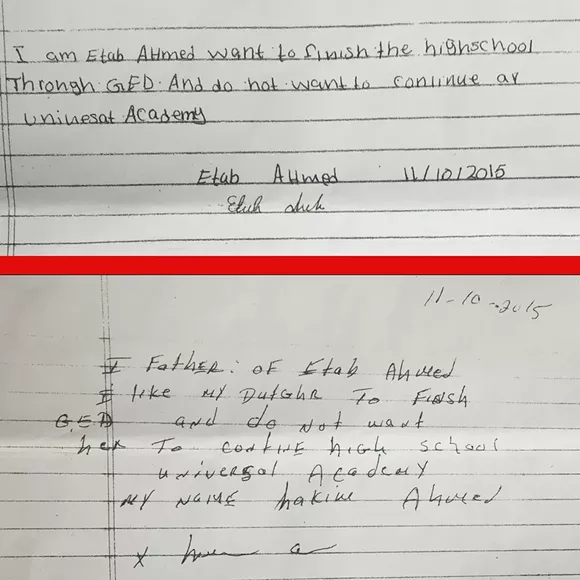

ETAB AHMED WAS staying after school to work on her math homework one unusually warm November afternoon this past fall. She, however, couldn't concentrate. Earlier that day she had been called into the principal's office, where she was asked to copy and sign a document. Etab didn't understand all the words she wrote out, but they seemed to have to do with finishing high school, and that made her giddy.

When Etab, a soft-spoken and polite 20-year-old, moved to the United States from Yemen in 2010, she struggled with school. While she knew she wasn't stupid, most days she couldn't help but feel that way; not only was Etab having a difficult time learning English, but she was two years older than the majority of her peers. After her first school, O.W. Holmes, was closed by Detroit Public Schools' emergency manager Roy Roberts in 2012, she transferred to Universal Academy, a K-12 charter school on Detroit's west side, and at 17 she was placed in the ninth grade.

Etab says that despite these obstacles, she's maintained one goal: to graduate. And this year — her senior year — it looked like the diligence was paying off. She had earned all A's on her latest progress report, and now the school's principal Uzma Anjum had called her and her dad, Hakim Ahmed, in to talk about graduation and a new word Etab had learned that day, but still didn't quite understand.

"Miss?" she turned to her teacher Asil Yassine whose classroom she was working in. "What's a GED?"

Yassine, a second-year teacher at Universal, says she was surprised by the question and explained that a GED was a high school equivalency diploma, a way for people who didn't finish high school to still get credit. "You don't need to think about that, though," she laughed.

Sitting on a plastic-covered couch in her family’s living room, Etab is shaking as she recalls what happened next; how she started crying as she told her teacher about the statement she had written out and signed hours earlier.

"I am Etab Ahmed want to finish the high school through GED. And do not want to continue at Universal Academy - Etab Ahmed 11/10/15"

Still visibly upset nearly six months later, she explains how she thought a GED was some sort of dual enrollment program; something to help her get a college and high school diploma simultaneously.

"The school is taking advantage of them because they think they don't know how to read or write and talk," family friend, Yeasser Said, who helped Etab’s dad translate the statements interjects. "For them, it's just business and money. They don't get funds for Count Day? Snap! Come sign this paper."

While Michigan’s School Aid Act says a general education student must be younger than 20 as of Sept. 1 to be eligible for state funds, the reality is, according to Casandra Ulbrich, the vice president of the state Board of Education, a high school diploma may be awarded regardless of a person's age, and a school can continue enrolling a student sans per pupil funding if it so chooses.

The school had collected the state per pupil allowance for Etab for three years — a total of more than $25,000 — and now it was pushing her out with little more than a "good luck." This, and the fact that Etab was seven months shy of graduating, disturbed her teacher, Yassine, who at the time decided to follow up.

"I am struggling to understand how this incredibly bright, hard-working student who fully deserves a diploma from Universal Academy can be removed so suddenly from her education," Yassine wrote in a Nov. 14 email to Nawal Hamadeh, the superintendent of the school and CEO of Universal Academy's management company, Hamadeh Educational Services.

