The music of Suzanne Ciani ranges from the purely commercial in the most literal sense to abstract, futuristic, electronic art tones. In the 1970s and '80s, her company Ciani/Musica made electronic music and effects for commercials for clients like GE, Coca-Cola, and appropriately, Atari. She also collaborated with Bally to provide the futuristic bleeps and blips for their popular Xenon pinball game. Ciani's electronic music expertise can be heard embellishing schlocky '70s hits like Meco's "Star Wars" and the Starlight Vocal Band's "Afternoon Delight." But dig a little deeper into her discography, and you'll find that she contributed to albums by Bryan Ferry and Yusef Lateef, alongside her own early entries in the New Age genre.

Lately, Ciani has been celebrated as listeners rediscover her pioneering '70s work created on the Buchla, an iconoclastic electronic music instrument that was lauded as the first portable modular synth. She's hailed as an innovator in this music, alongside Daphne Oram, Delia Derbyshire, and Laurie Spiegel. Psychedelic crate digger Andy Votel has issued several records of vintage Ciani sounds on his Finders Keepers record label, including a killer, previously unreleased album of Buchla recordings made at minimalist figurehead Phill Niblock's loft in 1975. Bringing her varied and surprising career together, A Life in Waves, a feature documentary on Ciani, premiered at SXSW last month. Ciani comes to Detroit for a talk and performance on the Buchla at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

Metro Times: When you first encountered the Buchla system, what did you think of it, and how did it contrast with your musical upbringing?

Suzanne Ciani: I've always thought of myself as a composer; I was raised on the piano. We had a lovely Steinway, and I played endlessly. When I met Don Buchla in the late '60s, I became aware that a traditional keyboard approach would divert from the essence of this new instrument and new way of playing. I was attracted to the Buchla instrument as a composer primarily because I had complete control over the design of the composition. I didn't need to depend on an orchestra or other musicians. Also, I found the sound palette to be absolutely mesmerizing — to go from the very lows to the very highs off the charts. My ear rejected acoustic music for many years, because it wasn't exciting enough, it wasn't sufficient. I was attracted to the compositional aspects, and also the three-dimensionality, because we worked in quadrophonic. The audience is immersed in a surround sound, and the spatial parameters of the music are as essential as any other parameter.

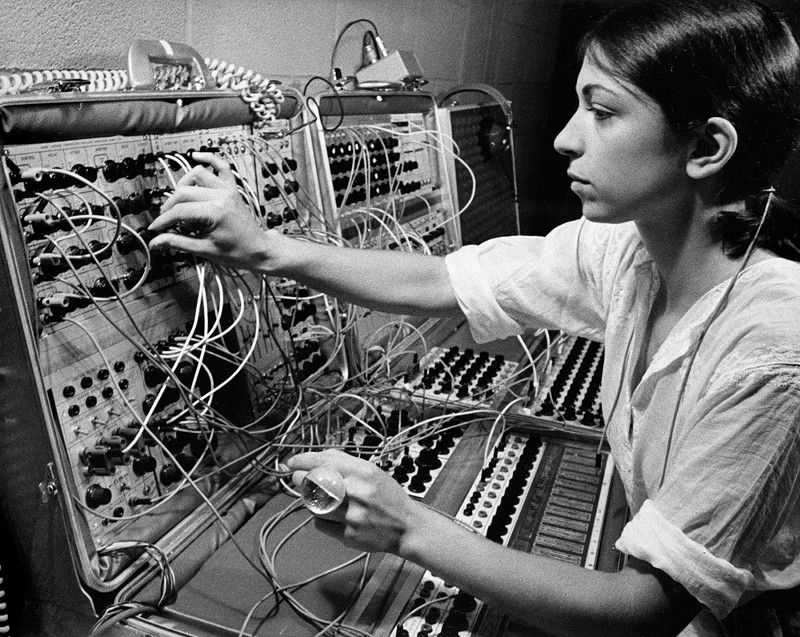

I dedicated myself, for about 10 years, to performing on that modular electronic music system. We did not use the word "synthesizer," because it had connotations. At that time, the consciousness of electronic music took a left turn when they put a mechanical keyboard on some electronic instruments, and it became more about making sounds and playing them on a keyboard. Whereas what I do with the Buchla involves no traditional keyboard. And the music is made, on the spot, using the interface, which involves knobs, dials, patch cords, and a touch plate.

MT: What are some of the advantages of using this vintage equipment, versus using a computer nowadays?

Ciani: The computer is boring. The computer is not a performance instrument. The computer uses pre-recorded sounds, most of the time. The sounds that I'm working with are created instantaneously by the electronics of the instrument — there's nothing sampled. I'm interacting in many ways, physically, with the machine; it's like a choreography. The machine has a lot of feedback, so it tells me what it's thinking and what it's doing, and signals me with lights. There are a lot of LEDs that are talking back to me so I know what's going on inside. You can have a computer performance where somebody is just sitting there and hitting "play." That's not what I'm doing. What I'm doing is a concept that was new back then: You could interact, live, with a machine, and create music in the moment.

One of the problems with electronic music performance is that people don't know what they are hearing. It's like, "Wait a minute. Was that just a playback? Was that composed in the moment? What is going on?" It's so hidden. What I do is let people see. I explain what the experience is, what it's based in. And then I give people a view. I have a camera that I put on the instrument, so that the audience can watch what's going on.

MT: How did your electronic work prepare you for your work with commercials?

Ciani: I went to New York with just my Buchla. That's all I had! I consciously figured out that I could make money in advertising. The record companies were not interested. I couldn't get a record deal. I loved working in television. They gave me complete creative freedom, because they didn't know what I was doing! We were the No. 1 sound design company in Manhattan. Any high-tech company wanted me to do something. It was perfect for advertising, because they wanted to be on the new frontier. Advertising was looking forward: "I don't know what that is, but we want it. We want to be different."

MT: Were you continuing your work in a variety of different styles?

Ciani: When I first got to New York, I was hoping to do live Buchla concerts. I ran into a lot of barriers. I had a concert scheduled at Lincoln Center, and they wouldn't let me put up four speakers! And I said I can't play unless it's in quadrophonic. None of the theaters were adaptable to this spatial music in those days. As time went on and I became more frustrated with the challenges of solo live Buchla performances, I developed an evolutionary hybrid of classical and electronic, which was Seven Waves [Ciani's first new age record from 1982].

Also, I have to say that there was a frustration with the audience, because they didn't understand Buchla. You would play live, and they wouldn't know where the sound was coming from. That's why it is such a pleasure to come out today and play to an audience that's grown up on electronic music. That's a whole new world for me, to have that audience. I love it.

Suzanne Ciani performs this Thursday, April 13, at MOCAD; doors at 7 p.m.; 4454 Woodward Ave., Detroit. mocadetroit.org; admission is $12 ($7 for members).