West of Memphis | B

How you receive the new documentary from Amy Berg (Deliver Us from Evil) depends a lot on what you already know. Those who have never heard of the West Memphis Three, a trio of Arkansas teenagers who spent nearly two decades in prison for a crime they clearly did not commit, will probably experience despair and rage in equal measure while watching this 145-minute chronicle of gross injustice. West of Memphis exposes a legal system that is manipulated by unscrupulous prosecutors and despicable lawmakers out to appease hysterical mobs and advance their careers.

For those who have seen Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s landmark Paradise Lost trilogy, however, there is the nagging feeling that this “untold story” has arrived late to the game and declared itself the winner. More a recap and appendix to the three HBO documentaries, Berg’s film is certainly provocative in its treatment, having the advantage of hindsight to construct a lucid, compelling narrative, but it’s only in its second half that it proves its worth.

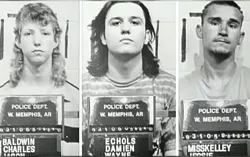

In 1993, the mutilated bodies of three young boys were found drowned in a drainage pond in the Robin Hood Hills neighborhood of West Memphis. After roughly a month of investigation three teens — Jessie Misskelley Jr., 17, Jason Baldwin, 16, and Damien Echols, 18 — were charged with the crime. Though there was no physical evidence linking them to the murders, authorities claimed they had killed the boys as part of a satanic cult ritual. This was determined by the boys’ love of heavy metal music and preference for black clothing. Misskelley, who had an IQ of 70, eventually confessed under police interrogation, though his account didn’t match the details of the crime. He and Baldwin were given life sentences, and Echols — legally an adult — was put on death row.

Berg’s film only occasionally references Berlinger and Sinofsky’s documentaries. It seems to forget that it was their films that first presented evidence of a shoddy police investigation and an unprincipled prosecution. Nevertheless, by hiring her own investigative team of legal and forensic experts, she is able to assemble a critical mass of evidence that contradicts the state’s case and provides the film with dramatic gotcha moments. This ultimately convinces the Arkansas Supreme Court to arrange a plea agreement with the three men to win them their freedom.

Where West of Memphis really hits its stride is in its inquiries into Terry Hobbs, the stepfather of one of the victims. A man with a disturbing, violent past, his alibi is convincingly called into question, and interviews with other family members reveal unsettling behavior. Berlinger and Sinofsky first hinted that Hobbs might be the likeliest suspect in their third film, but Berg seems convinced of his guilt — a troubling attitude given the miscarriage of justice her subjects endured. While the evidence is damning, if there’s one thing this movie proves, it’s that everyone deserves a fair trial.

Unfortunately, to compound Arkansas’ profound perversion of justice, not only did the state steal 18 years from the three teens’ lives and subject them to horrific abuses in its prison system, their release deal required that they agree that the prosecution had enough evidence to convict them. This legal maneuver, known as the Alford Plea, not only shields the state from lawsuits but also guarantees that the real killer will go unpunished.

West of Memphis, being able to follow up with Misskelley, Baldwin and most especially Echols, provides us with meaningful context for what these men endured, the grass roots support that sought to secure their freedom (inspired by the Paradise Lost films) and where their lives are headed next. But much of this is compromised by a troubling display of starfucking. Berg’s narrative frequently shifts to Echols’ celebrity supporters. This not only seems indulgent, it portends the September release of The Devil’s Knot, a movie to be helmed by Atom Egoyan and starring Reese Witherspoon and Colin Firth.

In the end it’s not clear why Berg’s film needed to be made. Yes, it fills in a few important gaps, corrects some mistakes, and provides context, but one can’t help but feel that the celebrities involved needed this document of their efforts to appease their vanity. As tragic and enraging as the story of the West Memphis Three is, it has to be asked: Might this support have been better spent spotlighting some lesser-known travesty of American justice rather than revisit a case that has already gained celebrity, notoriety and a Hollywood production? mt