in the state attended schools in the areas of their district with the highest levels of pollution. For African-American and Hispanic students, however, the respective numbers are 81.5 and 62 percent. Likewise, 62 percent of students enrolled in free lunch programs — that is to say, poor kids — attended schools in high-pollution areas.

"Our findings underscore the need to expand the concept of environmental justice to include children as a vulnerable population. They are required to attend school, and have little or no say in where they live or go to school, which makes them particularly dependent on governmental policies to protect them from harm," the authors declare. "Moreover, as our findings show, children of color are disproportionately at risk."

The half-dozen or so people attending the presentation were from the most heavily polluted part of the metro region — the industry-heavy part of southwest Detroit, River Rouge and Ecorse.

As Anderson noted, Mohai was preaching to the choir.

They are activists who've long been engaged in a fight to make industry more accountable to the communities where they are located.

Mohai hopes that they will be able to work together in an effort to get the data and analysis in front of state and local officials so that they can use it when making decisions about where to place schools — and, also to help them decide which schools should be shuttered in districts like Detroit, where the student population continues to decline.

For Anderson, who grew up downriver, her work as an environmental justice advocate is more than just a job. It's intensely personal. At last week's presentation, she talked about what it was like to grow up surrounded by heavy industry:

"For us, normal was looking out the window and seeing an orange sky."

The quest for a new normal continues. But thanks to Mohai and his colleagues, they now have something they didn't possess before. It's not the knowledge that something wasn't right. Their eyes and lungs informed them of that.

What they have now is science, and it is clearly on their side.

"People in our communities have known that something's been wrong for a long time," says Anderson. "They've been saying it over and over for years. What's different now is that we have the data to support what we are saying."