"Could you please send me a copy of the federal or state law or HES board policy that describes why this student is too old to stay in school?"

Yassine says she received no response.

As she'd soon learn, this lack of transparency is a norm.

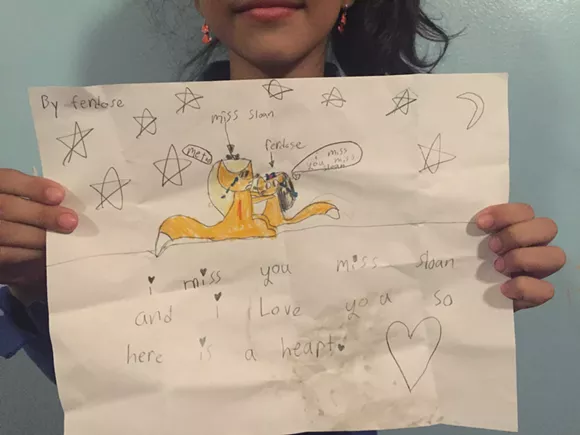

Three months later, on Feb. 12, Yassine was one of eight teachers who were fired, via email, from Universal Academy.

Just as she never received answers from Hamadeh as to why Etab was pushed out, she and the other teachers who were fired have yet to find out why they were let go. They have suspicions, sure — six of the eight teachers who were terminated attended a board meeting on Jan. 26, where they tried to draw attention to problems they believed were adversely affecting the school culture and students. But, nothing could be confirmed. Their termination letters simply reiterated that they were hired at-will and could be terminated "at any time, with or without cause, and with or without notice."

Today, substitutes and teacher's aides have assumed the roles of the missing teachers, and the issues discussed at the January board meeting — inconsistent discipline and a lack of support for English language learners — have been exacerbated, according to parents, students, and teachers interviewed by MT. As Yassine, and those within the Universal community have discovered, educators and kids can be expendable, especially when a school is manned by a for-profit management company and an appointed board, who have little to no accountability to the public.

WHILE WE'VE HEARD about teacher sick-outs, corruption indictments, and dilapidated buildings within Detroit Public Schools in recent months, there has been no news of the teachers being fired at Universal.

This is partly due to the fact that each charter school is something like a sovereign nation, and therefore difficult to monitor. It also has to do with the state's molasses-pace when it comes to enacting charter accountability reforms.

In the summer of 2014 — three years after Gov. Rick Snyder lifted Michigan's cap on charter schools — it appeared like some real changes were coming down the pipeline. In June the Detroit Free Press released a yearlong investigation into the state's lax charter laws. By August, then-State Superintendent Mike Flanagan announced that 11 charter authorizers had been placed on an "At-Risk-of Suspension" list. Come December, however, the urgency seen that summer was fading. Flanagan announced that month that he would not be going forward with his review of the authorizers; he wanted first to hear Snyder's plans for Detroit's schools.

Today the Michigan legislature is debating a number of bills largely informed by Snyder's January 2015 proposals. Charters, however, are but a small component.

One of the only charter-related measures that's been proposed is the Detroit Education Commission, an appointed board that would monitor future school openings and closings in the city, based on grades awarded to every school in the city each year.

There is a fear, however, that even this — which is still being largely protested by charter advocates — won't be enough. Under the state Senate Legislation that passed last month, the grades awarded by the DEC would based 80 percent on proficiency and growth measures and 20 percent on non-academic factors like year-to-year re-enrollment rates.

Poor school culture — environments created when families and teachers feel muted — is not a part of the equation. While charter advocates would likely insert some free-market adage here ("Parents can vote with their feet"), pointing to the 20 percent of that grade that includes re-enrollement rates, the reality is this sentiment does not always translate.

While MT spoke with a number of teachers, parents, and students who were frustrated with Universal — so much so that they kept their kids home on Count Day to stop the school from receiving state aid funds — all of them said they would not leave the school. Located in a low-income, predominantly Arab neighborhood on the border of Detroit and Dearborn, Universal — despite its presumed failings — is still a community.

As one parent of three Universal students, Consuelo Ruiz, put it: "Hamadeh came to our community, she's getting money for our kids, she needs to educate those kids."

THE TEACHERS WERE fired on a Friday evening, between 9 and 10 p.m., on the first day of winter break.

"We were all just crying, everyone just started crying and checking their email," says Phil Leslie, a second-year math teacher, who was one of the eight fired teachers. He and six of his colleagues had gone up north to Petoskey for the three-day break and were baffled when they discovered, one after another, their termination letters. Of the seven people on the trip, four were fired. "We were just trying to figure out why. Nobody could figure it out. We had a hunch that maybe it was because of the board meeting," Leslie says.

News of the firings quickly spread to students and parents. The response was so overwhelming that Hamadeh called an meeting at the school two days later. While none of the teachers were told why they were terminated, it was explained to the parents that the mass firings were due to "safety" issues. Hamadeh would not expound on this at the meeting, saying personnel information couldn't be discussed.

Suzy Itayem and her daughter, Tekwa, a senior at Universal, were in attendance.

"We thought Hamadeh, since she's the CEO, would be responsible, not just accountable, that she'd feel for the parents and the kids," Itayem explained to MT at a small gathering of frustrated parents last month. She was baffled by the argument that the teachers — many of whom her daughter adored and respected — were "safety issues". Itayem says she asked what the issues were, but was told, once again, that personnel matters were private.

While she was livid with how the school handled the situation, telling MT that she lost it when Hamadeh told parents that Sunday that they were "either with us, the administration, or with the teachers" — she didn't expect the incident to affect her personally.

Two days after the meeting, administrators pulled Tekwa out of class and interrogated her about a "recording" taken at Sunday's event. According to the student, who's the senior class president, she was told that "witnesses" saw her take video at the public meeting. The school was demanding she turn it over, she says.

Tekwa says she was baffled, explaining that she didn't have a video and that she didn't understand why having a recording would be a problem. The meeting was public, after all.

After a back-and-forth with administrators, Tekwa says she left the room, at which point Principal Anjum grabbed her by the arm. Tekwa ran outside and called her mother, who says she called the police and filed a report. Tekwa was suspended for one day.

"The only thing all those teachers that were fired had in common was many were at board meetings, they all defended themselves, and it made sense to me after I got suspended," Tekwa says. "I defended myself, and this is what happened. So I think they're using us as an example — you try to stand up and this is what happens."

Tekwa's mother, Itayem, says she's pushing back against the teacher sackings and the school's treatment of its students.

"They messed with the wrong person, maybe it's a sign from God," Itayem shakes her head as she looks across the table at Etab's father Hakim, one of the other frustated parents who has gathered at a local grocery store to discuss the school. "God is telling us to fight for the community, and that's what I am going to do."

Before leaving the market, Itayem snaps pictures of all the documents Hakim has brought showing Etab's removal from the school. She hired a lawyer after Tekwa's incident and promises Hakim that she will fight for his daughter, as well.

IN 1970, ECONOMIST Albert Hirschman published his seminal book Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, which examines how people react when a service they depend on deteriorates. According to Hirschman, people either stick around (loyalty), leave and seek out a different version of the service (exit), or they use their voice to demand changes where the service has gone awry (voice).

In a section on education, Hirschman famously, and prophetically, noted that alternative forms of education (charter schools didn't exist at the time) fall under the heading of "Exit."

While this may make sense to anyone paying attention to current charter buzz phrases (does "parents can vote with their feet" sound familiar?), the reality is early charter pioneers, like Albert Shanker, the late president of the American Federation of Teachers, took Hirschman’s warning into account and aimed to avoid his worst case scenario. Rather than let exit strategies deplete schools of people "most motivated and determined to put a fight against the deterioration" these early supporters aimed to create innovative spaces where voice was valued. They were so adamant about charter schools being open grounds for dialogue that they stressed the importance of teachers being unionized so that they would feel comfortable speaking out and trying new ideas without fear of retaliation.

"Charters were supposed to be all three [exit, voice, and loyalty] but certainly they were supposed to represent voice, they were supposed to be locally run, public spaces for discourse," says Gary Miron, a National Education Policy Center researcher whose 2002 book What's Public About Charter Schools? details the genesis of school choice in Michigan. "That has changed. Today, many charter schools operate as private spaces."

Of the 306 charter schools operating in Michigan this year — the highest number yet — only three have staffs that are organized. Add that to the fact that nearly 80 percent of Michigan's charter school operators are for-profit — Hamadeh is one of them — and a picture is painted of a system where voice and dissent can be stamped out.

More fascinating is how this has been normalized.

"What's the story? I fail to see an issue with (at-will) employees being dismissed. No federal (or) state laws were violated," Universal's hired public relations consultant, Mario Morrow, says in an email to MT when asked for an interview with Hamadeh. The CEO declined the request.

While Morrow is correct no law has been broken — as far as we can tell, the teachers still don't know why they were fired — questions remain as to how this secrecy fosters confidence and trust among other teachers, parents, and ultimately students. And most importantly, where's the accountability to ensure decisions are truly being made with students in mind?

IN LATE MARCH , Hakim found out that Etab's transcript had been updated. The three credits it said she still needed when she was pushed out in November were now completed. Itayem credits the attorney she hired for the change.

When Hakim, Itayem, and another parent, Conseulo Ruiz, gathered to discuss the news, the sentiment was bittersweet. While the transcript technically allows Etab to receive her high school diploma, what she says she also needs and wants is support from teachers and the school community. For more than six months, she's languished at home, convinced the incident meant there was something wrong with her.

"I sleep upstairs and she sleeps downstairs. Every half-hour I am up and down the stairs. I want to make sure she is OK," Hakim says, explaining how for days after leaving the school Etab wouldn't leave her bedroom.

The news that she could suddenly get her diploma was welcomed by Etab's father, but it also felt like an empty victory. The actual rewards of a complete education were missing.

The school, via Morrow, declined to comment on Etab's case or their policies for students older than 18 citing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

While her family and friends believe that the school should have allowed Etab to stay in school, their main contention is not so much with the fact that she was pushed out, but rather with the way it was happened.

"I was so afraid Etab might do something to her health," the family friend Said says. "The school flipped this family upside down, who don't know what the rules are and don't know their rights. It's a nasty way to do business, but this isn't supposed to be business, it's education."For the students still at Universal, school, for many, has become insufferable.

"My teachers have been switched, I was trying to learn every single day, but we're doing the same things and I am just confused," Jamillah Mana, an eighth-grader, said at the school's March board meeting. "When I go to the school, I feel like I am in a prison, or caged in because I don't get the education I need."

That feeling of instability and hopelessness was reiterated at the same March meeting when one of the substitutes stood to talk. "I had a breakdown because I could not take subbing. I could not control the classroom. When you keep moving teachers, the kids don't behave as well," she says.

"They need one person to behave for. When you keep switching or put in a sub, they don't behave for the sub. They need that one figure that they are good for. I just — I couldn't do it anymore."

For the part of the fired teachers, in March Michigan ACTS, the charter-organizing arm of the American Federation of Teachers Michigan, filed charges, on behalf of the teachers, with the National Labor Relations board against both Universal Academy and Hamadeh Educational Services.

The charges allege that the school and management company fired the teachers "because of their union and protected concerted activities" such as the January board meeting where they spoke up with concerns.

"We want to set a precedent for other colleagues still at Universal to continue to work in the best interest of kids by collaborating with other teachers, speaking up at board meetings, even writing emails to administration," says Yassine.

While none of the eight teachers hope to return to the school, they do want to make it a better place for their former students and colleagues. More significantly they hope their case will have reverberating effects on Michigan's charter sector at large.

"We know we're not alone," says Leslie, who has since started working at a Detroit Public School. "We want teachers at Universal Academy and other charters to know their rights. Being an "at-will" employee doesn't mean you can be freely intimidated or retaliated against."

This post has been updated to include information about the charges that have been filed with the NLRB against the school and management company.